Folklore of Yorkshire (11 page)

Read Folklore of Yorkshire Online

Authors: Kai Roberts

Unsurprisingly, the boy resented his confinement and one day asked permission to visit the celebrated Topcliffe Fair. When the giant refused, the boy decided that he would take his leave anyway. He waited until the giant had gorged himself and fallen into a slumber, took the knife it had used to cut bread and like Sir Guy D’Aunay stabbed directly into the monster’s eye. Unfortunately, this did not kill the giant straight away and the brute rose up, blocking the only door. But the boy still had a trick up his sleeve and as the giant raged, he killed and then skinned his master’s dog. Draping the pelt over his shoulders, the boy dropped down onto all fours and began to bark. Unable to tell the difference, the half-blind giant let the boy crawl through his legs to the door and safety.

The giant must have succumbed to his wound eventually, as a tumulus known as Giant’s Grave once stood beside the mill at Dalton – although it had long since been destroyed by the time the legend was recorded in the late nineteenth century. Whilst this has something in common with the tradition of landscape-shaping giants, the Dalton example is in all other respects a typical ogre, much like the giants of Wighill and Sessay. It is possible that these three represent a corrupted memory of some brutal outlaw leader, but they are all conceived as a classic bogeyman figure and by the time these legends were recorded, they were probably told only as bedtime stories to children or to tease gullible visitors.

This certainly seems to be the case with the giant that occupied Yordas Cave in Kingsdale. Although this cavern is now accessible to anyone with a sturdy pair of boots and the spirit of adventure, during the nineteenth century it was a show-cave, with a fee charged for guided tours. One sightseer records being shown, ‘the great hall of Yordas – the fabulous giant from Norway – and there we see his throne, his bed-chamber, his fitch of bacon, his mill and his oven, wherein he ground and baked the big white stones or the bones of naughty boys and girls into bread.’ However, it is unclear if this is anything more than an invention of the tour-guide. There is no Nordic giant named Yordas and the name more likely derives from the Old Norse phrase

jord ass

meaning ‘earth stream’ – doubtless a reference to the subterranean waterfall which dominates the main chamber.

Nonetheless, this evolution (or devolution?) is a familiar folkloric process and the transition of narratives from sincere belief, to fireside yarn, to children’s story is widely recognised. Whilst it now seems excessive to claim that legends encode the beliefs of pre-Christian cultures – as many early folklorists did – a kernel of historic conviction may still be found in many of these narratives. Whether that is the animistic personification of prominent landscape features, an incredulity at the size of prehistoric megaliths or the memory of some feared local tyrant, the stories provide a valuable glimpse into the concerns and cosmologies of the people who first told them and the generations that preserved them.

F

AIRY

L

ORE

![]()

I

n the summer of 1917, ten-year-old Frances Griffiths and her sixteen-year-old cousin Elsie Wright claimed to have captured two photographs of fairies playing around Cottingley Beck, near Bradford. By 1920, news of these remarkable images had reached the creator of Sherlock Holmes and prominent Spiritualist, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who was working on an article about fairies for the Christmas edition of

The Strand Magazine

. At their request, the two girls produced another three photographs and all five pictures were unleashed upon the general public over the following year to a considerable storm of publicity. Although very few commentators were as credulous as Doyle, the story nonetheless provided a popular talking point and gripped the British imagination for many decades thereafter.

In 1983, improved photographic analysis techniques finally pushed the cousins into admitting that they had faked the photographs, using cardboard figures copied from a popular children’s book of the era. Whilst a study of folklore is not the place to examine the historical and philosophical dynamics that led to the hoax being so readily accepted by Doyle and his ilk, or the public sensation that followed, the episode can nonetheless be seen as a manifestation of a centuries-old fairy tradition in Yorkshire, a tradition in which Frances Griffiths and Elsie Wright had once been thoroughly initiated. For although Elsie disavowed all the photographs, Frances continued to maintain that the fifth and final image was genuine, and both women insisted until their dying day that they really had seen fairies around Cottingley Beck.

In the previous century, a number of striking accounts of fairy sightings were recorded in the region, often purporting to be the personal experiences of respectable, upstanding citizens whose word could not be questioned. In the mid-1800s, for instance, a labourer named Henry Roundell was known to have encountered fairies early one morning somewhere in Washburndale, possibly in the vicinity of Fewston. When the report was published in 1870, the journalist’s correspondent saw fit to note, ‘A shrewd fellow he was, who knew quite well the difference between a pound and a shilling: and a steady church-goer … If he had not been such an exceedingly respectable man, all would have been set down at once to a mere drunkard’s fancy.’

Roundell claimed that after rising unusually early one morning, he had set off to hoe a field of turnips and upon arriving at his destination a little before sunrise, noticed that the leaves seemed to be:

… stirring strangely. When he looked again he saw that what was moving about were not turnip-leaves at all. Between every row of them was a row of little men, all dressed in green, and all with tiny hoes in their hands. They were hoeing away with might and main; and chattering and singing to themselves meanwhile, but in an odd, shrill, cracked voice, like a lot of field-crickets. They had hats on their heads, something in the shape of foxglove bells, Roundell thought, but he was not near enough to distinguish them plainly, only he was quite certain they were all dressed in green, the same colour as the turnip leaves.

Up until this point, the story is in many ways atypical. It is quite unusual to find fairies engaged in any form of labour; often they are portrayed as decadent, hedonistic beings forever revelling in the moonlight and dependent on pilfering the fruits of human endeavour for the necessities of life. However, it concludes as so many fairy narratives do. Roundell proceeded to stumble over the gate to the field and alert the field’s occupants to his presence, whereupon they all immediately fled: ‘Whirr! Whirr! off went the little men like innumerable coveys of partridge.’ If there is any recurrent theme to narratives concerning the fairies, it is that they are shy creatures who resent humans spying or interfering in their affairs.

Yorkshire is the scene of one of the earliest recorded fairy narratives in England and even several hundred years prior to Roundell’s experience, these creatures were portrayed as profoundly hostile to uninvited human intrusion. The legend was documented around 1198 by the monk, William of Newburgh, who wrote that he had known it since his childhood, suggesting an even older provenance. Indeed, it is one of the most common migratory legends in English fairy lore and a version was recorded in Gloucestershire only thirty years later. Although William does not explicitly identify the location of this fairy encounter, it is clearly supposed to be Willy Howe, a Bronze Age burial mound on the Yorkshire Wolds, close by that mysterious stream, the Gypsey Race. The theme of hollow hills and prehistoric burial sites is a common one in fairy lore.

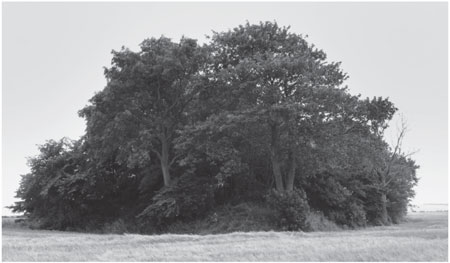

Willy Howe, a Bronze Age tumulus on the Yorkshire Wolds haunted by fairies. (Kai Roberts)

In William’s account, a peasant returning home late at night was disturbed by the sound of singing and feasting emerging from Willy Howe as he rode past. Deciding to investigate further, he discovered a door into the barrow and beyond this portal, ‘a large and luminous house, full of people, who were reclining as at a solemn banquet’. As the peasant entered, an attendant offered him a cup, but rather than drink from it, he poured out the contents and tried to pocket the vessel. Unfortunately, the fairies noticed his actions and ‘great tumult arose at the banquet’. The assembled host then pursued him as he fled from the barrow and he was only able to escape thanks to the swiftness of his horse. However, the adventure had been worth it. The purloined cup proved to be fashioned from an unknown material and of such rare quality that he later presented it to King Henry I.

Perhaps it is unwise to assume that the fairies seen by Henry Roundell and William of Newburgh’s rustic were the same category of being. Folklorist Jeremy Harte has observed that during the medieval period, they were typically referred to as elves and the idea of a universal class of ‘fairies’ did not emerge in popular tradition until much later. The term ‘fairy’ has an Old French root and whilst it was a popular term in late medieval romances, primarily consumed by a courtly audience, the word does not seem to have appeared in vernacular English until the eighteenth century. It was only following this that fairies in native folklore began to assume the characteristics which we typically ascribe to them today. For instance, diminutive size was not a characteristic of any fairy-type entity until the Victorian period; it is instructive that whilst Roundell describes the fairies he saw as ‘tiny’, William of Newburgh makes no such reference.

It may be, therefore, that during the nineteenth century a number of diverse entities were subsumed under the catch-all term ‘fairy’, distorting their original significance. Given the passion of Victorian collectors for taxonomising, this would hardly be surprising. One feature common to fairy lore of all ages, however, seems to be the idea of a parallel society to our own, but one that is largely invisible to us and sometimes antagonistic. Indeed, the seventeenth-century Scottish minister, Reverend Robert Kirk, dubbed it ‘The Secret Commonwealth’. This society also seems to have been more intimately connected to the natural world than our own and it is significant that whilst ideas about fairy physiognomy and behaviour changed over the centuries, the places they were supposed to inhabit remained more constant – in the northern counties at least.

Thus, when Thomas Wright visited Willy Howe around 1861, he discovered that the twelfth-century legend was still well known in the locality. Assuming that Victorian farmers on the Wolds were not familiar with the work of medieval chroniclers, the narrative had survived almost 700 years through oral transmission alone – although the tale told to Wright had a slightly different twist to the conclusion. In that version, when the vessel was offered to the peasant at the banquet, it appeared to be made from pure silver; yet when he got it home, he discovered that it was nothing more than base metal and mostly worthless. Wright also notes that few locals would pass Willy Howe after dark and were greatly concerned when some antiquarians had previously attempted to excavate the barrow, fearing the supernatural retribution that might follow.

Another story about Willy Howe was recorded by William Hone in his

Table Book

of 1827. In this story, a fairy maiden was uncharacteristically smitten with a local man and she told him that if he visited the top of the barrow every morning, he would find a guinea coin awaiting him. She only warned him not to inform anybody else. At first, the man heeded the injunction and he always attended the spot alone, each time finding his guinea reward as promised. But clearly this secret knowledge was too great for him to bear alone and eventually he invited a friend to accompany him to the top of the Howe. Following this, not only did the gift of guineas cease, but ‘he met with a severe punishment from the fairies for his presumption’. Sadly, Hone does not record the exact nature of the retribution meted out.