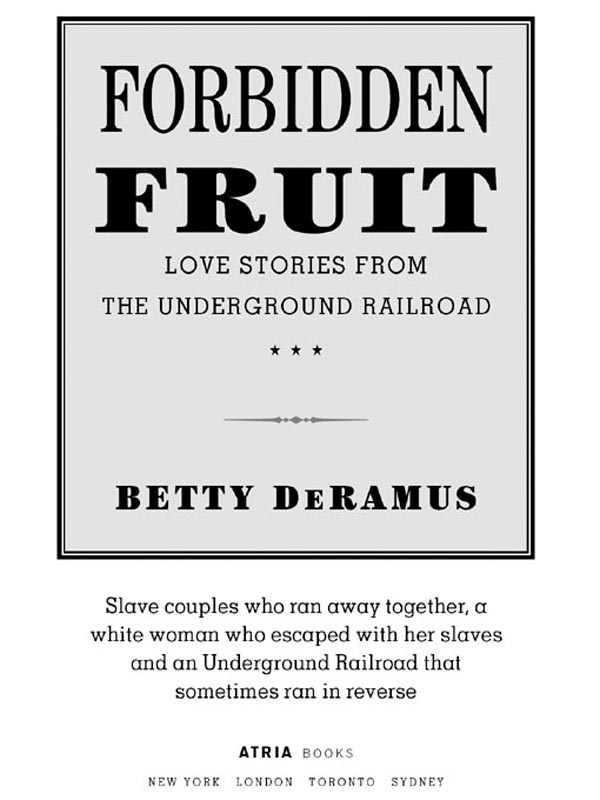

Forbidden Fruit

Authors: Betty DeRamus

1230 Avenue of the Americas

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 2005 by Betty DeRamus

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof

in any form whatsoever. For information address Atria Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas,

New York, NY 10020

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-1337-7

ISBN-10: 1-4165-1337-X

First Atria Books hardcover edition February 2005

Design by Nancy Singer Olaguera

ATRIA

BOOKS

is a trademark of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

To my mother, Lucille Richardson DeRamus, and my father, Jim (cq) Louis DeRamus, who,

during thirty-three years and nine months of marriage, stayed in love

I

owe many thanks to Rita Rosenkranz, my agent, who believed in me even when I didn’t;

my patient editor, Malaika Adero; researchers Dale Rich, Camille Killens and Cathy

Dekker of Detroit and Berkley; Katharine C. Dale, Iowa City, Iowa; Linda Worstell

of Sandy, Utah; Tom Gorden, Boston; Russell Magnaghi and Darlene Walch, Northern Michigan

University, Marquette, Michigan; Brigitte Burkett of Richmond, Virginia; Martina Kunnecke,

director of exhibits and technology, Kentucky Center for African American Heritage,

Louisville, Kentucky; Dr. Ronald Palmer, professor emeritus, George Washington University,

Washington, D.C.; Dr. Norman McRae, historian, Detroit; Arthur La Brew, musicologist

and historian, Detroit; Bryan Prince, historian, Buxton, Ontario, Canada; Alice Torriente,

Baltimore, Maryland; Joanne McNamarra, Louise Dougher and Deanne Rathke, Greenlawn-Centerport

Historical Society, Greenlawn, New York; Louis Hunsinger Jr. and Mamie Diggs, Williamsport,

Pennsylvania; Mary Neilsen, North Fairfield Museum, Ohio; Bonnie Mead, Huron County

Historical Society, Ohio; Amy Wilson, acting director, and Jason Harmon, education

coordinator, Chemung County Historical Association, Elmira, New York; Ralph Clayton,

Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore, Maryland; Pete Lesher, Chesapeake Bay Maritime

Museum, St. Michaels, Maryland; Jeanne Willoz-Egnor, Mariners’ Museum, Newport News,

Virginia; Clarence Still Jr., Linda Waller and C. Joyce Fowler of the Lawnside Historical

Society, Lawnside, New Jersey; Mary Davidson and Margo Brown of the Salt Spring Historical

Society, Saltspring Island, British Columbia, Canada; Calvin Murphy, Bear Lake, Michigan,

and Shelley Murphy, Charlottesville, Virginia, for information about their cousin,

Calvin Clark Davis; Bennie J. McRae Jr., Trotwood, Ohio; Larry O. Simmons, Detroit,

Michigan; Ronald Stephenson, Detroit, Michigan; Professor Kimberly Davis, Adrian,

Michigan; Sharon Rucker, Grand Rapids, Michigan, a descendant of Molly Welsh and Bannaka;

Marie Berry Cross and Jim Cross, Mecosta County, Michigan; the late Marguerite Berry

Jackson and Raymond Pointer, Morley, Michigan, descendants of Isaac and Lucy Berry;

and Berenice Easton, Greenlawn, New York, granddaughter of Samuel and Rebecca Ballton.

T

he author is grateful to those listed below for granting her permission to use the

following material. All possible care has been taken to trace ownership of material

and to make full acknowledgment. If any errors or omissions have occurred, they will

be corrected in subsequent editions if notification is sent to the publisher.

The Chemung County Historical Society for permission to use excerpts from the

Chemung Historical Journal,

June 1960 issue, pages 710–11.

Wayne State University Press for permission to use excerpts from

Copper Country Journal: The Diary of Schoolmaster Henry Hobart, 1863–1864,

ed. Philip P. Mason, © 1991 Wayne State University Press.

Ginalie Swaim, editor, the

Iowa Heritage Illustrated,

for permission to use excerpts from “The Desire for Freedom,” May 1929 issue of

The Palimpsest,

now known as the

Iowa Heritage Illustrated.

Mark Silverman, publisher, the

Detroit News,

for permission to use excerpts from the

Detroit News,

“Black Pioneers Tackle Northern Wilderness” (February 15, 2000) and “Duty, Not Race,

Defined War Hero” (February 5, 2002).

Marie Loretta Berry Cross and Jim Cross for permission to use material written by

family members.

T

his is a collection of love stories about slavery-era couples, some enslaved, some

free, most black, but a few interracial, who fought mobs, wolves, bloodhounds, bounty

hunters, bullets and social taboos to preserve their relationships. For both the black

couples and the interracial ones, lasting love was the forbidden fruit, the apple

no one was supposed to bite. Yet all of these couples insisted on leaping at life

and love, no matter what price they had to pay.

Many of these couples received help from the Underground Railroad, as it is commonly

known, a sometimes organized, sometimes informal and sometimes spontaneously assembled

network of people and places that sheltered fugitives. However, in most cases they

began their journeys alone or created their own networks, finding help whenever and

wherever they could.

I began collecting these stories after visiting a central Michigan town where I first

heard the story of a twenty-year-old white woman named Lucy Millard and a twenty-six-year-old

slave named Isaac Berry. In 1858, they ran away separately so they could meet and

marry in Canada. He traveled on foot and on the Underground Railroad while she rode

a real train.

In this collection you’ll also meet a young slave girl who travels inside a wooden

chest to meet her fiancé, a Canadian runaway who outlives five wives, a man who literally

carries his wife to freedom and a black man who trades his freedom for love.

These, however, are not simply stories about the past. Each one contains a lesson

for the present—a reminder of what once sustained people, what armored their spirits,

what preserved their communities and what inspired them to push on. A couple of these

stories, in fact, have the sweep of an epic, tracing the influence of a family tradition,

story or person through several generations.

My sources include descendants of runaway slave couples, unpublished memoirs, unpublished

school curriculum outlines, nineteenth-century newspaper articles, family reunion

publications and videotapes, slave narratives, Civil War pension records, census data,

slave schedules, books, magazine articles, photo exhibits, cookbooks and historical

museum monuments.

This is a book about people pursuing love and achievement in a time of hate and severely

limited opportunities. Though not all of these true tales end in triumph, they all

include hope, passion and the pursuit of joy.

3 The Special Delivery Package

4 The Man Who Couldn’t Grow a Beard

5 Even a Blind Horse Knows the Way

9 The Woman on John Little’s Back

Book II

Crossing the Color Line

The

Rebels

Love in a Time of Hate

J

oseph Antoine would have found the twenty-first century as baffling as ballet is to

a bulldog. He wouldn’t have understood married couples who split up before their wedding

flowers wilt or their new woks and washing machines lose their showroom shine. He

wouldn’t have understood why black marriage, as an institution, began dwindling so

drastically after 1940. He wouldn’t have understood why black children, who once could

count on honorary “aunts” and “uncles” on every plantation, now, in some cases, boil

their own oatmeal and tuck themselves into bed. Most of all he wouldn’t have understood

why, for some men, falling in love became a fatal flaw, the crack in a man’s smooth

chocolate-ice-cream cool.

For the love of a woman, Joseph Antoine sat in a jail cell, churning out letters that

explained how he wound up in the trap baited, set and sprung by his wife’s owner.

For the love of a woman, Joseph Antoine stood on an auction block to be sold like

a keg of bourbon or a hog.

For the love of a woman, Joseph Antoine signed away his freedom and became an indentured

servant, or temporary slave, for seven and a half years. His court petitions and records

document his struggle to hold on to his wife, no matter how large or even deadly a

price he was required to pay. However, his story of commitment to a slave-era marriage

is hardly unique.

But why would a free black man in the early 1800s open his heart so totally to a woman

he couldn’t legally marry? Wouldn’t a man born in one slave society and living in

another have learned to keep his emotions on ice, his affections scattered, his love

chopped and diced into small, easily swallowed chunks? Some slave owners certainly

believed this. In fact, many justified splitting up plantation couples by claiming

that slaves felt little pain at losing a mate and cared nothing about lasting relationships.

“Not one in a thousand, I suppose, of those poor creatures have any conception whatever

of the sanctity of marriage,” wrote the wife of an Alabama minister. American-style

slavery did indeed promote serial relationships, sex without commitment and the wholesale

production of babies for sale. All the same, slave families valued their kin and often

longed for the stability of legal relationships and families. In fact, during the

Civil War and immediately afterward, freedmen rushed to get married, round up lost

relatives and bring their women home from the fields. Between 1890 and 1940, a slightly

higher percentage of black adults than whites married.

Still, full-fledged romantic love—the kind of love Joseph Antoine felt—could lead

to heartbreak, particularly if a man had to stand by and watch his woman insulted,

beaten, overworked, raped, starved or sold away. In Louisiana, a slave named Hosea

Bidell was separated from his mate after twenty-five years of togetherness, and others

could tell similar stories. As a freeman informally married to a Southern slave woman,

Joseph Antoine was especially vulnerable, yet he never put any fences around his heart.

He had been born a slave on the hilly green main island of Cuba. It was a land where

gold-seeking Spanish conquerors armed with muskets, cannons, armor and steel swords

had nearly wiped out the native population with diseases, beatings, torture and harsh

work. They then brought in African slaves to work the plantations. Once the sugar

cane and tobacco industries based on slave labor took over the island’s economy, black

Cubans, slave and free, multiplied. However, despite the harshness of life on strength-sapping

sugar cane plantations and the deadly punishments for runaway slaves, Cuban blacks

made up a large part of both the skilled and unskilled labor pool on the island. By

the mid-eighteenth century, free black people, known as

negros horros,

were most of the island’s shoemakers, plumbers, tailors, carpenters and other tradesmen.

Moreover, slaves had certain basic rights, including the right to marry, stay with

their families, embrace the Catholic Church and receive religious instruction.

In the late 1700s, Joseph Antoine’s owner freed him. It’s not known why his owner

did this or even who his owner was. However, a Cuban slave could be freed for all

kinds of reasons, including identifying counterfeiters, exposing treason, denouncing

a virgin’s rape, avenging his owner’s murder or simply because his master wanted to

let him go. As a result, 41 percent of Cuba’s blacks were free by 1774.

In 1792, Joseph Antoine left Cuba, a land with dry and wet seasons, mahogany, ebony

and royal palm forests, and moved to Virginia, which, until at least 1860, was the

oldest and largest slave society in North America. Antoine was twenty-seven years

old, could read and write and carried papers that proclaimed his freedom. He never

explained why he decided to come to America—perhaps the smell of adventure drew him

or perhaps he simply wanted to start his life as a freeman in a place where he had

never been branded a slave.

It was the kind of mistake anyone could make.

Like Cuba, Virginia had thick forests, but there were no easily caught hogs or cattle,

no wild fruits to pinch from trees and, for someone like Joseph Antoine, little that

felt or tasted like freedom. In his native land, slaves had the right to personal

safety and the right to marry. In eighteenth-century Virginia, a man could kill his

slave without being guilty of a felony, slave marriages had no legal standing and

a host of laws squeezed, hemmed in and whittled away at the rights of free blacks.

Many whites, in fact, considered free blacks good for nothing except making slaves

think too much of themselves or inspiring them to run.

Until 1782, Virginia law made it nearly impossible for anyone to free a slave. Once

those restrictions fell, the number of free blacks in the state leaped from fewer

than three thousand to nearly thirteen thousand by 1790. Slaveholder Joseph Hill was

one of those who decided he wanted to free his slaves. In 1783, he wrote a will giving

his bondsmen their freedom upon his death because, he said, he felt that freedom was

the natural condition of mankind. Inspired by the Declaration of Independence, others

followed his lead. However, a year after Joseph Antoine’s arrival, Virginia began

turning off the tap. It passed a whole series of laws that set traps for free blacks

and slung nooses around their necks.

In 1793, Virginia prohibited free blacks from moving into the state. In 1800, it made

those who were there register. In 1806, newly freed blacks were ordered to leave the

state within twelve months or return to slavery. In 1819, the Virginia General Assembly

ruled that freedmen and slaves couldn’t meet in groups for educational purposes. In

1832, a year after Nat Turner’s bloody, Bible-bolstered raiders spread terror across

the countryside, the Virginia legislature clamped more restrictions on free blacks,

forbidding anyone to teach them to read and write. Black ministers lost their voices,

too: they could no longer preach in Virginia or help run a church. Under an 1838 law,

any free Negro who left the state to get an education couldn’t return to Virginia.

Frances Pelham, a free black Virginia wife and mother, once threatened to scald with

boiling water an official who came to snatch her family’s dog. Under Virginia law,

whites and slaves could own dogs, but free blacks couldn’t.

These were just a few of the traps and snares waiting for Joseph Antoine when he landed

in his new home, sweet Virginia, also known as the Old Dominion. Did he understand

at once the hurdles he faced? Or did it take a while for him to size up his situation

and realize its scope? Actually, despite Virginia’s hostility toward free blacks—much

of it springing from white fears that free blacks and slave laborers were stealing

their jobs—Joseph Antoine still might have led a fairly low-key, friction-free life.

The woman changed everything. Oh yes, she did.

She was a slave owned by a man named Jonathon Purcell, who was born in 1754 in Hampshire,

Virginia, now West Virginia. Antoine married her—or what passed for marriage in American

slave societies. Her name is not known, and no pictures of her or Antoine survive.

Maybe she was a black beauty with the kind of high-riding hips that could support

a bundle or rock a baby, Africa oozing from every pore. Or maybe she was a pale woman

with a slant to her eyes and a whisper of silk and cinnamon in her hair. Or perhaps

Antoine just looked into eyes the color of morning coffee and saw something that told

him that in this far-off place called Virginia he’d managed to find a home.

Joseph Antoine didn’t know it, but his love for his enslaved wife put him in all kinds

of danger, including the danger of giving her master a button he could push. Around

1796, Jonathon Purcell decided to do just that. He was about to move to the frontier

post at Fort Vincennes, Indiana, in the Northwest Territory. In 1787, the U.S. Congress

had established the Northwest Territory as free and declared that slavery there “save

in punishment for crime” would be prohibited. The territory included land that would

later be divided into the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin and Michigan.

However, some slavery still lingered in the region in 1796 and even later. In 1830,

the village of Vincennes, the oldest town in Indiana, contained 768 white males, 639

white females, 63 free black men, 63 free black females, 12 slave men and 20 slave

females. Still, Jonathon Purcell would have been fully aware that moving to free territory

would eventually deprive him of the services of Joseph Antoine’s wife. So he took

out an insurance policy guaranteed to keep her in bondage and make sure she wouldn’t

run: he appealed to her husband’s heart.

Antoine already had decided to accompany his wife to Vincennes. Knowing how much Antoine

loved his wife, her owner threatened to sell the woman in Spanish territory unless

Antoine, a freeman, signed papers making him an indentured servant for seven and a

half years. Purcell also demanded that Antoine’s wife sign an identical contract.

Indentured servitude was the seventeenth-century solution to America’s scarce labor

problem. Before sailing to America, immigrants signed contracts that spelled out the

terms of their service and their freedom dues. Skilled workers rarely served more

than three years, and others agreed to four or five. Seven was usually the maximum

number of years served. Typically, at the end of his term, an indentured servant received

freedom dues that might include tools, clothes, a gun and, in the first half of the

seventeenth century, fifty acres of land. The earliest blacks who came to America

were indentured servants, not slaves, pledging to work free for a specific period

of time to cover the cost of their transportation to this country. They were treated

more or less like poor whites bound by the same contracts and received money at the

end of their service. There is no record that Antoine and his wife were promised freedom

dues, land or any other compensation besides the right to stay together.

At first, Antoine refused to sign the indenture papers. Purcell forced the couple

into a room and locked the door. He promised that both Antoine and his wife would

be free at the end of their service. Finally, the couple agreed to sign the papers

and accompany Purcell to Vincennes, in the Indiana Territory, on the east bank of

the Wabash River among vineyards and peach, cherry and apple trees. Purcell’s brothers,

William and Edward, and their families came along, too, all of them Revolutionary

War veterans. Purcell became a prominent man in the Indiana Territory: in 1800, he

was appointed a justice of the Court of General Quarter Sessions of the Peace for

Knox County, Indiana, and a justice of the Court of Common Pleas.

Meanwhile, for seven years, Joseph Antoine and his wife labored on the Indiana frontier,

dreaming of a free future. Around 1803, as the couple neared the end of their service,

Antoine reminded Purcell of his promise. That’s when Purcell informed the Antoines

that they had misunderstood the agreement. Their term of service was for fifteen years

each, not seven and a half.

Before Antoine could absorb this shock, he heard a rumor that Purcell planned to sell

him and his wife to Manuel Lacey, a slave trader from St. Louis. The rumor hardened

into fact. Lacey took Antoine and his wife straight to the slave market in New Orleans

and sold them as slaves for life. Antoine managed to obtain an audience with Manuel

Juan de Salcedo, the last Spanish governor of Louisiana, who served until the territory

was transferred to France on November 30, 1803. After Antoine showed the governor

his freedom papers from Cuba, the governor, usually portrayed as a corrupt official

who tried to squeeze profits from his post, did the right thing. He released Joseph

Antoine and his wife from the sale. However, they feared that, under the law, Antoine’s

wife would remain a slave until the two of them had served out the full fifteen-year

terms of their indenture.

A legal noose still encircled their necks and they couldn’t seem to shake it off.

Lacey assured the couple he would treat them kindly while they served out the final

years of their contract. However, on the trip to St. Louis, they quickly saw that

they had, once again, stumbled into a trap. Lacey treated them so badly that the couple

decided they had only one move left—they would run. In 1804, they fled into Kentucky,

Antoine taking the name Ben. No doubt they hoped to reach Ohio or some other free

territory. However, Antoine’s wife, drained and exhausted, collapsed by the roadside.

While cradled in the arms of the man she loved, she died.

Despite what must have been profound grief, Antoine continued on to Louisville but

was soon captured by Davis Floyd, a slave driver hired by Lacey. After trying unsuccessfully

to sell Antoine, Floyd threw him into the Louisville jail. On September 19, 1804,

Antoine presented the first of a series of petitions to the Jefferson County Circuit

Court, spelling out his troubles and pleading for help.