Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership (105 page)

Authors: Conrad Black

BOOK: Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership

9Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

East Berlin continued to be walled off and there were painful and awful incidents of individuals trying to escape and being shot down by East German guards, provoking huge and emotional demonstrations on the western side of the wall, which was officially called the “Anti-Fascist, Protection Rampart.” And there were no serious efforts to restrict air and land access from the West to West Berlin. But suddenly, Cuba erupted as the most direct and highest-stakes confrontation of the entire Cold War. It was reported to Kennedy on October 16, 1962, that U-2 photographs revealed Soviet missile launchers in Cuba, and that they were more likely for offensive than defensive missiles. Kennedy was faced with the stern choice of removing the missiles by force, which would involve the exchange of fire, and possibly heavy, or even atomic, fire with the USSR; asserting some level of prohibition but signaling that an exchange could be negotiated; or simply acquiescing in the deployment of Soviet missiles in the Americas. The last was out of the question by any measurement.

A third of those at the National Security Council meetings urged an immediate aerial attack on the sites. The negatives to that were that there was a chance that the air raids would not detect and destroy all the sites, and that the remaining ones could launch a nuclear attack on the U.S. And however it went in Cuba, Khrushchev would have to reply in a place where he had the edge—most obviously, Berlin. He could also attack American missile sites close to the USSR, such as those in Turkey. There were some people present who were concerned about unannounced bombing (as at Pearl Harbor, though the circumstances were hardly comparable), and some foreign leaders were, as America’s allies often are, irresolute and full of caution. (Kennedy sent Dean Acheson to brief General de Gaulle, who assured Acheson that he did not need to look at the aerial photographs, that he would take the word of the president of the United States as he had that of his three predecessors, and promised his complete support of whatever course Kennedy followed. De Gaulle summoned the Soviet ambassador, who replied, “This will probably be war.” De Gaulle said, “I doubt it, but if it is, we will perish together. Good day, Ambassador,” and dismissed the Russian envoy.)

192

192

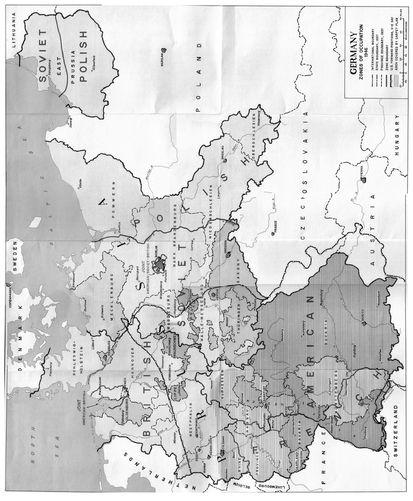

Demarcation at End of WWII in Europe. Courtesy of the U.S. Army Center of Military History

This development was particularly galling, because Gromyko had promised on behalf of his government that there would be no missile deployment in Cuba. It was decided to impose a naval quarantine on all sea traffic to Cuba, which the United States Navy certainly had the ships to enforce, and did so on October 24, two days after Kennedy sent a private message to that effect to Khrushchev and advised the nation in a clear and effective television address of the circumstances and of his action. There were four days of unsuccessful messages between Kennedy and Khrushchev, and a request from U Thant

193

that both sides undo the steps they had taken in Cuba. Khrushchev accepted to do that but Kennedy declined. After four days, on October 28, and after the U.S. had stopped and searched a Soviet vessel without incident, Khrushchev undertook to remove the missiles and have that verified by United Nations inspectors, and the United States undertook not to invade Cuba and privately agreed to withdraw the intermediate missiles from Greece and Turkey, and later claimed that, although both those countries requested that the missiles remain, the sites were obsolete and were being replaced by missiles launched from the Mediterranean by Polaris submarines.

193

that both sides undo the steps they had taken in Cuba. Khrushchev accepted to do that but Kennedy declined. After four days, on October 28, and after the U.S. had stopped and searched a Soviet vessel without incident, Khrushchev undertook to remove the missiles and have that verified by United Nations inspectors, and the United States undertook not to invade Cuba and privately agreed to withdraw the intermediate missiles from Greece and Turkey, and later claimed that, although both those countries requested that the missiles remain, the sites were obsolete and were being replaced by missiles launched from the Mediterranean by Polaris submarines.

A considerable dual myth has arisen about this celebrated and hair-raising episode. The first is that it was a great strategic victory for the United States. It certainly appeared so, as it appeared that the Russians meekly withdrew when Kennedy imposed his quarantine. But it had been a fear in the Soviet bloc that the United States, as had long been its custom in Latin America, might invade Cuba, and that option was given up. And as Khrushchev pointed out, before the crisis arose there had been American missiles in Greece and Turkey but no Soviet missiles in Cuba; and at the end of the crisis, there were no American missiles in Greece or Turkey, and continued to be no Soviet missiles in Cuba and there was an American guarantee not to invade Cuba. The explanation of the Polaris submarines is bunk; the submarines were being commissioned anyway and carried longer-range missiles, and the land-based missiles in Greece and Turkey were an added threat and were withdrawn over protests of the host countries, which weakened NATO in both countries. It was an apparent defeat for the Soviet Union but at best was, in all respects except public relations a draw for the United States. De Gaulle professed, as was his wont, to find it indicative of American untrustworthiness as defenders of Europe if the United States itself were under threat.

The second myth, and a more consequential one, was that this was a masterpiece of sophisticated and novel crisis management, based on the Critical Path method devised at Harvard University (where the president, Bundy, and much of the rest of his entourage were alumni). This held that virtually scientific calculation determined that with the application of a given amount of pressure the result was predictable. Apart from the self-serving hauteur of this fable, it was propagated on the back of another American intelligence failure: completely unknown to the CIA, the Pentagon, and the White House, there were two full Russian divisions in Cuba, and the warheads needed for the missiles were in-country, so the quarantine was, so to speak, locking the barn door after the horses had come in. While the quarantine was on, the local Soviet commander could have fired away to his heart’s content and demolished Florida, Georgia, and Alabama, at least, and the land invasion, which some of the military but very few or none of the civilians advocated, would have succeeded eventually, but crushing two divisions of the Red Army would not be like taking over the customs house of the Dominican Republic in the 1920s. Unfortunately, the theory that the Kennedy administration was on to a new level of sophisticated decision-making took hold among the putative possessors of it and led them far astray in years to come, as they wandered down the paths opened up by the president’s inaugural promise to “bear any burden ... oppose any foe,” etc. The hour of hubris was coming, soon.

What was reassuring and a great presidential accomplishment was that Kennedy, doubtless informed by the Bay of Pigs disaster, had learned a little of the skepticism about the promises of senior officers that had come so naturally to Eisenhower. Kennedy reasoned that a land invasion could be very complicated and dangerous; an air-to-ground attack on the identified sites could work but would almost certainly produce a military reaction elsewhere, probably wouldn’t take down all the launchers, and he at least wasn’t certain that the Russians had not got any missiles to Cuba. It is an academic question, as war was avoided and the Cold War ended happily for the United States and its allies eventually, but if Kennedy had attacked the missile sites by air and left it that any attack on West Berlin continued to be a casus belli as far as the West was concerned, and that missiles would, in due course, be updated and not withdrawn from Greece and Turkey, and that any further deployment of offensive weapons to Cuba would be prevented by whatever means were necessary and in the meantime the quarantine continued, he would probably have won a greater victory. But this is the perfect vision of hindsight (though some, such as Nixon, advocated it at the time), just as various more benign scenarios of Vietnam are hindsight, and even some of Korea, though they were also quite audible in 1950 to 1953. More practical and less humbling to Khrushchev would have been promising no invasion of Cuba for withdrawal and permanent nondeployment of missiles in Cuba, leaving Greece and Turkey out of it.

Kennedy did manage the crisis well, gained great stature in the country and the world, and scored some gains in the midterm elections a few days later, including the defeat of Richard Nixon in his quest for governor of California, where he very likely would have won without the tension and happy ending of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

In December 1962, Kennedy allegedly told Johnson’s successor as senate leader, Mike Mansfield, that Vietnam might be a lost cause, but that after what had been committed there already, if he now abandoned it, there would be a McCarthy-like Red Scare and he would not be reelected, but that he could pull out after he was reelected.

194

It is not certain that he believed this. If he had explained what he thought the war would cost and said that the smart move was to dodge that one and start Eisenhower’s dominoes off one country further on, such as Thailand or Malaysia, or both, the country would have bought it, especially as he could still blame the whole shambles on France, with a slight donkey-kick to Eisenhower. On the other hand, the communists were now a huge threat in Sukarno’s oil-rich but ramshackle Indonesia, the world’s seventh most populous country, which really was a big domino. The strategic decisions that awaited in Vietnam, and could not be long postponed, were very difficult.

194

It is not certain that he believed this. If he had explained what he thought the war would cost and said that the smart move was to dodge that one and start Eisenhower’s dominoes off one country further on, such as Thailand or Malaysia, or both, the country would have bought it, especially as he could still blame the whole shambles on France, with a slight donkey-kick to Eisenhower. On the other hand, the communists were now a huge threat in Sukarno’s oil-rich but ramshackle Indonesia, the world’s seventh most populous country, which really was a big domino. The strategic decisions that awaited in Vietnam, and could not be long postponed, were very difficult.

In August 1963, the Diem government in Saigon, as Henry Cabot Lodge arrived as the new ambassador, began a crackdown on Buddhist monks protesting what they claimed was Diem’s despotism. This resonated very strongly in the United States and there was widespread unease about what America was doing to assist an ally whose conduct caused pacifist Buddhist clergymen to incinerate themselves. Lodge was asked to persuade Diem and his brother to retire, and failing that, to let it be known to Diem’s generals that a coup would be in order. (A subsequent president, Nguyen Van Thieu, told the author, on October 1, 1970, that it was very difficult even to get fuel for his tanks in October 1963, so tightly had the United States clamped down on the regime.) There were contacts between faction heads and the U.S. embassy and repeated exploratory missions from Washington to Saigon to try to sort out the discrepant reports from the Defense Department, which claimed that substantial progress was being made, and the State Department, which reported that the country was being lost to the communists.

On November 1, one of Saigon’s more egregiously political generals, in intimate contact with everyone from Ho Chi Minh to the Pentagon and the State Department, effected a coup, removing Diem and his brother and murdering them both. The U.S. administration approved a coup, but not the murder, though it might reasonably have surmised that such a fate was eminently possible. Diem had been put in place by Eisenhower, Nixon had represented the United States at his inauguration, and he had been a reasonably competent president in horribly difficult times. The initial reaction in Washington was almost euphoric, and it was assumed that this would clear the way for the triumph of democracy in South Vietnam. The implications of the United States acquiescing in the overthrow and murder of the ally it had encouraged to tear up the Geneva provision for pan-Vietnam elections, and with which it professed to set up an anti-communist “partnership” within SEATO just two years before, were not confidence-building for America’s Asian allies.

It will never be known what Kennedy would have done had he been reelected to a second term; he had ordered the withdrawal of 1,000 men (out of about 16,000) from the mission in Vietnam by the end of 1963. This writer’s suspicion is that he would have found the whole proposition so uncertain, the military advice so questionable, and the political difficulties of reversing Laos neutrality and cutting the Ho Chi Minh Trail so daunting, in the world and in the country, when feeding untold tens of thousands of draftees into such a dodgy mission, that he would have made the most elegant exit he could have, and simply said that taking a stand there would have been the stupid option. This was no Quemoy and Matsu, and even there, Eisenhower had no troops on the ground. But this is conjecture. This was where things stood at the end of the Kennedy presidency.

On June 26, 1963, Kennedy spoke in West Berlin to a wildly applauding audience of over two million and uttered the famous words “Ich bin ein Berliner” (I am a citizen of Berlin), which he held, in contemplating Khrushchev’s hideous wall, to be the proudest claim a free man could make. “Freedom has many difficulties and democracy is not perfect, but we have never had to put a wall up to keep our people in.” It was a memorable speech and Kennedy’s suavity, courage, and eloquence made him very popular in the world. (As he left Berlin, he told an aide, “We will never have another day like this one, as long as we Live.”

195

He didn’t.)

195

He didn’t.)

Kennedy had taken up the torch of a nuclear-test-ban treaty, originally Stevenson’s idea, in 1956, which Eisenhower had ridiculed successfully and then exhumed in the last year of his presidency, only to have it torpedoed by Khrushchev in his histrionic reaction to the U-2 incident. They had agreed at Vienna that they should restart this process, and in July 1963 Kennedy sent the ageless Averell Harriman back to Moscow, where he had been the ambassador 20 years before, to negotiate such an agreement. By this time, newly launched American satellites had confirmed that the missile gap was nonsense and that the American position was superior. This unfortunately did not bury McNamara’s enthusiasm for allowing a complete Soviet catch-up, to make agreement easier, rather than to tempt the Russians with the prospect of outright nuclear superiority. An agreement was reached, which the U.K. but not France immediately endorsed, banning nuclear tests on the ground, in the air, or underwater, but not underground. It was a substantial achievement in restricting radioactive contamination and counts as a solid accomplishment of the administration.

Other books

Guide to Animal Behaviour by Douglas Glover

Harriet Wolf's Seventh Book of Wonders by Julianna Baggott

Getting Over Mr. Right by Chrissie Manby

The Dells by Michael Blair

Ride the Fire by Pamela Clare

The Middle of Everywhere by Mary Pipher

Vencer al Dragón by Barbara Hambly

Ashes of the Red Heifer by Shannon Baker

The Pleasures of Summer by Evie Hunter