Food Over Medicine (4 page)

Read Food Over Medicine Online

Authors: Pamela A. Popper,Glen Merzer

I’d say that not understanding the importance of dietary pattern is the overarching issue. People think that they’re going to improve their diets by eating soy twice a week. Or they read an article saying blueberries can reduce the risk of cancer, so they eat blueberries every day for six months. They end up gaining four pounds, and their health deteriorates because it turns out that neither blueberries nor any other single food can fix what’s wrong with them. It’s only by changing the fundamental dietary pattern that they can fix what’s wrong. Those are some of the ways in which Americans have gone astray, why they’re so confused and frustrated.

GM:

Do you see supplements as an attempt to get by with minimal changes?

PP:

Yes. It goes along with Americans’ unending quest to eat a healthier version of their bad diets. “I’m eating chicken and fish instead of beef. I’m drinking skim milk instead of whole milk. I use only organic, cold-pressed olive oil.” Well, it doesn’t matter what kind of oil. Again, you need to understand the dietary pattern that promotes health. It’s the entire diet that the average person eats, including many of my very well-educated friends who believe they’re eating healthfully. It’s their entire diet that’s appalling from the standpoint of both macronutrients (protein, carbohydrate, and fat) and micronutrients (vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals).

GM:

I read about a study showing that 90 percent of Americans believe they eat a healthy diet.

PP:

Yeah. Isn’t that amazing? Then it must be just the other 10 percent responsible for the 40 percent obesity rate.

GM:

Don’t you hate it when a small minority ruins it for everyone else?

PP:

People have the idea that they can eat whatever they want because it tastes good; they have no concept of the relationship between diet and human health. You see this in young people, too. Young people especially assume that they’re invincible.

They think they can eat, drink, and be merry, with no price to pay. And then one day, there is. They go to the doctor and realize they’ve gained twenty or thirty or fifty pounds, and their cholesterol is out of control. There’s a complete disregard, even in the medical community, for the idea that what goes into your mouth influences your health. That’s the root of the problem.

GM:

I’ve got a candidate for the worst food out there. I saw this on a Sunday morning news show. At the Iowa State Fair, the big hit this year was deep-fried butter.

PP:

Deep-fried butter?

GM:

On a stick. Four ounces of butter deep-fried, dipped in honey, and topped with a sugary glaze.

PP:

Does it come with an angioplasty?

GM:

The reporter, Jake Tapper, who’s an intelligent guy, took a bite out of it on television, as if he thought it was amusing. He was showing us he was a good sport, a man of the people. I’ll bet he has a great life as a major media figure in Washington, and I’m sure he’d like to attend his children’s weddings one day, but there he was, eating deep-fried, sugar-glazed butter. Now, if he was doing a story on crystal meth being all the rage in Iowa, I don’t think he’d sample it.

PP:

That’s what I’m saying. It’s this eat, drink, and be merry approach to foods that are poisons that is truly deadly.

GM:

I’m curious what first step you ask people to take to begin their dietary transformations. When people join The Wellness Forum and they are obese and on cholesterol medication, having a kitchen loaded with meat, cheese, soda pop, cookies, and chips, do you tell them to just go home and throw everything out?

PP:

I tell them to take it to a church or food bank. There are people who are hungry and are worried not about cardiovascular disease and diabetes but about feeding their kids. So the best gift you can make is to take that food that doesn’t serve you anymore and give it to people who desperately need food tonight. Then go buy the right stuff. We have to get over some of the mental images associated with this: I spent all this money on food and don’t want to throw it out or give it away! Well, if you end up having a heart attack tomorrow, are you going to say, “Hey, I’m so glad I ate that bacon and got my money’s worth. Sure, I had a heart attack, but I didn’t waste a nickel!” Nobody ever sits in my office as a result of making bad choices and ending up in a bad health situation and says, “Yeah, I know I’ve got this breast cancer, lupus, or diabetes now, but it was so worth it because all that animal food and processed food was delicious.” Get the stuff out of your house. Leave it behind. Leave your old life behind and join me. Let me take your hand and take a giant leap over to where the healthy people live.

If I could find a way to make people understand this quickly and easily, I know I’d be a billionaire. If I could develop a pill where people could live inside my body for just twenty-four hours and then go back to their own, we’d have no trouble convincing people to eat like this because they would feel how great it is to feel alive and energetic and to be able to run around eighteen hours a day. I want them to experience that. That’s the only way we’re going to get compliance. That’s the only way people are going to get with the program.

THE PROGRAM

....................................

GM:

Let’s talk about the optimal diet. There’s a theory out there that we’re all different and we should choose our diet according to our blood type or our genetic makeup or our personality type or our astrological sign, and that the optimal diet is one thing for one person and a vastly different thing for another person. Is there any truth to the idea that different people need wildly different diets, or are we mostly alike in what we ought to be eating?

PP:

We’re shockingly alike. The only thing that differentiates us significantly is food allergies. My attorney, who died a couple years ago at sixty-one, was in his fifties when I met him. He had been allergic to cherries, peaches, and apricots since he was five. Well, he could eat a plant-based diet, but since cherries, peaches, and apricots sent him into anaphylactic shock, we kept him away from those foods. That would be an example of a genetic situation; stay away from three specific foods.

GM:

Wait a minute. He ate a plant-based diet, but died at sixty-one?

PP:

Well, he cheated a lot. He died of noncompliance. He would say he was on a plant-based diet, but he never gave up cheeses and salmon, and he ate olive oil and sweets. One day it caught up with him and he had a massive heart attack. He was a successful man and he liked to live large; as a consequence, he died in an instant. It was a tragic example of how you have to get the whole diet right, not just get half of the equation right.

But with reference to this idea that people are different and therefore some people should eat different types of diets because of their ethnicity or their blood type, there’s no solid evidence. I come to all my conclusions based on medical evidence. If you wonder whether there’s anything to the blood-type diet, do PubMed searches. Anybody can do it. You’ll find absolutely no published evidence indicating that blood type makes a difference in long-term health outcomes. I get very frustrated because the promoters of these blood type diets and metabolic diets and caveman diets have made millions and millions of dollars promoting these programs to patients and the general public. And they spend none of that money on proving their hypotheses. I love the way Dr. T. Colin Campbell, the author of

The China Study

, put it when he was going head-to-head on the Internet with someone who was criticizing him: “Put your theory to the test because what you’re essentially saying by refusing to do so is that research is a luxury to be enjoyed by some but not required by all.” And that’s a rather insulting attitude to those of us who are serious because I, for one, rigorously adhere to what the science says about all aspects of nutrition. There simply isn’t a shred of evidence that the caveman diet or these other fad diets help achieve or maintain optimal health in populations today. These people are writing storybooks. They may be very interesting, but they’re not to be confused with science. They cite a lot of studies, but a close look shows that they misinterpret them to promote their diet, and they never conduct a single study of their own to prove their case.

Let me give you an example of how storytelling can confuse the issue. When I conduct lectures, invariably I’ll have somebody raise his hand and say, “My uncle ate bacon, eggs, and cheese three times a day and he lived to be ninety-four and died in his sleep. How do you explain that?” And I will say, “I believe you. I believe that happened. But if you delve into the published scientific information that we have, it clearly shows that is not the likely outcome for other people who engage in that behavior.” So that’s a story. It’s probably a true story. It has nothing to do with the advice that we should give to the general population.

GM:

You’ve got to love the premise of the caveman diet books, that we should, for some reason, eat the diet of our primitive ancestors. Maybe to prove that civilization has not come that far. I actually have a theory that the first vegan was a caveman who discovered that it’s easier to sneak up on a plant.

Anyway, since we’re shockingly alike as humans, what should our diet be? Let’s begin with fat. What percentage of calories from fat should we have in our diet? There are those who recommend a plant-based diet and emphasize that it should be low-fat, roughly 10 percent of calories as fat. And there are others, even some who recommend the vegan diet, who say no, we need a healthy amount of nuts and seeds and avocados, a higher percentage of fat. And then, of course, there are the diet book hucksters, like Dr. Barry Sears and the late Dr. Robert Atkins, who promote a diet that’s 30 percent fat or more.

PP:

Let’s disregard the hucksters because they’re not worth our time. But between the serious scientists advocating a low-fat, plant-based diet and the serious scientists advocating a plant-based diet that’s somewhat higher in fat, I think the answer is in the middle. I don’t like to restrict people more than is necessary; my general recommendation to people is an upper limit of 15 percent, which is still pretty low. It’s very achievable if we get oils out of the diet and use nuts and seeds and olives and avocados as parts of dishes that we eat, but don’t go out of our way to eat a bunch of fatty plant foods all the time. Now, for somebody who has coronary artery disease, or who needs to lose a hundred pounds, we want to get him down to the 9 to 11 percent range in terms of fat, which means he’s not going to be consuming avocados and nuts and olives. I recommend an upper limit of 15 percent and a lower limit of 9 to 11 percent for people who have certain kinds of diseases.

GM:

Allow me to cite a mainstream nutritionist: Walter Willett of the Harvard School of Public Health. He argues that low-fat diets show no improvement in health outcomes compared with higher-fat diets; the important thing is to have good fats—polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fat. He cites a

Journal of the American Medical Association

study published in 2006,

1

an eight-year study of more than 49,000 women that he says demonstrated no improvement in outcomes from a low-fat diet.

PP:

Willett is not the only person who finds that a low-fat diet does not provide benefit. The problem is his definition of a low-fat diet, and definitions are something that plague nutritional research. In Willett’s Nurse’s Study, for example (I think the government has invested roughly a hundred million dollars in this whole project), the lowest amount of fat these women ever consumed was in the vicinity of 29 or 30 percent! I don’t think any of us who advocate a plant-based diet has ever told anybody that a diet that contains 30 percent of calories as fat is protective against anything. The other thing I’ll point out about Willett’s research and the Nurse’s Study is that one of the ways in which people accomplish a “low-fat” diet is often to eat fat-free dairy products. The detrimental effect of the concentrated protein in those dairy products often overcomes the benefit of any fat reduction, even if it were to reach the target level.

GM:

Okay, so let’s say I’m convinced that I should aim for roughly 10 to 15 percent of my calories as fat. How do I execute that? I couldn’t tell you with any accuracy the percentage of calories I ingest is fat. Are you recommending that people somehow count their calories and calculate the percentage derived from fat?

PP:

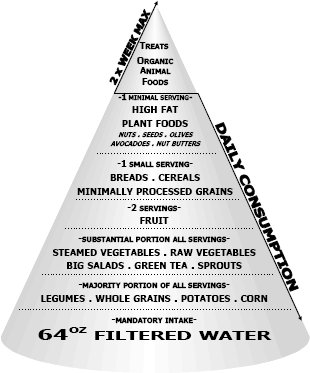

I tell people, if you’re eating according to our pyramid, you’ll be just fine. I can’t teach people to be either calorie counters or nutrient counters because it can’t be done. And I use myself as an example. Today for lunch I had a salad with one of Wellness Forum Chef Del Sroufe’s fat-free dressings and a rice and vegetable casserole. So I had a nice big portion of this casserole and a big plate of salad with dressing. In order for me to tell you how many calories I ate, I’d have to come back here to my office with a database and feed in fairly accurate information about how many pieces of broccoli I ate, how much rice was on the plate, and how much dressing I put on the salad. Of course I would have no clue. So if somebody like me, with my background in nutrition and my resources, can’t figure out what I had for lunch from a calorie and nutrient standpoint, how do we take a busy CPA who’s preparing somebody’s tax return and teach her to do it on a lunch break? It’s obviously not doable.

What you have to do is teach the right dietary pattern. Just stay attuned to the principles of the diet. The only way you’re going to mess it up is if you start treating yourself all the time, or the oils start creeping into the diet and you start eating those items at the top of the pyramid with a great deal of liberalism. But if you stick with the basic food groups that we’re talking about, you’ll get full, you won’t develop a weight problem, and you’ll lose weight if you need to. You just can’t overeat. I couldn’t have possibly eaten another plate of food today; it would have been too much bulk.

THE WELLNESS FORUM’S

Eating Plan

GM:

We’ve discussed fat. How about protein? I find that when people talk about nutrition, their concerns tend to be their weight and their protein intake. Do you find that’s what people are most concerned about?

PP:

Those are two major anxieties, but people have lots of misdirected concerns. I have people coming into my office with serious health and weight problems, and they’re worried about the plastic in water bottles and about all kinds of things that may be concerning but they’re hardly the main issue. Americans are very distracted by information that isn’t pertinent at the expense of getting to the information that is pertinent.

People are concerned about their weight, but not enough of them, in my opinion. There’s an interesting phenomenon going on in our country and it’s the way that we’ve simply accepted our increasing weight. When I was in high school, there were more than seven hundred kids in our graduating class and only a handful of them were overweight. Now most of the students in graduating classes are overweight. People who are overweight look around and everyone looks like them; they don’t feel particularly bad about it or feel compelled to do something about it right away. And that’s an insidious trend because being overweight puts you at additional risk for every disease you don’t want to get and for dying from those diseases.

Regarding protein: it’s all but impossible to design a diet that has enough calories every day that doesn’t contain enough protein because protein needs are so low. Excretion studies have shown that protein needs for normal adults may be as low as 2.5 percent of calories.

2

Human breast milk, which fuels most rapid growth of humans during our entire time on the planet, contains only 6 percent protein.

3

So there’s not much chance of protein deficiency in any diet of caloric sufficiency. I’ve told people, just go to the USDA food database and start entering any combination of foods that add up to 1,500 or 2,000 calories a day; you’re going to see that it’s impossible to become protein deficient eating any combination of food. Our problem, by contrast, is that we eat way too much protein.

GM:

What’s the risk there?

PP:

We now know that animal protein consumed in excess of what humans need becomes a powerful cancer promoter, based on Dr. Campbell’s studies as reported in

The China Study

.

4

Even if you consumed a really high-protein, plant-based diet, the fact remains that the body’s need for protein is actually very low. So if you consume too much protein, even plant protein, you simply have to get rid of the excess; we can’t store much protein. What the body will do is convert some of the surplus protein to carbohydrate because that’s readily usable for energy. In the process of doing this, the body has to get rid of nitrogen from the amino acid chains, as carbohydrate does not include nitrogen.

5

As the body releases nitrogen from the amino acid chains, the nitrogen throws off a lot of toxic by-products like urea and ammonia, which are detoxified by the kidneys and liver, causing a lot of stress on those organs.

GM:

So we basically have this word—protein—that enjoys a great reputation. We have whole industries that are set up to provide us with an abundance of protein, whether it’s in the form of a snack bar or a highly concentrated protein supplement. And you’re saying that it’s really just a myth that all this protein is good for you? That if protein had the lousy public relations guy that starch has, we might not have all these protein bars in health food stores?

PP:

Yes, and we would be healthier. The myth goes back, as I learned from Dr. Campbell, to protein’s origin as one of the first nutrients discovered. A lot of benefit was attributed to it because if you withheld protein from lab animals, they died. It was around 1839 when protein was discovered, and researchers at the time attributed all this magical quality to it.

My gosh, without it people will die!

And that’s true—it’s a necessary nutrient—but they exaggerated the benefit, especially by assuming that since a little is indispensable, a lot must be salutary. The belief never got corrected, even when evidence began to show that their inferences were wrong. Russell Chittenden did some experiments back in the early 1900s on students eating a low-protein diet and found that they thrived; even the athletes performed better on it.

6

But once an idea takes hold and becomes part of the conventional wisdom in the health field, it is very hard to undo. It’s very frustrating. People in the health field are not easily persuaded by facts.