Folk Legends of Japan (17 page)

Read Folk Legends of Japan Online

Authors: Richard Dorson (Editor)

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Asian, #Japanese

"I was only twenty years old at the time. Shocked by the horror of it all, I lay on the bottom of our boat and had a nightmare every night for a week. Even now, when I think of that I feel my hair stand erect with fright. I have had similar experiences several times since then."

An old fisherman told me this story.

ONE HUNDRED RECITED TALES

This story about storytelling illustrates the belief that a group of people reciting

monogatari

expect something evil to happen. Mockjoya, II, pp. 146-49, speaks of "Ghost Stories," and the custom of holding

obake

storytelling sessions on summer evenings in eerie surroundings. Mitford sets down several weird tales of "Ghostly apparitions, related one cold night in Edo by Japanese friends huddled around the brazier" (in "The Ghost of Sakura," pp. 185-87).

Text from

Chiisagata-gun Mintan Shu,

pp. 270-71.

A

YOUNG NOVICE

of a temple invited his friends over and they decided to tell one hundred tales. So they put up one hundred lighted candles in the hall of the temple. When one person finished a story in the other room, he was to come to the hall and blow out one candle. The most timid person was to begin, and the bravest one was to go last. Finally this novice and the son of the village headman remained as the last ones. Only two candles were left lighted. Then these were blown out too. Having finished the hundred stories, most of the boys went home. It was very late.

Two boys stayed in the temple with the novice. Two of the three went to sleep, but the son of the village headman stayed awake. He heard something in the room. He looked around. There appeared a ghost who picked up the novice in his quilts and carried him away. After a while the ghost came again and this time carried away the son of the sword dealer. The headman's son called out the names of the two boys, but no answer came. "They must have died. My turn will come next."

While he was thus affrighted, the first morning cock crowed. So he rose and went home. He visited the shrine to pray that such a fearful thing would never happen again.

Every time he visited the shrine he met the same girl on his way back. Gradually they became intimate, and finally they married. One evening his wife stayed in the kitchen for such a long time that the husband peeped in. The wife was blowing the fire with a hollow length of bamboo, and her face looked just like that of the ghost he had seen in the temple. Fearfully, he remembered the night just a year ago when they had recited tales. He cried out. His wife immediately ran to him and blew a breath in his face.

The husband died on the spot from that breath.

PART FOUR

TRANSFORMATIONS

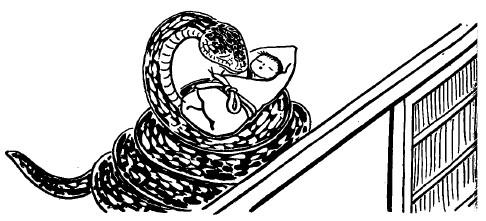

ONE COMMON THEME in Japanese legendry is the changing of shape by supernatural beings. In English folklore the witch customarily shifts her form for purposes of enchantment and bedevilment, taking a variety of animal guises. This situation is doubly reversed in Japan, where beasts, primarily serpents and foxes, take on the appearance of beautiful maidens, to seduce and even mate with mortals. Sometimes in the legends the serpent comes as a man, and sometimes a seemingly normal human being is transformed into a snake and consigned to the bottom of a pond. Serpents are usually involved in tragic romances, while foxes carry on a good deal of mischievous activity, of which seduction forms but one aspect. Badgers are also much given to illusory impersonations, although on the whole they are less feared than foxes and seem more easily apprehended. The anthropomorphic as well as the animal deities too take on human forms, appearing as beggars or forlorn women to test the piety of the folk. If aggrieved, they can permanently transform the impious mortals they meet into rocks or rats. The world revealed in these transformation legends suggests the universe of the North American Indians, whose tales describe courtships between warriors and deer-maidens and the adventures of a trickster culture-hero who assumes chameleon shapes. But the Indian legends are set in the depths of the forest, while the Japanese

densetsu

take place in towns and castles and even in the modern metropolis.

THE SERPENT SUITOR

This is one of the most popular of all Japanese tales, occurring both as fiction and as legend. Ikeda reports ninety-seven versions collected from all over Japan, besides appearances in literary classics such as the Kojiki and Shaku Nihongi, and instances from Korea, China, and Formosa (pp. 125-26). She identifies it as Type 425C ("The Girl as the Bear's Wife") calling it "Snake Husband." Thompson has the pertinent Motif T475.1, "Unknown paramour discovered by string clue," with solely Japanese references. Ikeda reports that the legendary form is attached to important local families who claim to be descendants of snakes.

Legends of a threaded needle used to detect a serpent-lover appear in W. Alexander, "Legends of Shikoku,"

New Japan,

V (1952), pp. 566, 579, "Dragon Spawn"; De Visser, "The Snake in Japanese Superstition," pp. 277-78; Murai, pp. 62-67, "Huge Serpent of Nameri Pond"; Suzuki, pp. 51-52, "The Serpent Grove." The lasciviousness of the serpent is mentioned by Anesaki, p. 332. Under "Irui Kyukontan" (Tales of Marriage between Humans and Non-human Creatures), the

Minzokugaku Jiten

classifies four forms of snake-bridegroom tales. The present story falls into the so-called spool type.

O

NCE THERE LIVED

a village headman named Shioharain Aikawa-mura, Onogun. He had a lovely daughter. Every night a nobleman visited the daughter, but she knew neither his name nor whence he came. She asked him his name, but he never told her about himself. At length the girl asked her nurse what to do. The nurse said: "When he comes next time, prick a needle with a thread through his skirt, and follow after him as the thread will lead you. Then you will find his home."

The next day the girl put a needle in the suitor's skirt. When he departed, the girl and the nurse followed him as the thread led them. They passed through steep hills and valleys and came to the foot of Mt. Uba, where there was a big rock cave. As the thread led inside, the girl timidly entered the cave. She heard a groaning voice from the interior. The nurse lighted a torch and also went into the cave. She peered within and saw a great serpent, bigger than one could possibly imagine. It was groaning and writhing in agony. She looked at the serpent carefully, and she noticed that the needle which the girl had put in her lover's skirt was thrust into the serpent's throat.

The girl was frightened and ran out of the cave, while the nurse fainted and died on the spot. The serpent also died soon. The nurse was enshrined in Uba-dake Shrine at the foot of Mt. Uba, and the cave of the serpent is also worshiped as Anamori-sama.

If a man enters this cave with something made of metal, or if many people go into the cave at the same time, the spirit of the cave becomes offended and causes a storm.

THE BLIND SERPENT-WIFE

"We have several legends told about snakes sacrificing one or both eyes for the benefit of unhappy human beings," writes Suzuki, p. 91, and gives two examples ("The Blind Serpent," pp. 91-95). The first seems based on the same outline as the text below, and this is also true for Yanagita-Mayer,

Japanese Folk Tales,

no. 62, pp. 180-82, "The Blind Water Spirit." De Visser reports a separate treatment of the theme in "The Snake in Japanese Superstition," p. 306, where an ugly younger sister drowns herself, becomes a serpent, and gives her eyeballs to a friendly maid, who must yield them to the headman; this is from Kiuchi Sekitei,

Unkonshi Zempen,

1772.

Text from

Shimabara-hanto Minwa Shu,

pp. 131-33. Told by Hiroshi Ejima in Minami Arima-mura.

A

YOUNG DOCTOR

lived at Fukae-mura with his mother. One summer day when it began showering a beautiful girl took shelter under the eaves of the village headman's house. Although she expected that the shower would soon be over, the weather did not clear up, and by and by it began raining heavily. Meanwhile the sun was going down in the west. The people of the headman's house took pity on the poor strange girl who was standing under the eaves of their house and they kindly induced her to come inside and wait till the weather cleared. Through conversations with the girl, the headman came to know something about her: that she was a maiden and came from Higo, and so forth. Since he had been asked by the doctor's mother to find a bride for her son, he thought this girl might be appropriate. So he acted as go-between, and everything went smoothly. The girl from Higo became the wife of the doctor of Fukae, and a child was born in due time.

One day when the doctor's mother opened the door into the wife's room, she was astonished to see a big serpent sleeping in the center of the room, coiled around the child and snoring. When he came home from a patient's house, the doctor saw his mother looking very pale, and he was so anxious to know the reason that his mother told him about his wife. He could not believe her story that his wife was a serpent. But the next day when he peeped into the wife's room, he saw exactly the same sight that his mother had described to him.

At last he determined to divorce his wife. She said in her grief: "I was rescued by you at the beach some years ago. In return for your kindness I came here in the form of a woman to serve you. I am a serpent in the pond on Mt. Fugen. If you cannot find a good nurse for the baby, please come to Fugen Pond." And she left him.

The doctor remembered that some years before he had rescued a white eel which the village children had been teasing. Maybe this serpent was that eel.

He searched for a nurse, but he could not find anyone. So he went to Fugen Pond with the baby, according to the wife's instructions. When he arrived at the pond, the wife appeared in the form of a woman and gouged out one of her own eyeballs. She handed it to the husband and he gave it to the child who licked it, and strange to say, milk came out of it. The doctor was pleased at this. He started back home with the baby on his back and the eyeball in his bosom. It was a dark night. The doctor met a few patrolling samurai on his way through the mountain. They became suspicious on seeing the doctor's bosom swelled up with the eyeball, so they examined him and found a fine jewel ball. The doctor was robbed of the precious eyeball by those men.