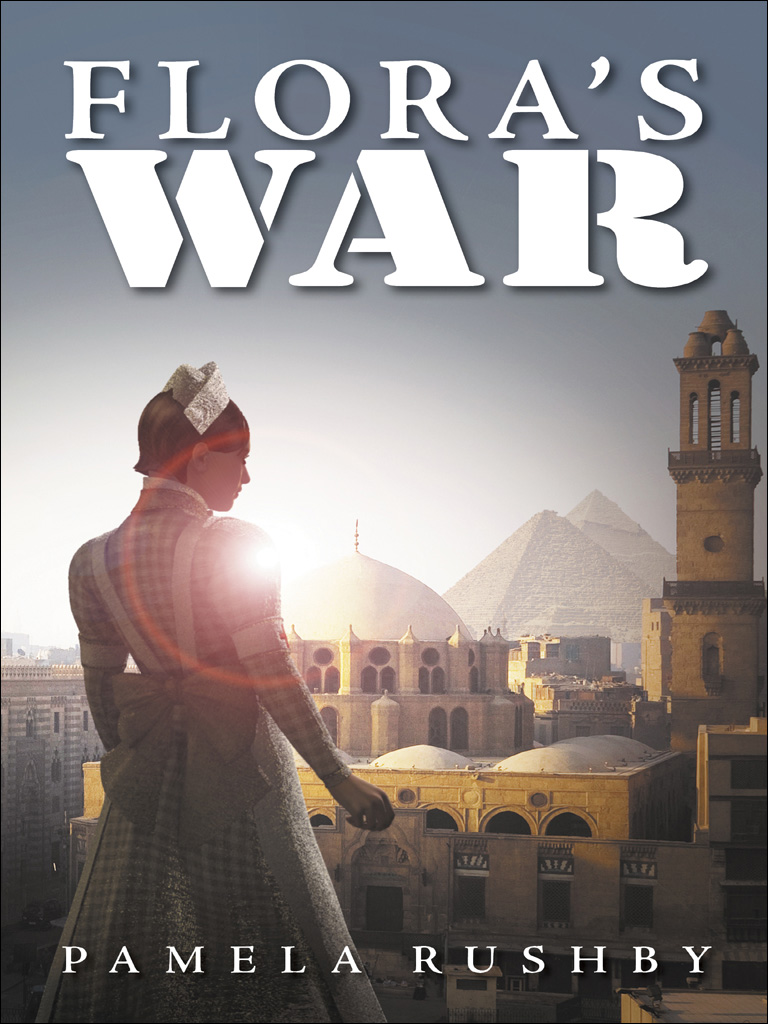

Flora's War

Authors: Pamela Rushby

Tags: #Children's Books, #Growing Up & Facts of Life, #Friendship; Social Skills & School Life, #Girls & Women, #Literature & Fiction, #Historical Fiction, #Children's eBooks

- Title Page

- About the Author

- Copyright

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Author’s note

- Bibliography

FLORA’S WAR

Pamela Rushby

Flora’s War

Pamela Rushby is a writer for children, and a producer of educational television, audio and multimedia. She has written over 150 fiction and non-fiction books including

When the Hipchicks Went to War

and

The Horses Didn’t Come Home

.

Pam lives in Brisbane with her husband, son and six visiting scrub turkeys, that peck at the back door for handouts. She has two children (plus son-in-law and two gorgeous grandchildren).

Pam is passionately interested in children’s books and television, ancient history and Middle Eastern food. Her website is www.pamelarushby.com

First published by Ford Street Publishing, an imprint of Hybrid

Publishers, PO Box 52, Ormond VIC 3204

Melbourne Victoria Australia

© Pamela Rushby 2013

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This publication is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the publisher. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction should be addressed to Ford Street Publishing Pty Ltd, 2 Ford Street, Clifton

Hill VIC 3068.

www.fordstreetpublishing.com

First published 2013

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Rushby, Pamela, 1947–

eSBN: 9781925000306

ISBN: 9781921665981 (pbk.)

For secondary school age

Book cover by Grant Gittus

In-house editor Gemma Dean-Furlong

Printing and quality control in China by Tingleman Pty Ltd

This book was partially researched as part of a Creative Time

Residential Fellowship provided by the May Gibbs Children’s

Literature Trust.

Chapter 1

Cairo, 1915

We can always smell them before we see them.

Today it’s bad, really bad, but not as bad as the first time, because then we had no conception of just what we’d see when the wooden doors of the train slid back. Then, that first time, we’d all surged eagerly forward as soon as the train stopped, ready to help, prepared to assist those who could walk and carry those who couldn’t.

And then it hit us.

It was overpowering. It stopped us dead in our rush forward; made us stagger back. It wasn’t heat, or dust, or blowing sand – in Egypt, we were used to those – but a

smell

. It was more than a smell. It was a stench. So strong it grabbed deep into our throats; made us cough and choke, made our eyes pour water. I’d never smelled anything like it before; couldn’t begin to think what it was.

I know now. It’s the smell of infected wounds, of bandages that haven’t been attended to for days, of unwashed bodies, of stale sweat. Awful. Just awful. But now, I can cope. I’m expecting it. I don’t react the way I did that first time, almost vomiting onto the sand.

Gwen did. Well, she didn’t actually

vomit.

Gwen would never do anything so unattractive in public. But she went – very prettily – quite white, and Frank had to take her back to the motorcar she was driving and sit her down for a bit. She recovered quickly, though. Gwen’s tougher than she looks, and when it’s an emergency she comes through. And she’s used to it now, after months of volunteer driving.

So am I.

Now I can step forward and say briskly to the doctors and orderlies on the train, ‘I’ve got room for three in my car, who should I take first?’ And I can smile at the white, exhausted faces of the soldiers they send towards me, and say cheerfully, ‘Hello! I’m Flora. Come on now, we’ll have you at the hospital in just a couple of minutes.’

And if one of them is not too exhausted, or in too much pain, and says something like, ‘But you’re an Australian girl, aren’t you? And you’re driving a motorcar!’ I can answer something bright and cheerful, like, ‘Well,

you

can’t be too bad then, if you can notice things like that! That’s good! You’ll be fine in no time!’

And I keep chatting and smiling, smiling and chatting, until I hand them over to the hospital staff on the wide marble steps of the hospital, steps that were once pure white and wiped down every time a foot put a mark on them, but that are now dusty and sandy and stained with the brown marks of old blood. No one has time to bother with washing marble steps now.

And then, as I turn the motorcar around and head back to the train for another load of soldiers, I can stop smiling for a moment. But then there’s another load. And another. And I have to smile again, smiling all the time, holding my breath to try to keep the appalling smell out of my throat, but never, never letting the soldiers see it.

It’s only afterwards, when the train is empty, that I can cry.

…

I’d known things were going to be different in Egypt, that season of 1914 to 1915, even well before the war began. On a purely personal level, I’d been looking forward to the season for years. This season, I was sixteen years old. A very significant age. I’d be officially grown up. I wouldn’t be just a schoolgirl tagging along to Egypt with her archaeologist father anymore, but a properly grown-up, left-school-forever young woman, who was now his assistant.

Since I turned sixteen just a few months ago, my whole appearance had changed. It was like magic, I’d been transformed from a gawky duckling into – well, if not quite a

swan

, then something as nearly approaching a swan as hairdressers and dressmakers could make me, given the raw material they had to work with. My Aunt Helen had seen to all of that.

From a plait down my back, my hair had been cut and curled into a knot on the back of my neck, with a few careless, casual, wispy tendrils (that took a great deal of work to create) around my face.

I’d had new clothes made, quite different clothes. Some of that was good, no more black stockings and skirts well above my ankles; boring, schoolgirl outfits. Now I had smart blouses and skirts that came right down to my stylish new shoes, and pretty dresses for afternoons and evenings. Wonderful! But some of it was, well, not quite so good.

‘Now you’re sixteen and you’re not a schoolgirl anymore, Flora …’ Aunt Helen had begun.

We were in a big department store in Brisbane, shopping for my new wardrobe, and Aunt Helen, who bore a bosom like a battleship, had already ploughed her way through the departments of Gowns, Millinery and Ladies’ Boots and Shoes, leaving shop assistants bobbing in her wake.

‘Yes?’ I’d said warily.

‘A corset,’ decreed Aunt Helen. ‘It’s high time you had a proper corset.’

And in the Corsetry Department I’d been inserted into a contraption of stiffened cotton and boning by a determined and formidable fitter, herself with a bosom that you could balance a tea tray on. I’d been laced up until I was gasping like a floundered fish.

I’d brought the corset with me on the ship to Egypt, but it was packed deep in my trunk. If Aunt Helen thought I was going wrap myself in that instrument of torture every day, she was wrong. It wasn’t at all the sort of garment that lent itself to crawling through narrow passages in ancient tombs and temples.

But far, far more than my newly grown-up status was making Egypt different this year. Months ago, my father had received a letter.

‘Khalid says there are very few archaeologists travelling to Egypt for the season this year,’ he said, the letter in one hand and a buttered breakfast muffin in the other. ‘The English aren’t going. The Germans aren’t going. No French, either. He wants to know what I want to do. Will I be going? What does he mean they’re not going? I can’t understand it!’

‘The war, Fa,’ I said. ‘They’re not going because of the war.’

‘The war?’ My father looked up vaguely, as if it was the first he’d heard of it. ‘Why would that stop them?’

‘I suppose it could be difficult,’ I said. ‘Awkward, you know, with English and Germans excavating next to each other.’

‘Oh.’ He thought about that. ‘I don’t see what the war’s got to do with archaeology,’ he said at last.

Well, he wouldn’t. My father hardly recognised the modern world existed. He lived, breathed and thought about little other than ancient Egypt. It was extremely fortunate for my father that his grandfather had made a fortune as a grazier. Fa could indulge his passion for archaeology without having to bother about anything as mundane as earning a living. My mother had died before I could even remember her, so my father had only himself to please. From around November to March or April every year he went to Egypt and excavated ancient tombs and temples. He donated most of his significant finds to the Egyptian Museum. Some very important pieces went to the British Museum in London. But there were plenty of other, smaller artefacts that he was able to keep. He came home to Australia, accompanied by crates of artefacts, and studied them and arranged them and wrote about them and discussed them with people at museums. In Egypt, he was as happy as a rather sandy wombat, scrabbling away under the ground.

‘You won’t be breaking any new wartime regulations by going? Mr Khalid will be able to arrange it all, won’t he?’ I asked.

I wanted to go too. Archaeology was fascinating, but the social life in Cairo during the season was absolutely glittering. And this year, I’d be able to go to all the parties and dances and dinners. I wouldn’t have to stay meekly at home like a good girl while my father went out. This year, my biggest excitement would be staying up for dinner when he had guests himself.

‘Laws? Regulations? Khalid will take care of them.’ My father brushed my worries aside like slightly annoying flies.

I nodded. I was sure he could. Mr Khalid could take care of anything.

We were going to Egypt. Just as we did every year.

As our ship approached the docks at Alexandria I began to see just how different it would be this year. There were many more ships in the harbour than usual, and they weren’t at all like the ships that usually docked here. These were sleek, grey, dangerous-looking ships, battleships, war-ships, troop-ships. The usual dockworkers, in cotton gallibayahs, dealt languidly with boxes and trunks, but there were far more soldiers. And, unlike the dockworkers, they were moving with speed and purpose. The docks and the streets just beyond were full of them, khaki ants seething around a disturbed ant nest.

Mr Khalid always met us at Alexandria, and he was easy to see, a mountain of a man, wearing a spotless white gallibayah (I’d never seen a speck of dirt or a drop of sweat on him, and I’d often wondered how he managed it) and a red fez with a tassel. He always had workers around him, ready to transfer our luggage onto the train for Cairo. I scanned the docks, but I couldn’t see him. This was most unusual.