Flight to Freedom (15 page)

My family was still in Cuba during the Bay of Pigs invasion, and it wasn't until May 1961 that my mother was able to leave with my brother and sister and me for Spain. (A younger brother and sister would be born later in exile.) My father remained on the island, fighting in the underground. In October of that year he fled the island with my grandmother and a group of men on a fourteen-foot boat. They were rescued by the U.S. Coast Guard, and we were reunited in New York a month later. Eventually we joined the growing Cuban community in Miami. My parents found jobs, we children were registered in school, and, along with both sets of grandparents, we went about the business of preparing to return to Cuba. Everyone thought the stay in the United States would be temporary.

But the exodus of Cubans to Miami continued, in

spurts and, by air and boat, for decades. Perhaps the most poignant departures took place from 1960 to 1962, through Operation Pedro Pan, a program to get children off of the island when their parents had not been granted permission to leave immediately with them. About 14,000 Cuban children fled Cuba alone. Many didn't see their parents for years and lived in foster homes and orphanages across the country. I have several friends and relatives who arrived in the United States under this program. Some came with older siblings, but others traveled alone, and it was an experience that rushed them out of childhood and into youthful responsibility.

The next big migration of Cuban exiles began in 1965, when Castro opened the port of Camarioca to anyone who wanted to leave the country. In less than a month, between October 10 and November 15, more than 6,000 fled in all manner of boats, most of them supplied by relatives already in Miami. It was a dangerous journey, but one that many had taken across the Straits of Florida before 1965 and still make now in homemade rafts, inner tubes, and tiny fishing boats.

I was almost nine years old when Camarioca opened and clearly remember how my parents desperately

searched for a boat captain who would bring my mother's sister and her children to the United States. (Her husband was a political prisoner.) Castro, however, closed the port before my aunt was able to leave. About two years later her family boarded a Freedom Flight to Miami. Started in December 1965, this airlift was made possible because of negotiations between the U.S. and Cuban governments after the closing of Camarioca. By the time the twice-a-day flights ended in April 1973, more than 260,560 refugees like Yara GarcÃa and my aunt had come to the United States.

The exiles' presence changed Miami. The same year the Freedom Flights stopped, the county commission proclaimed Dade a bilingual and bicultural county, and Maurice Ferre, born in Puerto Rico, became Miami's first Latin mayor. Though migration from the island slowed in the late 1970s, the United States and Cuba opened Diplomatic Interests Sections in each other's capitals in 1977. In 1978 the Cuban government also began talking with Cuban exiles to negotiate the release of political prisoners. By November 1979, 3,900 political prisoners had been freed. Most settled in Miami, among them my uncle,

who was able to be reunited with his family after serving almost twenty years in prison.

Charter flights bearing exiles back to the island also began in January 1979, the first time refugees could visit their homeland since 1961. Though I have never been back, several of my relatives have, including my younger sister born in the United States. This ability to travel to and from the island, however, did little to stop the migration of Cubans who wanted to leave for a better life in the United States. In April 1980, after 10,000 Cubans hoping for freedom flooded the embassy of Peru in Havana, Castro opened the port of Mariel to any exiles who wanted to rescue relatives. Like the Camarioca boat lift fifteen years earlier, but on a much larger scale, exiles' boats and yachts invaded the Cuban coastline. When Mariel closed in September, more than 120,000 refugees had left the island. As many as 100,000 settled in Miami, including one of my great aunts and several of my cousins.

With each wave of refugees, Miami became increasingly Hispanic. Cuban political power grew. During and after the Mariel boat lift, Hispanics constituted a majority on the Miami City Commission, and the

1980s witnessed many political firsts as Cuban-born politicians were elected mayors, school board representatives, and county commissioners. At that time several cities in south FloridaâHialeah, Miami, and Miami Beachâalready had or were close to having a Hispanic majority.

One of the most recentâand most dangerousâexoduses from Cuba occurred during the summer of 1994, when tens of thousands of Cubans took to the sea in all manner of floating devices. During a thirty-seven-day period, about 32,000 survived the journey across the Straits of Florida, but countless others died at sea. Many rafts, floating like corks adrift in the large ocean, were found eerily empty by the U.S. Coast Guard and private Brothers to the Rescue planes. Although the United States continues to welcome Cubans fleeing the Castro regime, its immigration laws are stricter now, and many Cubans who have recently attempted to flee to this country have been deported back to the island.

Exiles who, like Yara's father and my own family, expected to return to their homeland in a few months ended up making Miami home. Many who had relocated to cities in the north in the 1960s and 1970sâ

as had my uncles, aunts, and cousinsâeventually returned to the warmer climate of Florida. With freedom on our side, we built hospitals, shopping centers, schools, and housing developments. We went on to become teachers, doctors, lawyers, mechanics, developers, politicians, journalists, actresses, and beauty pageant queens.

Now, more than forty years after the first wave of Cubans to the United States, in an act of gratitude the exile community is raising funds for a complete multi-million-dollar transformation of El Refugioâthe downtown Freedom Tower that housed the Cuban Refugee Emergency Center, where about 450,000 exiles, like Yara's family and my own, received generous emergency help from the U.S. government from 1962 to 1974. The Freedom Tower will serve as an interactive museum, research center, and library chronicling the Cuban exile experience in south Florida.

I would like to thank Luis Orta and Guillermo “Willy” Aguilar for their many stories of Cuba, particularly those they shared with me about

La Escuela al Campo.

Thank you also to Carolina Hospital for her advice and to my parents, Sira and Antonio Veciana, who refreshened my memory of our early years in this wonderful country.

FLIGHT TO FREEDOM

by Ana Veciana-Suarez

Characters

1. Yara is trying to adjust to American life but is torn over obeying her parents' Cuban “rules.” In what ways does Yara respect her parents' wishes, even when she doesn't want to? In what ways does Yara decide what is best for her instead of obeying her parents?

2. Papi, Yara's father, seems to strongly resist change by repeating that the family should not adjust because they will be back in Cuba soon. At what moments do you start to see Papi adjusting to American life? Do you think that he will ever fully adjust? Explain.

3. Mami, Yara's mother, begins to adjust to the change of living in America. How does her getting a job and learning to drive a car affect the family? In what ways does Mami try to keep their Cuban heritage and customs constant in their life? How does Mami's acceptance of American life help the rest of the family adjust?

4. Ileana, Yara's older sister, tries to adapt to American life by rejecting Cuban customs. How does Ileana's rebellion affect the family? How does it affect Yara? Ileana also fights her family to get a job. How does this new responsibility change Ileana?

5. Yara meets and befriends a girl in school named Jane. How does Jane help Yara adjust to American life? In what ways do Jane and her family show respect to Yara's family's beliefs and customs?

6. Yara's uncle and his family help the Garcias get adjusted to American life. What qualities does EfraÃn demonstrate that help ease this adjustment? How does Efrain's joining the army affect the family?

7. Yara's grandfather, Abuelo Tony, teaches her and her sister, Ana Maria, many things. Abuelo Tony has many sayings. How do they affect Yara? How does Abuelo Tony's death affect the family? How does it affect Yara personally?

8. Pepito, Yara's older brother, stayed in Cuba because he was in the army. In what ways does his being in Cuba put a strain on the family? In what ways does it hold back their progress in adjusting to American life?

Settings and Theme

1. In what ways has the family's attitude toward one another changed from Cuba to America? What things have some of the family members done in America that they may never have thought of doing when living in Cuba?

2. Papi asks the family to live “suspended in the middle between two countries.” Yara disagrees and says that “we have to be either here or thereâ¦We must choose.” Is there a way to live in both? How does the family begin to accomplish this?

3. Describe some of the prejudices or other barriers the GarcÃa family faces in Cuba. Describe the prejudices or barriers they face in America. How does the family overcome them? How does Yara personally deal with them?

4. This book was written from Yara's point of view. How might the book differ if written by another family member?

5. Yara says, “It made me wonder what kind of life I might have had, the kind of life

all

my family would have had, if the Communists had not taken over our countryâ¦How strange that one event, one decision, can change so many parts of so many people's lives.” How do you think the story would have been different if the family hadn't been forced to leave Cuba?

Discussion guide written by Katy Stangland.

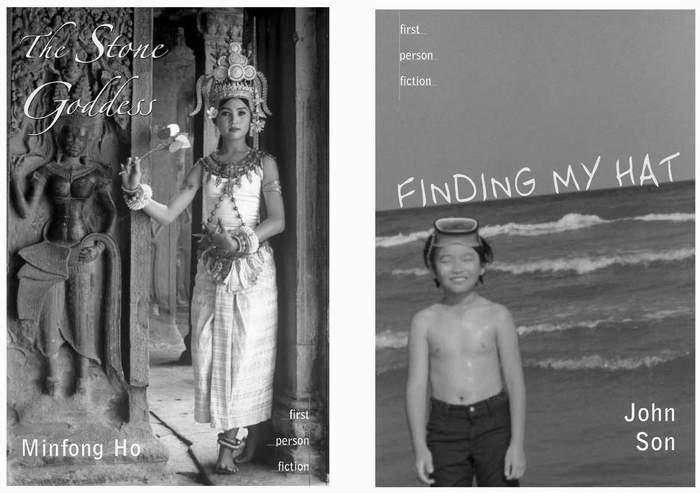

Here's a peek at the two newest First Person Fiction books,

The Stone Goddess

by Minfong Ho, and

Finding My Hat

by John Son.

By Minfong Ho

When the Communists take over the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh, Nakri Sokha and her family's life is suddenly disrupted. Forced to evacuate the city, she and her siblings are soon torn from their parents to work in a labor camp in the countryside.

Minfong Ho, the author of

The Clay Marble

and of the Caldecott Honor book

Hush!: A Thai Lullaby,

is a sensitive and powerful storyteller. With imagery that is at once vibrant and subtle, Ms. Ho shows how a young girlâthrough her love of classical danceâeventually comes to terms with a world shattered by upheavals beyond her control.

The Stone Goddess

:

Part One

W

e moved as one, the trees, the river, even the clouds in the sky were stirred by the same silent force that was moving us as we danced. It was as if all motion was guided by the same rhythm, so that we were all part of each other, inseparable yet distinct.

We had been dancing for hours, going through the strict steps that we practiced each day in the palace's airy dance pavilion. Fingers flexed far back, wrist circling continuously, back arched, shoulders straight, ankles bent, feet alternately flat on the floor or liftingâevery movement had to be controlled, and in perfect unison with the other dancers. It was late in the afternoon, and I should have been tired. But just then, a gust of wind stirred the still hot air, and suddenly I felt itâthis strong sense that everything that moved was moving with that same silent rhythm.

As I danced, I looked around me. In the distance the avenue of grand old trees in the palace gardenâthe rain trees and the jacarandas and the casuarinasâwere dipping their branches and rustling in unison, stirred by the breeze. Above them a few wisps of gray clouds sailed across the blue sky, reflected on the glistening surface of the Mekong River flowing just outside the palace walls. And as they moved, so I moved, because in dance we were moved by the same rhythm that moves the whole world.

Teeda was lifting one slim arm up, and so I did too, trained as I had been for years to dance behind my sister, following her every gesture, trying to be as graceful and natural as she was in her movements.

Like a goddess she was, like the apsaras of old that we were supposed to be, her gestures so precise and graceful that one flowed naturally into another. It looked so effortless, these subtle dance movements, and yet I knew it took years of disciplined training to do properly.

I felt a firm hand behind my shoulder, straightening it. Without turning I knew it was the dance teacher. I let her realign my arms too, and tried to keep that precise stance locked in my mind, while she moved back to correct the dancer behind me.

Then the teacher clapped her hands sharply, twice, signaling the end of the training session. The group of some fifty girls relaxed and started to disperse. As the dance teacher passed by, she reached out and touched my shoulder, so lightly it was barely a pat, but for that instant, she was not my teacher but my mother again. I smiled, knowing that Mother had noticed how well I had danced just now.

We were the lucky ones, I thought, Teeda and I, to have our own mother as our dance teacher. Our lessons would continue even after we left the palace grounds. Mother made us rehearse at home too, deftly tapping or twisting our stances closer to perfection. At this rate, I knew that Teeda would soon realize her dream. Some moonlit evening, she would be sewn into shimmering brocades, and as the musicians played on their flutes and drums and bamboo xylophones, she would perform the part of an

apsara,

a celestial dancer, before a rapt audience.

Quietly now, we waited until the last dancers had filed out of the pavilion, and then Teeda, my mother, and I slipped into our sandals and walked out down the steps into the garden, then through a side gate of the palace walls back into the outside world.

The street outside seemed even more crowded and bustling than usual. Cars, buses, trishaws, and bicycles churned past, as people hurried along the sidewalks, weaving their way around the baskets of fruits and flowers set out by the street vendors.

A basket of lotus blossoms caught my eye, their pale pink a reflection of the twilight sky.

“Let's buy some!” I said, tugging at my mother. “We need some as temple offerings for the New Year.” I could sense my mother weakening. As flowers sacred to Buddhism, we had always been taught that because the lotus had its roots in the mud, grew through the murky water, and blossomed in the open air, each lotus was like the human spirit.

“And we could use them to practice our apsara dance movements with you at home,” Teeda added.

Relenting, our mother selected the freshest bouquet of lotuses, and hurriedly paid for them.

“You didn't bargain,” I said, surprised.

“I want to get home before dark!” she snapped.

The shadows were lengthening as we turned down the little side street that led to our house. When we arrived at our wooden gate, I was surprised that it was latched. I jiggled it, but it wouldn't open.

“It's locked,” my father said, appearing behind it with my little brother, Yann. They must have been waiting for us, I realized. He unlocked a padlock around the latch.

“Pa! You're home so early,” Teeda said. “Is something wrong?” He ignored the question, and ushered us inside, before locking the gate again.

“And why the lock?” I asked.

“Hush!” Ma said. “Just to be safe, that's all!”

But I did not feel safe. That night, I heard the sound of bombs falling again. Closer they were, and clearer than I had ever heard them, all through the night and into the morning.

At dawn, I was startled by a loud crashing sound. Was it thunder, or bombs? I tried to rouse myself; Teeda had said we should roll under the bed for cover if the bombs dropped really close by. Should I do that now? The explosions continued, on and on, and I imagined our house blowing up, collapsing around me. I jerked awake, breathing hard.

By John Son

Jin-Han Park's story opens with his first memory: losing his hat to the wind on a blustery Chicago street. Though he never gets the hat back, Jin-Han, like his family searching for their place in America, never stops looking for other hats to try on. Creative, fragile, and funny, Jin-Han is a perceptive, observant narrator.

Debut novelist John Son chronicles Jin-Han's and the Park family's travels from city to city, through triumph, humor, and tragedy, as they search for a better life and a little more money. In a series of fluid, memorable vignettes laced with Korean words and timeless themes, Son builds a rich canvas, revealing a life at once unique and indistinguishable from any other.

An excerpt from

Finding My Hat

:

MY

HAT

The sudden silence of the street we'd turned onto,

Uhmmah'

s gloved hand tightening around mine.

It's the first thing I rememberâtwo years old, huffing along on short, stubby legs, trying to keep up with Uhmmah's heels clicking against the pavement. Empty paper cups skittered along the curb, sheets of newspaper fluttered around parking meters. Steel and concrete buildings shot up into blue sky. A gust of wind sweeping down the street left us shivering into our scarves, dust and grit needling our eyes. Suddenly my head felt lighter, and I blinked up to see my hat rising above us. “Oh!” cried Uhmmah, throwing her hand up after it, but the little brown acorn top she'd knitted was already out of reach. Our necks bent back, we watched it climb higher and higher, quickly a small dot, then gone over a distant roof. We gaped at the empty space where it had vanished, as if someone might throw it back. When no one did, I turned to Uhmmah to see what I should do. She looked down at me and raised her brows with a smile. I raised my brows, too, but my mouth stayed “Oh!”

“It's gone!” she said, her dark brown eyes as wide as the “Oh!” of my mouth, and then she shook her head and laughed until she noticed I wasn't laughing with her. She leaned down to tighten my scarf and kissed her nose to mine. “Don't worry,” she said. “I'll get you another one.”

And she would. I've got all these embarrassing pictures to prove it. Bright red cowboy hats, things with puffy white pom-poms on top, caps with earflaps. Early on you could see the importance headgear would play in my life.

“Uhmmah?”

We were sitting at the dining table. I was chopping onions in the onion chopper while Uhmmah got ready to make mandu.

“Mmm?”

“I think I want to quit piano.”

She stopped pinching the dumpling she was closing. “Moh rah gooh? After all the time and money we put into it?”

“I know,” I said. “But I want to stop now. I'm tired of doing it. I don't want to do it anymore.”

“But why do you want to stop now? We've spent all that money on lessons. I work six days a week to send you and Jin-Soo to a good school. My feet are always sore. My back aches. I'm becoming an old woman too soon. You need to go to a good school and make lots of money so that I can stop working. It was your idea to start taking lessons, anyway, remember?”

“But I was too young then!” I said. “I didn't know what I was talking about.”

“Aigoo,” she said, shaking her head. She finished closing her mandu and set it on the tray of mandu that was ready to be boiled. She started on another one. “Are you finished with that yet?” I opened the onion chopper and showed her. She took it from me and spooned out the onions and kneaded it into the pork that went into the mandu.

“Okay?” I said.

“Be quiet!” she said. “Don't talk such nonsense.”

“Uhmmah!” I said. “God!” And made a frustrated sound and rolled my eyes as I got up and went to my room.

I fell back onto my bed and picked up the latest book I was reading,

The Catcher in the Rye.

I'd seen an older kid at church reading it while Father Kolba went on with his usual somethings. If he thought it was worth getting caught reading it in church, I had to check it out. I wasn't halfway through it yet but I already felt the cold of New York like I'd lived there all my life. And though I didn't understand what exactly the narrator was so upset about, because every other word was a swear word, I

felt

like I knew what he was going through. It was partly why I wanted to quit piano lessons. I'd been doing it for almost eight years and hated having to practice every night. It meant more to Uhmmah than to me. I felt like it was one of the reasons why I'd chickened out with Lucinda. If I did regular things like other kids did, maybe I would've asked her out. Maybe Uhmmah would've understood how American kids went on dates and dropped us off at the movies, and in the middle of a big love scene I would've leaned over and kissed Lucinda like I could only imagine doing. Instead, I spent my days after school in the back of a wig store. Something nobody understood when I told them that was what my parents didâowned a wig store. Where finally, after years of thinking about it in the back of my mind, I took a bald mannequin head in my hands one day, wiped off her lips, and gently, slowly, practiced for the real thing.