Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937-1945 (28 page)

Read Forgotten Ally: China's World War II, 1937-1945 Online

Authors: Rana Mitter

As the Germans left, they made sure the roof of the train coach transporting them sported a prominent German flag, complete with swastika. This was a wise precaution, as Wuhan was already being subjected to serious aerial bombardment. The Japanese were beginning the campaign to capture the city, and some 800,000 Chinese troops had been gathered to oppose them. But the Yellow River floods made it impossible for the Japanese to approach the city from the north. Instead, they decided to use the navy to approach the city along the Yangtze River, supported by some nine divisions of troops. The Chinese fought with immense bravery, but their defenses were simply too weak to resist the pounding from the technologically advanced Japanese navy. They had only one welcome element of external assistance: Soviet pilots flying aircraft purchased from the USSR as part of Stalin’s plan to keep China in the war against Japan. (Between 1938 and 1940 some 2,000 pilots would offer their services to China.)

18

Between June 24 and 27, Japanese bombers furiously pounded the fortress at Madang, on the banks of the Yangtze, until it surrendered. A month later, on July 26, the Chinese defenders abandoned the city of Jiujiang (250 kilometers southeast of Wuhan), whose population was then subjected to a spree of murder and rape by the invaders.

The news of Jiujiang’s terrible fate stiffened military resolve. So did a highly critical address that Chiang gave to his troops on July 31. “Our achievement in our first year has been to bog down the Japanese,” he declared, pointing out that if Wuhan were lost, the country would essentially be split into north and south halves, which would cause great complications for moving men and supplies across the country. But Wuhan would also be “a great spiritual loss,” since the place had such strong connections to “revolutionary history.” The world’s sympathy for China’s case was growing, Chiang assured his listeners, and as people became aware of Japanese atrocities, the invaders’ reputation would suffer. However, Chiang was deeply concerned about the behavior of the Chinese troops. Men were not under the control of their officers; this was “the suicidal act of a doomed country.” Raiding the population would destroy the trust between citizens and the military. “Not only should you not steal,” Chiang declared, “you should be giving things

to

the people.” Commanders must stay at their posts; he reminded his listeners that the commander who had let Madang fall had been shot. Chiang’s message was aimed at the officers in particular. Unlike in Shanghai, he pointed out, there were proper air-raid shelters in Wuhan, but “we shouldn’t just jump into them and abandon our men!” or behave as some officers had in Xuzhou when they left their troops behind. If officers did not show loyalty, they could expect none in return.

19

The pep talk—along with the feeling that the army was making a desperate last stand—may have had some effect. The Japanese then had to fight much harder to advance up the Yangtze in August. Under General Xue Yue, some 100,000 Chinese troops pushed back Japanese forces at Huangmei. At the fortress of Tianjiazhen, thousands of men fought until the end of September, with Japanese victory assured only with the use of poison gas. Yet even now, top Chinese generals seemed unable to work with each other. At Xinyang, Li Zongren’s Guangxi troops were battered to exhaustion. They expected that the troops of Hu Zongnan, another general close to Chiang Kai-shek, would relieve them, but instead Hu led his troops away from the city and the Japanese captured it without having to fight. The capture of Xinyang gave the Japanese control of the Ping-Han railway, which spelled the endgame for Wuhan.

20

Chiang once again spoke to the troops defending the city. Knowing how desperate the situation was, he combined encouragement with an acknowledgment that the city might soon be lost. Although Wuhan was a city well connected to the outside world because of its large foreign population, the army must not expect any foreign assistance. Therefore, if it became necessary to leave Wuhan, they should have a proper plan for doing so. Chiang went on to specify which routes they should take. He then touched on one of the most affecting subjects possible: the disastrous retreat from Nanjing in December of the previous year, where “foreigners and Chinese alike had already turned it into an empty city.” The soldiers had been tired and too few in number. “So why did I order that it should be defended?” Chiang said he had asked the soldiers at Nanjing to “sacrifice themselves for the capital and for Sun Yat-sen’s tomb,” and they had “looked upon death as if it were just like going home.” If the army had retreated, Chiang declared, it would have been the worst shame in five thousand years of their history. The loss of Madang, too, had been a humiliation. Now, by defending Wuhan, “we avenge our comrades and wash away our shame.” Otherwise, Chiang said, “we cannot face our martyrs, or our own consciences.”

21

In giving this explanation Chiang had both to rewrite the past and build up political capital for the future. In this version of recent history, Nanjing

had

been defended to the death; it was the loss of the city, not the performance of the soldiers there, that caused the “shame.” In fact, Tang Shengzhi’s troops had fought hard for two days, but they had not been there when the Japanese arrived to overrun the city and kill and rape its citizens. By stressing the heroic element of the defense of Nanjing, and ignoring the story’s less creditable end, Chiang made it a scene of “martyrdom” that could inspire his troops for their last stand at Wuhan. At the same time, he had to make it clear that the defense of Wuhan would not be a defense to the death. It was a very difficult tightrope to walk. It must have helped that Chiang had a gift for self-deception; having constructed this version of the truth, he probably believed it quite sincerely.

Mao Zedong, observing the situation from his far-off base at Yan’an, agreed strongly that Chiang should not defend Wuhan to the death. “Supposing that Wuhan cannot be defended,” he wrote in mid-October, as the Nationalists made their last stand at the city, “many new things will emerge in the situation of the war.” Among these would be the continued improvement of the relationship between the Nationalists and the Communists, a more intense mobilization of the population, and the expansion of guerrilla warfare tactics. “The purpose of the struggle to defend Wuhan is to drain the enemy, on the one hand, and win time, on the other,” Mao continued, “so that the work in the whole country will make progress, and not a last-ditch defense of a strong point.” In a long war of resistance, it was quite “permissible” to give up certain strongholds temporarily so as to be able to sustain the wider struggle.

22

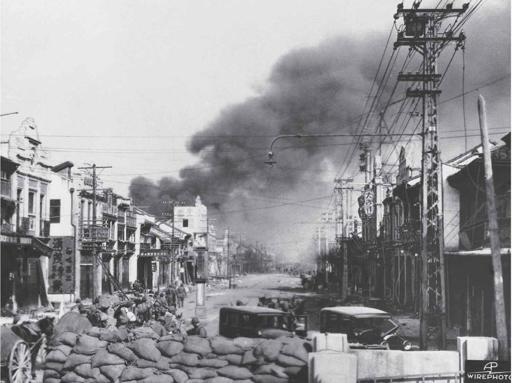

Scenes from Shanghai in October 1937 were now repeated, nearly a year later, in Wuhan. The government made frantic moves to ship the most important industrial plant upriver before the Japanese reached the city. As he had done in Nanjing, Chiang remained in command until the very last day. On October 24, Wuhan was unusually cold, and snow was falling on the city. Chiang called his senior officers and told them to depart. “You must go first,” Chiang told them, “I’ll leave soon after.” That evening, at ten o’clock, Chiang and his wife Meiling traveled to the city’s airfield. The weather had turned cold and snow was falling. The Chiangs’ airplane was delayed, so after some confusion, they boarded a civilian aircraft and left for Hengyang, 450 kilometers south of Wuhan. As they were leaving, guns sounded and Wuhan burned. They had departed just in time. On October 25, 1938, the city was surrounded on all sides, and fell to the forces of the Imperial Army.

23

There was one further tragic consequence of Chiang’s hasty judgment that the Japanese would not only take Wuhan, but swiftly drive further inland. He decided that the city of Changsha, to the south in Hunan, was vulnerable, and gave the impression (if not a direct order) that the city should be burned to the ground to prevent it falling to the enemy. Local officials consequently set fire to Changsha, and it burned for two days. But the Japanese did not reach the city: they stopped nearly 80 kilometers away, at Lake Dongting. Chiang denied responsibility for the destruction, but in reality it was his command that had led his subordinates (some of whom were then executed) to act.

24

All eyes now turned to the new center of resistance, the temporary capital at Chongqing. Chiang’s “Free China” now meant Sichuan, Hunan, and Henan provinces, but not Jiangsu or Zhejiang. The east of China was definitively lost, and along with it China’s major customs revenues, the country’s most fertile provinces, and its most advanced infrastructure. The center of political gravity moved far to the west, into country that the Nationalists had never controlled and where everything was unfamiliar and unpredictable, from topography to dialects to diets. On the map, it might have looked as if much of China was still under Chiang’s control. But vast swathes of the north and northwest were very lightly populated; the bulk of China’s population was in the east and south, where the Nationalists had either lost control or held onto it only very precariously. In the north, meanwhile, the Japanese and the CCP were in an uneasy stalemate. Mao’s army could make it impossible for the Japanese to hold the deep countryside, far from the railway tracks that enabled them to transport hundreds of thousands of men into China’s interior. But the Communists could not defeat the occupiers.

In the dark days of October 1938, fifteen months after war had broken out, one fact remained constant. Repeatedly, observers (Chinese businessmen, British diplomats, Japanese generals) had predicted that each new disaster must surely see the end of Chinese resistance and a swift surrender, or at least a negotiated solution in which the government would have to accept yet harsher conditions from Tokyo. But even after the defenders had been forced from Shanghai, from Nanjing, and from Wuhan, despite the terrifying might that Japan had brought to bear on the Chinese resistance, and despite the invader’s manpower, technology, and economic resources, China was still fighting. Yet it was fighting alone.

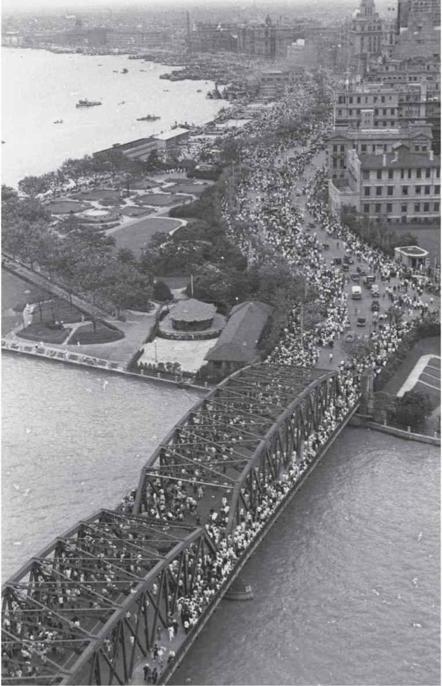

Refugees stream across the Garden Bridge, Shanghai, August 18, 1937. Just six weeks previously, war had broken out suddenly in North China.

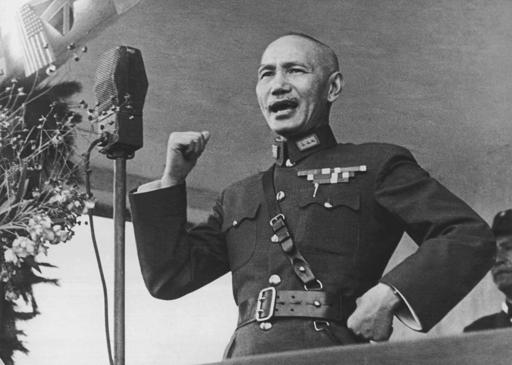

Chiang Kai-shek, thrust into the role of war leader, broadcasting in 1937.

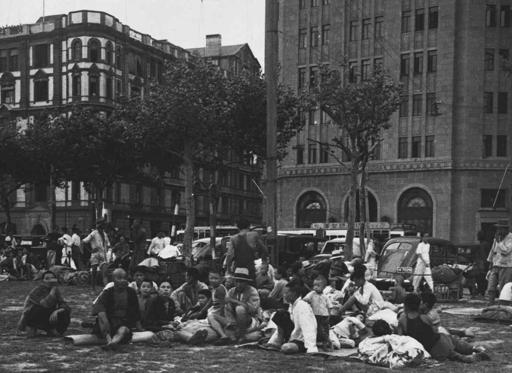

Refugees on Shanghai’s Bund, 1937. Even neutral zones in the city were flooded with Chinese desperate to escape the Japanese invasion.