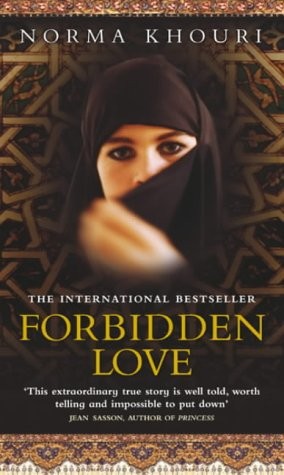

Forbidden Love

Authors: Norma Khouri

Forbidden Love by Norma Khouri

ISBN 1-86325-348-::

front t’OO’Vt’r image: zejti

NON-FICTION

Ins hook to tan rights d 9 “781863 “253482” Norma Khouri has had poems and short stories published in anthologies. As a result of the events recounted in Forbidden Love (which was written secretly in an Internet cafe), she was forced to emigrate to Athens. She now lives in Australia.

FORBIDDEN LOVE A BANTAM BOOK

First published in Australia and New Zealand in 2003 by Bantam.

Copyright (c) Norma Khouri, 2003

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry

Khouri, Norma. Forbidden love: a harrowing tale of love and revenge in Jordan.

ISBN 1 86325 348 3.

1. Murder Jordan. 2. Women Crimes against Jordan. 3. Love. 4. Revenge. 5. Honor. 6. Jordan Social life and customs. I. Title.

364.1523

Transworld Publishers,

a division of Random House Australia Pty Ltd

20 Alfred Street, Milsons Point, NSW 2061

http://www.random house.com.au

Random House New Zealand Limited 18 Poland Road, Glenfield, Auckland

Transworld Publishers,

a division of The Random House Group Ltd

61-63 Uxbridge Road, London W5 5SA

Random House Inc 1540 Broadway, New York, New York 10036

Typeset in 12.5/16 pt Bembo by Falcon Oast Graphic Art Ltd. Printed and bound by Griffin Press, Netley, South Australia

10 9 8 7 6 5

FORBIDDEN LOVE

A harrowing true story of love and revenge in Jordan

NORMA KHOURI

BANTAM BOOKS SYDNEY AUCKLAND TORONTO NEW YORK LONDON FORBIDDEN LOVE

Jordan is a place where men in sand-coloured business suits hold cell phones to one ear and, in the other, hear the whispers of harsh and ancient laws blowing in from the desert. It is a place where a worldly young queen argues eloquently on CNN for human rights, while a father in a middle-class suburb slits his daughter’s throat for committing the most innocent breach of old Bedouin codes of honour.

It is a place of paradox and double standards for men and women, for liberated and conservative. Modern on the surface, it is an unforgiving desert whose oases have blossomed into cities. But the desert continues to blow in. Streets are parched and stripped of flowers, trees or greenery-except for a rare grapevine in private patios and new steel and glass corporate towers reflect the tawny colours of the dunes. In their shadow, cafes are full of high-tech chatter, and young men in Jordan’s requisite tan jacket and Levis rub elbows with elders in dish-da shay the ankle-length dress shirt that is a vestige of the desert. Young women in veils view with envy the ‘modern’

girls sipping espresso, smoking, slim legs exposed to the knee. Unlike the Jordan River, no longer strong enough to flow down to Amman, the desert drifts up to the city’s boundaries. Like the sand that coats the streets after a wind storm, the Bedouin code is always encroaching on its urban streets. It permeates my family’s neighbourhood in Amman, dense-packed and tight-knit as a nomadic camp and filled with descendants of the original tribes. Its fierce and primitive code is always nagging at men’s instincts, reminding them that under the Westernizing veneer, they are all still Arabs. For most women, Jordan is a stifling prison, tense with the risk of death at the hands of loved ones. It is my home. I love its stark beauty, its sweep of history. And yet it may never be safe for me to return.

But let me set the stage for this story by giving some sense of my strange, conflicted nation. Bordered by Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Kuwait, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan sits at the beating geographic heart of the Arab world. A constitutional monarchy with King Abdullah Bin Hussein and Queen Rania presenting our modern face to the world, it is a small, predominantly Muslim country. Its capital, Amman, is home to a third of the nation’s people, as well as to a horde of historical, cultural and social riches. Beyond Amman, the Roman Pillars of Jerash, the Nabateen temples of Petra carved from canyons of pink stone that glow with magical light as the sun strikes at dawn and sunset, the Byzantine mosaics of Madaba, Mount Nebo, and Wadi Kharrar, the baptismal site of Christ, continue to lure travellers and pilgrims.

Jordan swaggers with pride at being a modern, technologically advanced, and rapidly democratizing nation (or so it would like the world to believe). But the process is often awkward and outdated. Amman did progress dramatically in the final decade of the twentieth century. New hotels and banks sprang up on virtually every city street; computers equipped with the latest technology were installed in offices and homes everywhere, linking Jordanians to the larger world. Cell phones, pagers, and portable faxes are now as common as a pair of sunglasses. The government has spent millions annually to attract foreign investors, improve commerce, and increase tourism.

Yet a few hours’ drive from this modern metropolis is a world that existed before Christ. Spend a day in Wadi Rum exploring the Nabateen and Thamudic cave drawings with the Bedouins, barter for their jangling jewellery or share tea in their goat-hair tents, and you’ll feel as if you’ve gone back in time. Jordan is one of a very few countries where the present and past live in tense and dynamic co-existence. It is a country that unfurls banners of welcome to the future, yet holds tenaciously to its ancient roots and traditions.

For Jordanian women progress has been slower coming than for men. We are now allowed to study any subject we want as long as the men in our families our fathers, brothers, or, if married, husbands give us their permission. And, compared with women in most Muslim countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, women in Jordan have more freedoms and privileges -access to a full education, the right to drive cars, and, as of 1989, to vote, provided, of course, the male heads of our households approve. Yes, Jordan can claim many women doctors, but partly because a woman dare not be seen by a male doctor for fear of the kind of gossip that could threaten her life. And mostly the women who have the freedoms and privileges come from very wealthy and modern families, families that do not pay such attention to neighbourhood rumours.

In a country that boasts of its modernity, a woman’s decisions are still made by men. A man must authorize everything in her life, from the person she marries to her wardrobe. It’s a male-dominated world with very limited and controlled ‘freedoms’ for women.

So while men celebrate their country’s progress, women still pray that their silent cries will be heard. Even for the women who, on the street, look liberated-like me, in my loose skirts and trousers and my hair swinging free of the veil-the risks of rebelling are so high that, while we boil inside, we obey. We cling to the fading hope that someday we’ll be released from this prison, not really believing that we can be the agents of our own freedom. Controlled by the fear generations of male dominance has instilled in us, a fear reinforced by our mothers, our only option seems to be to live carefully within the rules, regulations, and beliefs of the men who govern us. We absorb from birth that breaking the code is very, very dangerous. And yet there are a few rare women who risk their lives to try. The whispers they hear are not from the desert, but from the winds of change.

The cluttered break

room in the back of ND’s Unisex Salon was not much to look at. Twenty years of scuff marks marred the once-white walls, and the tile floors, which had once been warm earth beige, were now a dull yellow-grey. The scruffy brown couch to the right of the door looked like a battered old man, pockmarked by time. But my best friend, Dalia, and I knew the room’s true value; to us it was a haven, a sanctuary, the only place where we had the privacy and freedom to share our secrets, hopes, dreams, fears, and disappointments.

That couch was the same one we’d sat on at the age of thirteen when we pledged that nothing and no one would ever destroy our friendship. We were like sisters, born a couple of months apart in 1970. Living as close neighbours in the Jebel Hussein district of Amman, we met at a neighbourhood park when we were three and, almost instantly, were inseparable. We each had four brothers and very strict parents. And, despite the fact that we were from different religions-her family was strict Muslim, while mine was Catholic as we grew up we faced similar obstacles that only strengthened the sisterly bond between us.

Though Jordan is a nation of rich and poor-the rich living in million-dollar villas and the poor in refugee camps-our families were part of the comfortable middle class that lived in houses handed down through their families for generations, and fathers who worked at respectable jobs mine had his own contracting business, Dalia’s was an accountant for a large insurance company. But we were not of the class that skimmed the cream of opportunities for women the elite who automatically sent their daughters to universities and abroad to live and study. Our parents never showed a hint of ambition for us, beyond marriage. By the time we entered our teenage years, we’d decided that we could forge the best future for ourselves by finding a way to stay together. At fifteen, we discovered that Jordanian women were allowed to own and operate beauty parlours, one of the few careers open to them. Higher dreams didn’t seem possible. And Dalia and I believed that having our own business would guarantee that we could remain together. So, armed with a plan, we started taking the necessary steps to set up our business.

Our first move was to assure our parents that we were not college material. We easily maintained “C’ averages, convincing them that this was the best we could do. In a country where a man’s education carries more weight that a woman’s, our lacklustre performance did not worry either set of parents. Next, we suggested that we enrol in beauty school and, given our bleak college prospects, our families did not object in fact they encouraged us to go. So, at eighteen, Dalia and I learned our trade. And, after finishing school and working at several places, we were able to complete our final step. Although we didn’t see it at the time, we were already using one of the few

powers Jordanian women have: to bend their intelligence and imagination to plotting and planning to outwit men to get what they wanted. We would become masters. It didn’t occur to us that the effort we spent on conspiring and manipulation might have been used to turn us into doctors or software designers. Achievement was tricking the men who controlled our lives; as we saw it, it was survival in an unequal world.

“If we keep complaining about working at this salon, I’m sure OUR fathers will agree to let us open our own place, if only to shut us up. My father seems ready to agree now. How about yours?” Dalia asked me one day, her eyes betraying a hint of conspiratorial glee.

“Mine’s getting tired of the complaints. But we better be careful; they could decided that we should stop working and stay at home. I keep telling them that we love the work, we just hate the working conditions.” I laughed.

The too, and I think they’ll go for it. Look at it from their point of view, they’ll have an easier time keeping an eye on us this way.” Until we were safely married and under the thumb of our husbands, we’d be watched every day, every hour, by our fathers and brothers.

In the end, we persuaded our parents to invest a small fortune in our salon. Our idea was to renovate a portion of a two-storey building owned by my father. The old, stone-fronted structure, which was close to both of our homes, had not been used for ten years, when it served as a warehouse for my father’s contracting business. Neglected, covered with graffiti, and boarded up, it was destined for the wrecking ball until our plan salvaged it. In return for the use of the ground floor and as payment for the construction work my father and brothers did, we’d pay a monthly rent. To save some masaree (money), the break room was the only part of the salon we didn’t modernize; it stayed as dingy as it was. But, behind its closed doors, it was ours.

We were going to be daring and provide a service no other salon in Amman seemed to be offering: we would cater for both men and women. As long as we were well watched and chaperoned, there was no prohibition against it.

We held the grand opening of ND’s Unisex Salon in May 1990. The stone facade had been removed and a glass front put in its place. To us, the interior had been transformed into a mini-palace. A large crystal chandelier hung from the high, vaulted ceiling and the walls were mirrored, giving the illusion that the room was double its actual size. The mirrors reflected the chandelier’s many bulbs, bringing light to every corner of the shop. A high marble counter ingeniously hid our desk and separated the reception area from our workstations, each equipped with all the top styling tools. To us, this salon was more than just a dream come true, it made us feel invincible and powerful. Our modest little enterprise had turned us into professionals, entrepreneurs-we’d created our own niche. Though we had to some extent designed our own cage, it was better that