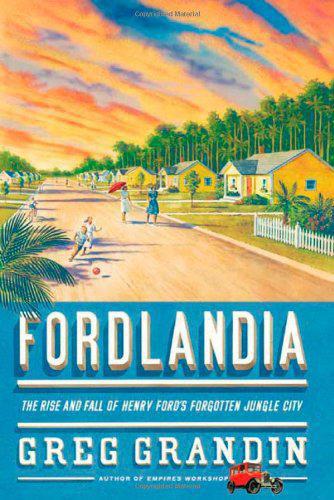

Fordlandia

Authors: Greg Grandin

Tags: #Industries, #Brazil, #Corporate & Business History, #Political Science, #Fordlândia (Brazil), #Automobile Industry, #Business, #Ford, #Rubber plantations - Brazil - Fordlandia - History - 20th century, #History, #Fordlandia, #Fordlandia (Brazil) - History, #United States, #Rubber plantations, #Planned communities - Brazil - History - 20th century, #Business & Economics, #Latin America, #Planned communities, #Brazil - Civilization - American influences - History - 20th century, #20th Century, #General, #South America, #Biography & Autobiography, #Henry - Political and social views

ALSO BY GREG GRANDIN

Empire’s Workshop:

Latin America, the United States,

and the Rise of the New Imperialism

The Last Colonial Massacre:

Latin America in the Cold War

The Blood of Guatemala:

A History of Race and Nation

FORDLANDIA

FORDLANDIA

The Rise and fall of Henry Ford's Forgotten Jungle City

Greg Grandin

Metropolitan Books

Henry Holt and Company, LLC

Publishers since 1866

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10010

Metropolitan Books

®

and ®

®

are registered trademarks of

Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

Copyright © 2009 Greg Grandin

All rights reserved.

Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd.

“DEEP NIGHT”

RUDY VALLEE, CHARLIE HENDERSON

© 1929 WARNER BROS. INC. (Renewed)

Rights for the Extended Renewal Term in the United States controlled by WB MUSIC CORP. and WARNER BROS. INC.

This arrangement © WB MUSIC CORP. and WARNER BROS. INC.

All Rights Reserved

Used by permission from ALFRED PUBLISHING CO., INC.

“RAMONA”

Music by MABEL WAYNE Words by L. Wolfe Gilbert

© 1927 (Renewed 1955) EMI FEIST CATALOG INC.

All Rights Controlled by EMI FEIST CATALOG INC. (Publishing) and ALFRED PUBLISHING CO., INC.

All Rights Reserved

Used by permission from ALFRED PUBLISHING CO., INC.

“Santarém” from

The Complete Poems 1927–1979

, by Elizabeth Bishop. Copyright © 1979, 1983

by Alice Helen Methfessel. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Grandin, Greg, 1962–

Fordlandia : the rise and fall of Henry Ford’s forgotten jungle city / Greg Grandin.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-8236-4

ISBN-10: 0-8050-8236-0

1. Fordlândia (Brazil)—History. 2. Planned communities—Brazil—History—20th century. 3. Rubber plantations—Brazil—Fordlándia—History—20th century. 4. Ford Motor Company—Influence—History—20th century. 5. Ford, Henry, 1863–1947—Political and social views. 6. Brazil—Civilization—American influences—History—20th century. I. Title.

F2651.F55G72 2009

307.76'8098115—dc22

200804964

Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets.

First Edition 2009

Designed by Meryl Sussman Levavi

Maps by Jeffrey L. Ward

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To Emilia Viotti da Costa

Why, though, did we need a Mahagonny?

Because this world is a foul one.

—BERTOLT BRECHT

The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION: Nothing Is Wrong with Anything

PART I: MANY THINGS OTHERWISE INEXPLICABLE

4: That’s Where We Sure Can Get Gold

13: What Would You Give for a Good Job?

17: Good Lines, Straight and True

21: Bonfire of the Caterpillars

EPILOGUE: Still Waiting for Henry Ford

FORDLANDIA

INTRODUCTION

NOTHING IS WRONG WITH ANYTHING

JANUARY 9, 1928:

HENRY FORD WAS IN A SPIRITED MOOD AS HE toured the Ford Industrial Exhibit with his son, Edsel, and his aging friend Thomas Edison, feigning fright at the flash of news cameras as a circle of police officers held back admirers and reporters. The event was held in New York, to showcase the new Model A. Until recently, nearly half of all the cars produced in the world were Model Ts, which Ford had been building since 1908. But by 1927 the T’s market share had dropped considerably. A half decade of prosperity and cheap credit had increased demand for stylized, more luxurious cars. General Motors gave customers dozens of lacquer colors and a range of upholstery options to choose from while the Ford car came in green, red, blue, and black—which at least was more variety than a few years earlier when Ford reportedly told his customers they could have their car in any color they wanted, “so long as it’s black.”

1

From May 1927, when the Ford Motor Company stopped production on the T, to October, when the first Model A was assembled, many doubted that Ford could pull off the changeover. It was costing a fortune, estimated by one historian at $250 million, because the internal workings of the just-opened River Rouge factory, which had been designed to roll out Ts into the indefinite future, had to be refitted to make the A. Yet on the first two days of its debut, over ten million Americans visited their local Ford dealers to inspect the new car, available in a range of body types and colors including Arabian Sand, Rose Beige, and Andalusite Blue. Within a few months, the company had received over 700,000 orders for the A, and even Ford’s detractors had to admit that he had staged a remarkable comeback.

2

The New York exhibit was held in the old Fiftieth Street Madison Square Garden, drawing over a million people and eclipsing the nearby National Car Show. All the many styles of the new model were on display at the Garden, as was the Lincoln Touring Car, since Ford had bought Lincoln Motors six years earlier, giving him a foot in the luxury car market without having to reconfigure his own factories. But the Ford exhibit wasn’t really an automobile show. It was rather “built around this one idea,” said Edsel: “a visual demonstration of the operation of the Ford industries, from the raw materials to the finished product.” Visitors passed by displays of the manically synchronized work stations that Ford was famous for, demonstrations of how glass, upholstery, and leather trimmings were made, and dioramas of Ford’s iron and coal mines, his blast furnaces, gas plants, northern Michigan timberlands, and fleets of planes and ships. A few even got to see Henry himself direct operations. “Speed that machine up a bit,” he said as he passed a “mobile model of two men leisurely sawing a tree, against a background of dense forest growth.”

3

Though he was known to have opinions on many matters, as Henry Ford made his way through the convention hall reporters asked him mostly about his cars and his money. “How much are you worth?” one shouted out. “I don’t know and I don’t give a damn,” Ford answered. Stopping to give an impromptu press conference in front of an old lathe he had used to make his first car, Ford said he was optimistic about the coming year, sure that his new River Rouge plant—located in Ford’s hometown of Dearborn, just outside of Detroit—would be able to meet demand. No one raised his recent humiliating repudiation of anti-Semitism, though while in New York Ford met with members of the American Jewish Committee to stage the “final scene in the reconciliation between Henry Ford and American Jewry,” as the Jewish Telegraphic Agency described the conference. Most reporters tossed feel-good questions. One wanted to know about his key to success. “Concentration on details,” Ford said. “When I worked at that lathe in 1894”—the carmaker nodded to the machine behind him—“I never thought about anything else.” A journalist did ask him about reports of a price war and whether it would force him to lower his asking price for the A.

“I know nothing about it,” replied Ford, who for decades had set his own prices and wages free of serious competition. “Nothing is wrong with anything,” he said, “and I don’t see any reason to believe that the present prosperity will not continue.”

4

FORD WANTED TO talk about something other than automobiles. The previous August he had taken his first airplane ride, a ten-minute circle over Detroit in his friend Charles Lindbergh’s

Spirit of St. Louis

, just a few months after Lindbergh had made his historic nonstop transatlantic trip. Ford bragged that he “handled the stick” for a little while. He was “strong for air travel,” he said, and was working on a lightweight diesel airplane engine. Ford then announced that he would soon fly to the Amazon to inspect his new rubber plantation. “If I go to Brazil,” he said, “it will be by airplane. I would never spend 20 days making the trip by boat.”

5

Ford didn’t elaborate, and reporters seemed a bit puzzled. So Edsel stepped forward to explain. The plantation was on the Tapajós River, a branch of the Amazon, he said.

Amid all the excitement over the Model A, most barely noted that the Ford Motor Company had recently acquired an enormous land concession in the Amazon. Inevitably compared in size to a midranged US state, usually Connecticut but sometimes Tennessee, the property was to be used to grow rubber. Despite Thomas Edison’s best efforts to produce domestic or synthetic rubber, latex was the one important natural resource that Ford didn’t control, even though his New York exhibit included a model of a rubber plantation. “The details have been closed,” Edsel had announced in the official press release about the acquisition, “and the work will begin at once.” It would include building a town and launching a “widespread sanitary campaign against the dangers of the jungle,” he said. “Boats of the Ford fleet will be in communication with the property and it is possible that airplane communication may also be attempted.”

6