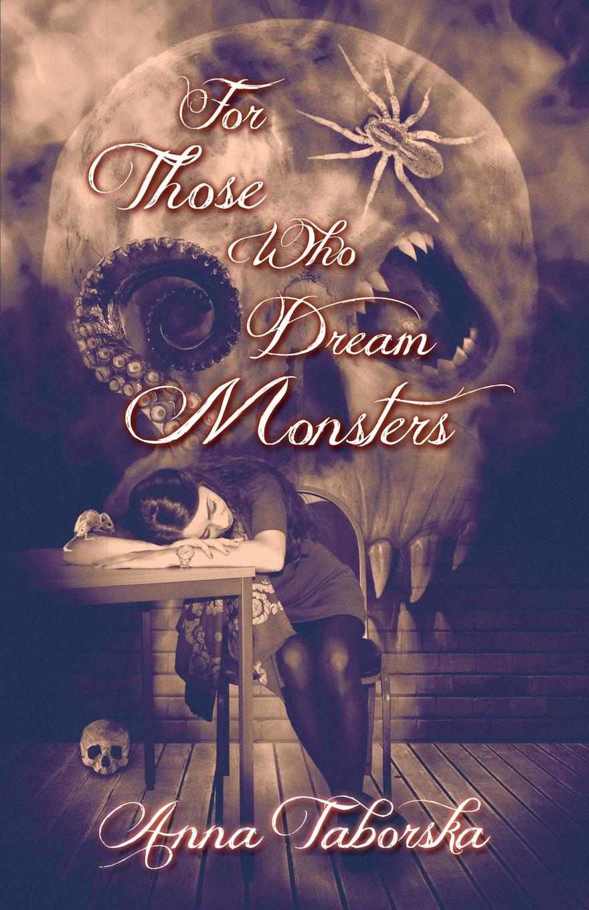

For Those Who Dream Monsters

Read For Those Who Dream Monsters Online

Authors: Anna Taborska

What are you afraid of? What are you haunted by?

What waits for you in the dark?

Face your fears and embark on a journey to the dark side of the human

condition. Defy the demons that prey on you and the cruel twists of fate that

destroy what you hold most dear.

A sa

distic baker, a psychopathic physics

professor, wolves, werewolves, cannibals, Nazis, devils, serial killers, ghosts

and other monsters will haunt you long after you finish reading

FOR THOSE WHO DREAM MONSTERS

by

Anna Taborska

18 tales from the abyss.

With chilling illustrations by Reggie Oliver.

“…

Anna is nothing if not a cruel blade when it comes to scary and horrible

fiction.”

Paul Finch, author of

Stalkers

and

Sacrifice

“Anna Taborska's fiction combines an unflinching eye for human cruelty and evil

with a deep compassion for those who suffer from it. Stark imagery and

psychological truth are the hallmarks of her work; she's a powerful writer

we'll be hearing a lot more from in years to come.”

Simon Bestwick, author of

Tide of Souls

and

The Faceless

“

…

surely among the grimmest contemporary horror authors

(I mean that as a compliment)

…

”

Demonik, Vault of Evil

“Anna Taborska’s fantastic,

surreal, dark fantasy

…

is still seared in my memory.”

Colin Leslie, The Heart of Horror

“

…

nothing short of

chilling.”

Tom Johnstone, The Zone

Published by Mortbury Press

First Edition

Paperback published 2013

E-version 2015

All stories in this collection copyright © Anna Taborska

Illustrations and introduction copyright © Reggie

Oliver

Cover art copyright © Steve Upham

ISBN 978-1-910030-01-1

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organisations,

places and events are either the product of the author’s imagination or are

used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or

locales is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by

any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise)

without the prior permission of the author and publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade

or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the

publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in

which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being

imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Mortbury Press

Shiloh

Nant-Glas

Llandrindod Wells

Powys

LD1 6PD

For those who dream monsters.

It is not supposed to be a good thing to be in someone’s black books. An

exception may be made in the case of Charles Black’s ground-breaking Black

Books of Horror. I have read many excellent stories in his anthologies and have

met their authors and found them to be, without exception, very delightful

people. Since joining Charles’s ‘stable’ I can proudly number among my friends

not only Charles himself but many of his writers, including John Llewellyn

Probert, Thana Niveau, Kate Farrell, Mark Samuels, Simon K. Unsworth, and Anna

Taborska.

I first encountered Anna Taborska’s work in the sixth

of Charles’s Black Books. The story was called ‘Bagpuss’ – it is included in

this volume – and I was immediately struck by its originality and the

excellence of its writing. Here is an authentic and exciting new voice in

horror writing, I thought. I immediately got hold of and read whatever stories

by her that I could, and my subsequent readings more than confirmed the first

impression.

The truth is that in all genres, and perhaps that of

‘horror’ in particular, writers tend to fall into certain easily recognisable

styles and themes. They move along predetermined grooves, and they may do so

well or badly, but in so doing they produce work which is not distinguishable

from the general run, and therefore, in the end, not very distinguished. Anna’s

work has an individual feel about it, a personality. She has a very acute sense

of personal suffering which is conveyed in poignant but never excessive detail.

She does not commit the fault to which most minor writers of horror are prone,

that of making her ‘victims’ mere cyphers, puppets into whom the storyteller

can stick pins at will and without conscience. There is real pain in these

stories and the horror is conveyed on a deep psychological level.

Nor is she one of those writers who, in their

individuality, pursue one particular theme or atmosphere to destruction. “Damn

him, he is so various!” said Gainsborough in exasperation at his contemporary

and rival Sir Joshua Reynolds, and the same could be said of Anna Taborska.

Here in one generous volume are eighteen stories in a variety of settings: the

United Kingdom, the United States, Africa, Eastern Europe, the present, the

past. She deals movingly with the matter of the Nazi Occupation of Poland and

the Holocaust (‘Arthur’s Cellar’, ‘The Girl in the Blue Coat’) but from a very

personal and individual angle. ‘Dirty Dybbuk’ is a story based on Jewish folk

myth; others such as ‘Rusalka’ and ‘First Night’ take their inspiration from

Europe’s rich tradition of fairy tale and legend. We enter the film world for

‘Cut!’ and that of non-governmental organisations for ‘Buy a Goat for

Christmas’. There is mordant satire in ‘Tea with the Devil’ and an exploration

of our deepest and darkest fears in ‘Underbelly’. There are wolves in ‘Little

Pig’; there is witchery – or imagined witchery – in ‘The Creaking’. I could go

on, but I would become exhausted: readers should have the pleasure of

discovering for themselves how constantly Anna Taborska breaks new ground.

“Damn her, she is so various!”

And yet, and yet… Through all this wonderful

diversity runs the thread of a particular sensibility: a very deep compassion

for the sufferings of humanity, and a poetic quality in the writing that

suddenly lifts horror into a world of strange and terrible beauty. Anna is the

daughter of a great Polish poet, and a poet herself: it shows.

It is for these reasons that I asked Anna if I might do some illustrations for

her first volume of stories. I have hitherto only illustrated my own work and

have no plans to do so for anyone else, but Anna Taborska’s work has a special

quality which evokes powerful and seductive visual imagery. This is hardly

surprising since Anna is an award winning film maker, a mistress of the moving

image. It is something we have in common: we both have a background in the

performing arts, albeit slightly different branches. I began my career as an

actor and playwright, and I tend to write my stories in ‘scenes’ as a result;

Anna, from her more film-orientated perspective, does the same, and this is

what gives her work its dynamic quality as well as its strong visual stimulus.

I immensely enjoyed entering the strange and terrible

world of Taborska. Many of the stories prompted not one but several vivid

images, but I decided that one per story was quite enough: any more might prove

too tiring both for me and the reader. I can truthfully say that any merit

these illustrations have can be directly attributable to Anna’s pen rather than

mine.

Of one other thing I can assure the reader: there is

more to come from that pen of Anna’s and it will be of the same devastatingly

high quality.

Reggie Oliver

Suffolk, August 2013

HUMAN

The cat had the uncanny ability of

seeming to be in two places at once, and it appeared logical to the man that he

should name it Schrödinger. The cat evidently approved of the name, purring as

the man tried it out.

“Well,

Schrödinger, I expect you

must

want some dinner

today

?” the man

asked, backing away from the plate of cat food to allow the animal a chance to

feed. But the cat stayed where it was, high up on the kitchen cupboard, and

refused to give the cat food the time of day, just as it had refused milk and

water, and even ham.

The man had first come across the cat on his return from work the previous day.

It was thin and dirty, a mud-smeared black, with cold green eyes and a tattered

left ear. The pitiful-looking thing was stretched out on his doorstep and

refused to budge, even as the man approached. Instead, it fixed him with an

expectant stare and weaved its tail from side to side. The man studied the cat,

and a long-forgotten joy stirred within him.

Ever since he was a child, the man had enjoyed torturing animals. His

grandfather had bought him a butterfly net, and the boy quickly worked out that

if you rubbed too much of the colourful dust off a butterfly’s wings, it had

trouble flying. And things got even more interesting if you pulled off its

wings altogether and put it on an anthill. You could watch the black specks of

the ants swarm all over the wounded intruder; watch the butterfly that was no

longer a butterfly, but a fascinating broken thing, try to lift itself out of

the writhing mass of small stinging creatures, helplessly flailing its long

thin legs, its proboscis furling and unfurling in some strange insect rhythm of

pain.

Butterflies

continued to fascinate for a long time, but eventually the allure of real

animals – one which screamed and bled – took over from those that merely

twitched pathetically. After much begging and family debate, he was finally

given an air rifle for his birthday, but sadly this was confiscated when he

moved up from shooting crows and squirrels to shooting the neighbours’ pets.

If

necessity is the mother of invention, then a twisted imagination is its father,

aunt and uncle. The boy came to understand that the air rifle, which he had so

mourned, wasn’t even a drop in the endless ocean of possibilities when it came

to inflicting suffering on anything small and fluffy that had a heartbeat. And

the smaller and fluffier it was, the easier it could be lured with a warm tone

of voice, a friendly smile, a tickle behind the ear and, if all else failed, a

piece of ham.

The

boy tried a variety of techniques on his victims: dismemberment,

disembowelment, decapitation, throwing off the roof or out of a window, the

breaking of individual bones with a blunt instrument, bloodletting,

crucifixion, and even electrocution – he was particularly good at this, as he

had an excellent science teacher at school and displayed a definite propensity

for the subject. But his favourite was luring a cat with the promise of food or

affection, locking it in a cage and carrying it to his parents’ roof, where he

would douse its tail with petrol and set it alight before pushing it headfirst

down the drainpipe. The trapped animal, its tail ablaze, would scream all the

way down the drainpipe until it got stuck in a bend, where it would burn to

charred bones and then fall out the bottom. This method only worked on small

cats and kittens, but could also be extended to some breeds of puppy. The boy’s

attempts to involve the little girl next door in his pastime resulted in his

being sent to a boarding school run by monks, where his sadistic horizons

expanded to the use of canes, whips and rulers.

The

boy left school with top results in science and went on to university, where

his interest in animals waned somewhat, as his physics studies and

unreciprocated fascination with girls led him to attain a First Class degree,

despite almost being sent down for peeping through a female student’s bedroom

window. He stayed on in academia, eventually becoming a lecturer at a reputable

university, where he could continue to indulge in physics and his

unreciprocated fascination with girls.

And now here he was, trying to get home after a tiring day of lectures, and

this scruffy, ugly cat was lying on his doorstep, as if daring him to gouge out

its eyes and cut off its paws. Old passions awoke within the man, but he was

too tired to act on them. He picked up a piece of brick that was lying in the

roadside and aimed it between the cat’s eyes. Just then a piercing pain shot

through the man’s temple. He dropped the brick and put his hands up to his

head. As quickly as it had come, the pain was gone, but the man was left

feeling bewildered and a little dizzy. As he rubbed his eyes to clear his head,

he heard a voice close by his ear.

“Let

me in,” it said.

The

man spun round, but there was nobody nearby – only the cat sprawled on his

doorstep, eyeing him like a scientist eyes a mildly interesting specimen before

dissection.

“Let

me in,” the voice continued, “and I’ll show you things you’ve never seen … I’ll

take you to places you can’t begin to imagine.”

The

man closed his eyes for a moment. When he opened them, the voice was gone and

he felt his normal self again. He looked at his front door; the cat was no

longer reclining, but sat alertly a couple of feet away from the door, as if

waiting for the man to open it.

What

the hell?

thought the man. If the cat

wanted to come in, then let it. He was tired now, but he would amuse himself

with the animal later. He opened the door and stood back to let the cat in. It

eyed him suspiciously for a moment, then darted past, leaping over the

threshold and heading straight for the kitchen.

The

man followed it, locking the door behind him. He put his briefcase down in the

hallway and went to see what the cat was doing. The kitchen was bathed in

darkness and before the man switched on the light, he caught sight of the cat’s

eyes glowing in the shadows by the sink. But as the light from the overhead

lamp illuminated the room, the man saw that the cat was not by the sink.

Surprised, he looked around and spotted the creature sitting high on a kitchen

cupboard, peering down at him with some curiosity and possibly a hint of

malevolence.

“Well

I’ll be damned,” he told the cat. “The rough and tumble world of quantum

physics would have a field day with you.” The man laughed at his own wit and

went to the fridge to get some milk. If he was to get any use out of the cat,

he’d have to start by getting it down from the kitchen cupboard.

But

no end of coaxing would bring the cat down from its vantage point – not even a

slice of premium ham. The man contemplated standing on a chair and dislodging

the cat or throwing something at it, but he really couldn’t be bothered.

Besides, it would be much more fun to get the cat to trust him and then see the

surprise in its furry little face when he took his penknife to it. The man made

his own dinner, ate it and went through to the sitting room to mark first-year

physics assignments, leaving a plate of ham out to see if the cat would come

down in his absence.

That night the man dreamt that he was walking through an unfamiliar landscape

of red and black. The landscape was constantly shifting and changing. One moment

he was walking along a mountain path, looking down into a valley of houses and

fields, next he was in a labyrinth of tunnels, the walls made of human bones

and skulls arranged in intricate patterns, one on top of the other. Somewhere

ahead of the man a fire burned, and light from it bounced around the bone

walls, bathing them in a warm glow and sending shadows flitting around the man.

Beside him walked Schrödinger the cat, watching him with a modicum of

curiosity, as if all this was familiar to the animal and it was merely

interested in what the man made of it all – interested, but not

that

interested.

As

the man approached the source of the flames, he became aware of the crackling

sound they made. The crackling became a scratching, and the scratching grew

louder until the man awoke. The scratching continued and the man realised that

it was coming from his wardrobe. The damned cat had somehow got into it and was

probably ruining his suits. He reached over to switch on his bedside lamp and

recoiled as his fingers touched fur. The man sat upright and the cat leapt off

the bedside table on which it had been sitting.

“Goddamn

you, Schrödinger!” The man switched on the lamp and glared at the creature now

sitting in the doorway. He swung his legs out of bed, but the cat had already

gone. The man closed his bedroom door and went back to sleep.

In the morning the cat was back on the kitchen cupboard, and the ham was

untouched on the plate where the man had left it the night before. The creature

obviously hadn’t eaten for a while and it had to be hungry. Either it was sick

or it had been trained not to eat anything other than cat food. The man

determined to buy some

Whiskas

on his way home from work.

But

the cat wouldn’t eat

Whiskas

, or

Meow Mix

or

Friskies

. It

wouldn’t drink milk or water and it wouldn’t eat cat biscuits. In fact, it was

a miracle that it was still alive. It was growing more emaciated by the day,

and its protruding ribs only served to make it look scruffier and uglier. For a

moment the man astonished himself by contemplating taking it to a vet, but

quickly shrugged off such an insane idea and decided to kill it. He placed a

kitchen chair next to the cupboard on which Schrödinger was perched, and went

to get the meat cleaver. Then the doorbell rang.

The

man put down the cleaver and went to answer the door. It was the teenage girl

from the house next door.

“I’m

sorry to bother you,” she said, “but I’m locked out of the house. I forgot to

take my keys this morning and my mum isn’t back till seven. A couple of workmen

followed me home from the high street and I don’t want to wait outside. Can I

hang out at yours until my mum gets back?”

The

man studied the girl’s short skirt and the way her blonde hair was pulled back

in a ponytail, revealing the curve where her neck met her shoulder.

“Sure,”

he told the girl and stood aside to let her in. He cast a quick glance around

the street. Sure enough, he saw two workmen loitering across the road, but they

quickly turned on their heels and disappeared. There was no one else around.

“Would

you like a cup of tea?” the man asked, leading the way to the kitchen.

“No

thanks. Have you got any coke?”

“Yes.”

The man got a coke from the fridge and handed it to the girl. “Would you like a

glass?”

“No

thanks.” The man indicated for the girl to take a seat. That was when they both

saw Schrödinger. It was standing on the kitchen table, tail twitching, staring

at the girl.

“Oh,

what a cute kitty!” cried the girl and moved towards the animal.

“Schrödinger,

what the hell are you doing?” The tone in the man’s voice stopped the girl in

her tracks. The man moved forward, ready to swipe the cat off the table, but as

he did so, the sharp pain in his head came, then went, and a voice near his ear

said, “Kill her!”

“What?”

exclaimed the man.

“What?”

asked the girl, staring at the man uncomprehendingly.

“Nothing,

honey, nothing.”

But

the voice came again, more persistent this time: “Kill her … now!”

The

man felt confused. He looked at the girl. Her tanned arms and legs looked so

inviting. A small artery in her neck was throbbing. The man found himself

wondering how far the blood from that artery would spurt and whether it would

reach the ceiling or just spatter the walls. He wondered whether the look of

surprise in her eyes would be like that of the kittens and puppies he had

dispatched to kitten and puppy heaven as a boy. He suspected that it would be

better – much better – than anything he had experienced before. His cock was

throbbing and he realised that the cat was staring at him, green eyes blazing,

its customary disdain replaced by a feral excitement.

The

artery in the girl’s neck was still throbbing. Her lips were cherry red and a

look of alarm was creeping over her face. She raised her hand to cover her

mouth and, as she did so, her top rode up a little and the man could see the

silver ring in her pierced belly button. As time seemed to stop then stretch

around the man, he noticed that the blue of the small gemstone on the ring

matched the colour of the girl’s eyes.

The

artery in the girl’s neck was throbbing, the man’s cock was throbbing, and now

a blood vessel in his head started to throb. The light in the kitchen seemed to

throb and then the whole world was throbbing – a glorious red throbbing,

pulsating, pounding. Then the meat cleaver was in the man’s hand and the look

of surprise in the girl’s eyes was better than the puppies and the kittens – it

was better than anything the man had experienced before, and the girl’s blood

was on the walls and on the ceiling and on the floor.

When the throbbing subsided, the man was sitting on the floor, his hands and

clothes covered in blood. He felt calm and he felt good. The cat was standing

beside him, face and whiskers stained red, frenziedly lapping up the girl’s

blood from the floor. The man stared at the animal in disbelief, but made no

move to stop it. Despite the blood on its snout, the cat seemed less dirty than

before: its fur seemed sleeker, it seemed somehow fatter and healthier, even

its tattered ear seemed to have grown back together.