Flying to the Moon (10 page)

Read Flying to the Moon Online

Authors: Michael Collins

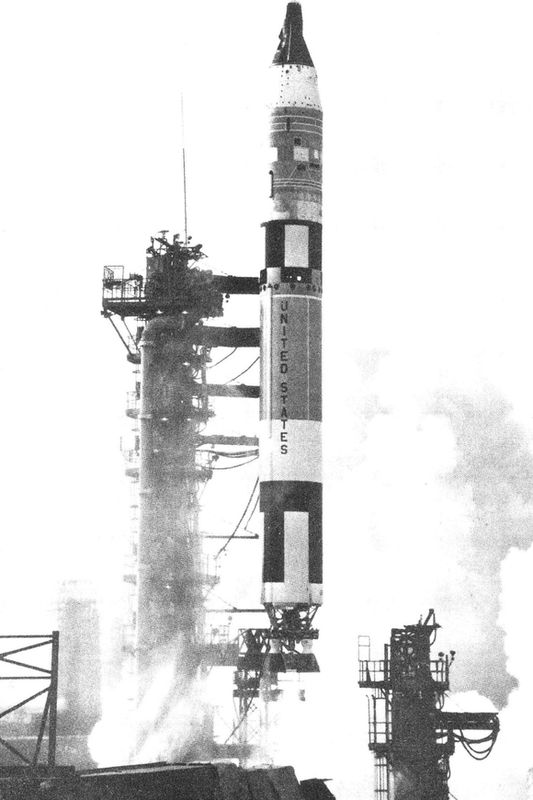

Gemini 10 departs. Shake, rattle, and roll!

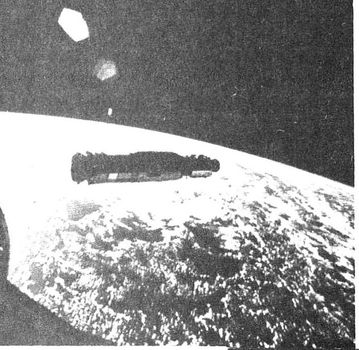

We get our first look at our Agena target vehicle

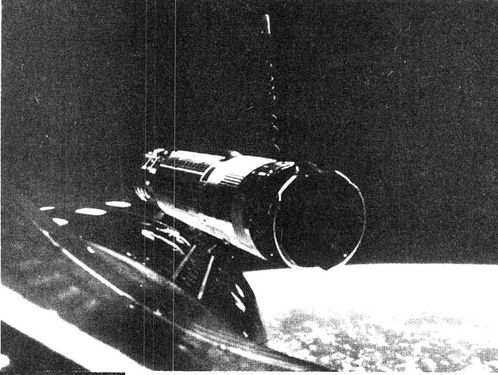

â¦and closer yet

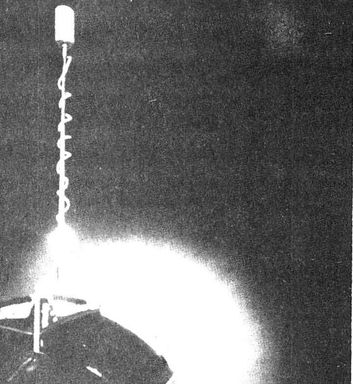

We light the Agena's engine, and it kicks like a mule

I rose slowly in the cockpit. As my left boot reached the top of the instrument panel, it snagged briefly on something, and I began a slow face-down pitching motion. Just as a diver wants to hit the water head-first, not flat on his back, so did I wish not to splat into the Agena back-first, so I had some quick work to do with the gun. After a bit of squirting, I got myself pointed back in the right direction, but in the process I found I was causing myself to rise up above the end of the Agena, which was fast approaching. As it went by, I was barely able to reach my left arm down and snag it. As my body swung around the end of it, I plunged my right hand down underneath the docking collar and found some wires to hang on to. I wasn't going to fall off an Agena ever again! Now I repeated my earlier hand-over-hand trip around the end of the Agena, heading for the experiment package. But this time I clung to wires all the way, and was able to stop my motion when I got there, rocking back and forth a few times before I got myself steadied. Again the loose piece of metal appeared to block my path, and John voiced his concern about it: “Don't get tangled up in that thing!” Fortunately, I didn't, and I was able to pull the experiment package free easily with one hand. Then it was time to get back to the Gemini. I decided not to use the gun, but simply to come in by pulling hand-over-hand on the umbilical. That was all right, provided I didn't get going too fast, because I had no way to slow down, and I didn't want to splat up against the side of the Gemini too violently. One gentle tug and I was on my way, although I didn't move in a straight line but swung in a great circle around the side and rear of the Gemini and eventually reached the cockpit and handed the experiment

package in to John. Then I made a sad discovery. I had lost my camera. It had been attached to my chestpack but had worked its way loose and was now out there somewhere in its own orbit. A couple of times during my space walk I had slowed down long enough to take a picture or two, and I knew I had some great ones, but now they were gone forever.

package in to John. Then I made a sad discovery. I had lost my camera. It had been attached to my chestpack but had worked its way loose and was now out there somewhere in its own orbit. A couple of times during my space walk I had slowed down long enough to take a picture or two, and I knew I had some great ones, but now they were gone forever.

Next on our schedule was a practice test of the gun, to see how accurately I could use it. The ground called up, however, and said we didn't have enough fuel left to do that, and for me to come back inside the Gemini and lock the hatch. As I stood in the open hatch, gathering up all fifty feet of the umbilical line, I had a brief moment to rest and to look around. I felt fine; the only part of me that felt tired was my fingers, which had gotten quite a workout inside those bulky pressurized gloves. I also realized with a start that the earth was down there! I hadn't even noticed it during the time I had been outside, having been completely preoccupied with the Gemini and the Agena. My problem now was the umbilical line. Fifty feet of heavy hose, containing oxygen tubes and radio wires, is quite a bundle. In addition to its bulk was the distressing awareness that several loops of it were wound around my body. With John pulling, and me backing out of the cockpit a couple of times, we got rid of all but one last persistent loop. This was something I had never practiced in the zero G airplane, the matter of getting snarled in the umbilical, and I didn't like to think about what it meant when I tried to squeeze down far enough to get that hatch closed. I looked down inside the cockpit and could barely make out John's shoulder. Loops of umbilical were everywhere!

Well, now was the time to find out. I wedged my body down through the nearly solid sea of coils, forcing my legs deep into the cockpit and jackknifing my knees so that my upper body swung downward and inward. I grabbed the hatch above me and pulled it inward. I knew it was going to hit either the hatch frame or my helmet. If hatch frame, fine, but if helmet, that meant I wasn't down far enough, and I would have to go back outside and try again.

Well, now was the time to find out. I wedged my body down through the nearly solid sea of coils, forcing my legs deep into the cockpit and jackknifing my knees so that my upper body swung downward and inward. I grabbed the hatch above me and pulled it inward. I knew it was going to hit either the hatch frame or my helmet. If hatch frame, fine, but if helmet, that meant I wasn't down far enough, and I would have to go back outside and try again.

Which would it be? Click! The best sound ever, as the hatch slid smoothly into place. Now all I had to do was unstow the locking handle, and crank, and crank, untilâfinallyâit was locked. Then I tried to be funny. “This place makes the snake house at the zoo look like a Sunday school picnic,” I said, referring to the fact that I couldn't see much besides a jillion loops of umbilical line. John and I took a good fifteen minutes to get that umbilical and all the rest of the space-walk equipment under control. We put it all together into one large package, which we then dropped overboard, opening the hatch for the third time in two days. This time, with no umbilical, the inside of the Gemini seemed quite spacious, and it was really easy to squeeze down far enough to get the hatch locked for the final time.

After all this, it was time for a good meal and some sleep. It was suppertime, and I had missed lunch in the rush of preparing for the space walk, and I was really hungry. I unpacked a transparent plastic tube of powdered cream of chicken soup, and filled it up with water. The water came from a gray metal water pistol with a long skinny barrel which I stuck into a small opening in one end of the bag. The water gun was the same one John and I used to drink from, being attached by a tube to a large water tank in the

back of the spacecraft. Every time you pulled the trigger, it would squirt one half ounce of water into your mouth (or wherever it was pointed). Now I mushed up the soup by squeezing the tube until all the water was dissolved, and cut off the end of the tube with a pair of scissors. I stuck the open end in my mouth and squeezed. Delicious! The best soup I had ever tasted, even if it wasn't very hot (our water was kind of cold). Also, out my window I had the most exciting view I had ever seen, so my stomach and my eyes were very happy. Having finished my cream of chicken soup, I munched on squeezed bacon cubes and watched the world go by. To save fuel, we had turned off our control system, which meant that we were slowly tumbling. Having flown fighter airplanes for years, I was accustomed to rolling and looping and even spinning, but I had never flown sideways or backward before. Now the blunt snout of our Gemini was tracing graceful arcs in the sky, sometimes in front of our direction of travel, sometimes to one side or the other, sometimes behind. It was like a beautiful roller-coaster ride in slow motion, with no noise, no banging around, no hollow feeling in the pit of the stomach. It was really fun. We were supposed to be going to sleep shortly, and I was tired, but not sleepy, and I really wanted to take the time to enjoy what I saw and felt.

back of the spacecraft. Every time you pulled the trigger, it would squirt one half ounce of water into your mouth (or wherever it was pointed). Now I mushed up the soup by squeezing the tube until all the water was dissolved, and cut off the end of the tube with a pair of scissors. I stuck the open end in my mouth and squeezed. Delicious! The best soup I had ever tasted, even if it wasn't very hot (our water was kind of cold). Also, out my window I had the most exciting view I had ever seen, so my stomach and my eyes were very happy. Having finished my cream of chicken soup, I munched on squeezed bacon cubes and watched the world go by. To save fuel, we had turned off our control system, which meant that we were slowly tumbling. Having flown fighter airplanes for years, I was accustomed to rolling and looping and even spinning, but I had never flown sideways or backward before. Now the blunt snout of our Gemini was tracing graceful arcs in the sky, sometimes in front of our direction of travel, sometimes to one side or the other, sometimes behind. It was like a beautiful roller-coaster ride in slow motion, with no noise, no banging around, no hollow feeling in the pit of the stomach. It was really fun. We were supposed to be going to sleep shortly, and I was tired, but not sleepy, and I really wanted to take the time to enjoy what I saw and felt.

We were flying at an altitude of 200 miles above a sphere whose radius is 4,000 miles. In other words, we were skimming along just above the atmosphere, which is very thin, thinner proportionally than the rind on an orange. The curvature of the earth was apparent, but it was not startling. We were moving at 18,000 miles an hour, but there was not the blur of speed that one sees from a race

car. The reason for this is that our higher speed and higher altitude combined to make things go by the window at the same rate as if we had been going lower and slower. The colors were also familiar, although the sky was absolutely black instead of blue, and one noticed the blue of oceans and the white of clouds more clearly than the green of jungles or the brown of deserts. Well, then, what

was

so different, so unusual, that I felt I could spend weeks looking out my small window?

car. The reason for this is that our higher speed and higher altitude combined to make things go by the window at the same rate as if we had been going lower and slower. The colors were also familiar, although the sky was absolutely black instead of blue, and one noticed the blue of oceans and the white of clouds more clearly than the green of jungles or the brown of deserts. Well, then, what

was

so different, so unusual, that I felt I could spend weeks looking out my small window?

It was simply that I knew how different it was, from a lifetime of crawling around the surface of this planet. It gave me a feeling of power to know I was circling the earth once each ninety minutes. Those weren't lakes going by the window, those were oceans! Look at that! We had just passed Hawaii and here came the California coast, visible from Alaska to Mexico, and my bacon cubes not yet finished. San Diego to Miami in nine minutes, and if you missed it, it didn't matter, because they would be back again in another ninety minutes. Another difference was that we were high above all weather, in pure unfiltered sunlight which cast a cheery glow on the scene below. It seemed like a better world in orbit than it did down on the surface. The Indian Ocean flashed incredible colors of emerald jade and opal in the shallow water surrounding the Maldive Islands, then on to the Burma coast and lush green jungle, followed by mountains and coastline. Then out past the island of Formosa, looking like a giant, well-fertilized gardenia leaf, and across the Pacific, over Hawaii, and now time for California once again. Incredible!

But all good things must come to an end, and now it really was time to sleep, so John and I put thin metal plates

over our windows and blocked out the spectacular view. I slept well, being by now much more accustomed to my surroundings, and, besides, I was tired and pleased from my day of space walking. After a hearty breakfast, John and I performed a couple of hours of experiments, and then it was time to come home. We did this by firing our retro-rockets, four solid-propellant rockets mounted in our tail. We were to point backward when we fired them, so that they slowed us down enough to allow gravity to bend our orbit back into the atmosphere. We were scheduled to fire our retro-rockets over the Pacific Ocean, west of Hawaii, whereupon we would begin a gradual descent and finally splash into the Atlantic Ocean east of Florida thirty minutes later.

over our windows and blocked out the spectacular view. I slept well, being by now much more accustomed to my surroundings, and, besides, I was tired and pleased from my day of space walking. After a hearty breakfast, John and I performed a couple of hours of experiments, and then it was time to come home. We did this by firing our retro-rockets, four solid-propellant rockets mounted in our tail. We were to point backward when we fired them, so that they slowed us down enough to allow gravity to bend our orbit back into the atmosphere. We were scheduled to fire our retro-rockets over the Pacific Ocean, west of Hawaii, whereupon we would begin a gradual descent and finally splash into the Atlantic Ocean east of Florida thirty minutes later.

Before we could retrofire, however, we had a long checklist to wade through. And did John and I take our sweet time! We could fire those rockets only once, and everything had better be right. If we fired them while we were pointed forward instead of backward, instead of reentering the atmosphere we would be boosted into a higher orbit, with no way to get down from it. So as we went around on our final orbit, we double-checked everything except the direction we were pointing. We checked that at least ten times. It was also traditional to use the last orbit to say goodbye to the people in the various tracking stations who had helped us. “We'll be standing by,” they told us. “Have a good trip home.” “Roger,” said John. “Thank you very much. Enjoyed talking to you. It's been a lot of fun ⦠Want to thank everybody down there for all the hard work.” John wasn't kidding. The people on the ground had really been helpful, especially in thinking up ways for us to

save fuel after we had used so much in finding our first Agena.

save fuel after we had used so much in finding our first Agena.

Other books

Surviving The Evacuation (Book 7): Home by Tayell, Frank

90 Days (Prairie Town Book 2) by Ridener, T.E.

The Cornbread Gospels by Dragonwagon, Crescent

A Voice from the Field by Neal Griffin

Katie Rose by A Case for Romance

Silence by Becca Fitzpatrick

The Tartan Touch by Isobel Chace

Last Call by Sean Costello

Mission Under Fire by Rex Byers

Cooper by Nhys Glover