Forgotten Man, The (34 page)

Read Forgotten Man, The Online

Authors: Amity Shlaes

Tags: #United States, #History, #20th Century, #Comics & Graphic Novels, #Nonfiction

“T

HIS IS A LOT OF MONEY FOR A COUPLE OF

I

NDIANA FARMERS TO BE KICKING AROUND

,”

Willkie

joked as he finally gave up and signed over Tennessee Power to

David Lilienthal

and the TVA (

below

) [B

ETTMANN

/CORBIS]. Meanwhile, Americans turned away from Roosevelt and toward other leaders to uplift them: one was

Father Divine

, a charismatic preacher who tilted with Roosevelt over lynching law (

above

) [AP I

MAGES

]. The puttering alcoholic

Bill Wilson

(

right

) created an intriguing new kind of therapy—the self-help group [AP I

MAGES

].

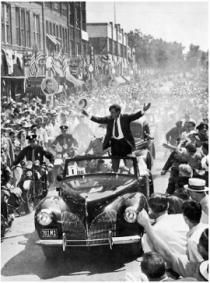

“W

HOSE FORGOTTEN MAN

?” “Is it enough for the free and able-bodied man to be given a few scraps of cash… is that what the forgotten man wanted us to remember?” asked

Wendell Willkie

in his acceptance speech after the Republican nomination in 1940. Americans crowded the streets of Elwood, Indiana. [T

HE

G

RANGER

C

OLLECTION

, N

EW

Y

ORK

]

The tabloid was correct. The case did indeed mean death for the NRA. By mid-June, thousands of employees in Washington received their last pay. The codes began to fade, even though there were some vehement protestors, mostly among larger firms. David Lilienthal’s appliance sales arm, the EHFA, could no longer operate under Lilienthal at the TVA; the executive order was null. For Lilienthal,

Schechter

was a signal of a tough road ahead. The TVA was already beset by dozens of lawsuits and injunctions; more were to come, and Lilienthal was not sure how he could handle them all. Willkie and his fellow power executives hoped that now they might manage to kill the dread utilities legislation, or at least alter it so that it was no longer a death sentence.

Roosevelt, who knew Brandeis less well than Frankfurter did, was surprised that the justice had gone along: “What about old Isaiah?” he asked, using his nickname for Brandeis. The president was furious. In a press conference a few days later at Hyde Park, he and Eleanor sat together before reporters. Eleanor was knitting a blue sock. Marion Frankfurter, Felix’s wife, was also in the room. Roosevelt castigated the press and the court. The NRA and the Humphrey case, as well as Frazier-Lemke’s repudiation, were all getting in the way of a change that must happen in the United States. What were the justices thinking, interpreting the Commerce Clause this way? They were, he told the reporters, going back to “the horse and buggy age.”

Still, the hour was that of the victors, who now knew that while Roosevelt’s voice mattered, theirs did too. At 15 Broad Street in New York, Frederick Wood celebrated—his wife had given him a miniature chicken coop housing two cotton hens and six chicks, which stood on his desk. Wood declared that with this case the justices had finally been “going at the fundamentals” of New Deal law. Heller celebrated too. He told the papers that

Schechter

showed that “the humblest individual receives the utmost protection under our form of government.” “Nine to nothing,” the Schechter brothers were heard to be repeating to the media at Heller’s offices at 51 Chambers Street. “We always claimed that the code authority attempted to make us the ‘goat,’” they announced in a statement to the press. Meanwhile,

the papers reported that some 500 cases against people charged with breaking NRA codes were now to be dropped.

The Schechters were concerned about the cost of the suit. But gratification was also theirs. Mrs. Joseph Schechter of 257 Brighton Beach Avenue displayed to the press a poem, titled “Now That It’s Over.”

No More excuses

To hide our disgrace

With pride and satisfaction

I’m showing my face.

For a long long time

To be kept in suspense

Sarcastic remarks made

At our expense.

I’m through with that experience

I hope for all my life,

And proud again to be,

Joseph Schechter’s wife.

Her cheerful mood accorded with that of the country. The Dow now staged its longest rally since Hoover had first lifted the beneficent hand.

July 1935

Unemployment (July): 21.3 percent

Dow Jones Industrial Average: 119

SHORTLY AFTER

SCHECHTER

, around the time of the “horse and buggy” press conference, a little-noticed event took place at the White House. Felix Frankfurter moved in.

The arrival of Frankfurter signaled a shift in Roosevelt’s outlook. He was tired of utopias, he now decided. They had not necessarily helped the economy. The hope that experiments like the NRA would bring full recovery had not proven valid. Roosevelt had played around with economics, and economics hadn’t served him very well. He would therefore give up on the discipline and concentrate on an area he knew better, politics.

The president formulated a bet. If he followed his political instincts, furiously converting ephemeral bits of legislation into solid law for specific groups of voters, then he would win reelection. He would focus on farmers, big labor, pensioners, veterans, perhaps women and blacks. He would get through a law for pensioners, and

one for organized labor, with the aid of Frances Perkins and Robert Wagner. Rex Tugwell would take care of the poor and homeless of the countryside—Tugwell was to have a staff of more than 6,000, $91 million, and options on ten million acres of land, all to try out suburban and rural resettlement. There was also $2.75 million for Dutch elm disease in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

If the politics was right, the wager said, the economy would follow suit and he could take credit for the rally himself. Indeed, he would

deserve

the credit. This attitude was the sort that William James, the philosopher at Roosevelt’s own Harvard, had written about in his famous essay “The Will to Believe”—if you had faith in an outcome, you could help to make that outcome occur. Frankfurter made a good audience, and suddenly, with Frankfurter as his partner, he had a surer sense of the way to go. The next two years would yield the results of the first part of that bet. The outcome in the second question would emerge definitively only later in the 1930s.

For a man eighteen months away from an election, the plan made sense. Roosevelt had Congress behind him, and he had his agencies, even if he did not have the courts. He could use his authority to win the votes—or lose the authority. After all, he had challengers advocating more radical programs than his. Huey Long in the Senate had his evangelizer, Gerald L. K. Smith. Long’s “Share Our Wealth” program promised senior pensions, free higher education, and employment for all. Francis Townsend, a doctor, had built a national movement with his own pension blueprint, the Townsend Plan. And Father Coughlin, the radio voice, had turned against the president. On May 22, just before the

Schechter

opinion came down, Roosevelt received what must have seemed a nearly equal blow in the news that Coughlin pulled 23,000 into Madison Square Garden to attack FDR. Coughlin assailed the “Morgans, Baruchs and Warburgs,” little caring—perhaps it didn’t matter—for Warburg’s battle with Roosevelt. Coughlin argued that capitalism should now be “constitutionally voted out of existence.” Roosevelt thought a lot about Coughlin, for Coughlin, with ten million listeners, was the superstar

of Roosevelt’s own medium, the airwaves:

Fortune

in 1934 had said that Coughlin was “just about the biggest thing that ever happened to radio.”

To preempt the demagogues, Roosevelt had to prepare his new legislation so that it pleased the same force that sealed the fate of the NRA: Brandeis. This was one place where Frankfurter came in. Frankfurter knew how to craft a law that could please Old Isaiah. Through the summer months, Frankfurter would see the president nearly daily, recording in a letter to Marion: “FD wants me really around—so that I’ve not dined out of the White House once.” The new White House policy became that the president must not repeat his angry press conference about the Supreme Court, or even mention it. Rage must wait.

Tommy Corcoran and Ben Cohen were also helping. The president had David Lilienthal at the TVA, another Frankfurter “hot dog.” With the legal talent Roosevelt was now marshalling, the shift he sought became feasible.

To be sure, there were economic justifications for the new policy. Helping the worker with his pension made his family happier and more productive. Bringing down big enterprises and wealthy families liberated smaller companies and strivers to thrive—this was Brandeis’s thesis. Giving cash to new constituents meant that they would spend and strengthen the economy—that was what Marriner Eccles, now governor at the Federal Reserve Board, was still telling the president. Taxing big business might also balance the budget, just as Roosevelt had learned as a young man. The president relished squeezing cash for the poor out of the well-to-do, especially after Tommy Corcoran and Ben Cohen or Robert Jackson had worked him up, regaling him with tales of wrongdoing by the rich.

But the emphasis remained political. “He illuminated objectives—even fantastically unrealizable objectives. These excited and inspired,” Ray Moley would later write of Roosevelt, only slightly bitterly. “When one set of these objectives—FDR loved the word—faded, he provided another.” The fact that he shifted did not have to matter.

Frankfurter, now closer to Roosevelt than ever, noted all this, and also understood that the president was making history, turning away not only from utopians but also from the moderates in his own party. “Last night,” he wrote in a memorandum that summer, “after a very delightful dinner on the South Porch, the President asked Ferdinand Pecora and me into his study in the Oval Room.” Thinking aloud, Roosevelt told his guests about Democrats in Congress, “at bottom, the leaders like Joe Robinson, though he has been loyal, and Pat Harrison are troubled about the whole New Deal. They just wonder where the man in the White House is taking the old Democratic Party.” The Democratic lawmakers feared, Roosevelt concluded, “that it is going to be a new Democratic Party which they will not like.” Still, Roosevelt was resolute: “I know the problem inside my party but I intend to appeal from it to the American people and to go steadily forward with all that I have.” As Roosevelt in 1936 would freely acknowledge to another adviser, the election was about a single issue—Roosevelt. The country had come so far from Coolidge, who had sought to remove the “me” from every scenario he evaluated.

In advancing this plan, Roosevelt was also refining his definition of his forgotten man. Before, the forgotten man had been something of a general personality—albeit always a poor one. In projects like the NRA, and with grand planners like Arthur Morgan, there had at least been the attitude that the country was all in it together. Now, by defining his forgotten man as the specific groups he would help, the president was in effect forgetting the rest—creating a new forgotten man. The country was splitting into those who were Roosevelt favorites and everyone else. The division started at the top. The president pulled increasingly close to legal pragmatists and yes men—Frankfurter and his entourage, Lilienthal at the TVA, Henry Morgenthau, even Henry Wallace at Agriculture. (Moley, increasingly on the outs, had especially little regard for Wallace: “His oratorical support of his boss” in campaigns, Moley would write later, “was as intolerably partisan as a paid party

Spieler,

and though he could find no wrong with his own party, he routinely compared the opposition

to ‘Nazis and blackguards.’”) He was also pushing away those old allies whose views were too idealistic or simply inconvenient—Tugwell, Moley, Arthur Morgan. Jim Farley, his postmaster and national chairman of the Democratic Party, would encourage this change. It was not good to look too radical. To Tugwell, it was bitter: “I had worked hard and felt I was entitled to speak.” Yet he found that “Roosevelt agreed with Farley to keep me quiet and hidden.”

Lower down, the constituencies were also of the president’s choosing. Roosevelt rejected, for example, the Bonus Army marchers who had helped him win his first election, refusing to sign a bonus into law. To his mind his plan for Social Security would take care of the marchers; they could receive theirs with all the rest. Congress in any case would do his work for him, restoring programs that had been in place before he cut them back in 1933. He also created new constituent groups. Roosevelt disliked handing out money to the poor. He wanted, as he said, to “quit this business of relief.” Instead he would create work now in other ways. That summer—the summer of 1935—Hopkins was spending the first dollars in the Works Progress Administration, a program that would, the papers said, start 100,000 projects and hire by the millions over the coming months. General Johnson would be the administrator, a job to replace his old post at the NRA. Here, Hopkins and Ickes, always competitive, were going head-to-head in an alphabet competition: Ickes had his PWA, and now Hopkins had the WPA. The WPA work was project-oriented: WPA staffers ran hospitals and dug ditches, opened libraries and served a million school lunches a day. But there was also a financial distinction: Ickes’ projects generally were the ones that cost over $25,000; Hopkins’s ran under the $25,000 line.

Hopkins established the Federal Writers’ Project to employ unemployed writers, and gave them the legitimately useful task of writing travel guides to towns and regions across the country. Among the hires were 150 jobless newspapermen, whose new jobs had a circular aspect: they were to chronicle the advances of the WPA. Hopkins picked Hallie Flanagan of Vassar to create a theater that would

air plays about the social conditions in the country—and again, spotlight New Deal progress.

This was a chance to hire new tiers of intellectuals. The Federal Writers’ project engaged not only John Cheever and Ralph Ellison but also Anzia Yezierska, John Dewey’s old friend. A young black writer named Richard Wright repeated a few lines of a song he had heard: “Roosevelt! You’re my man! / When the times come / I ain’t got a cent / You buy my groceries / And pay my rent!”

A National Youth Administration would provide work and education for thousands of college-age young people and high schoolers. The NYA had its own vast bureaucracy; one worker would be a young Texan, Lyndon Johnson. Consumers were Roosevelt’s people too, for the fact that consumers were voters was Roosevelt’s central epiphany. It was what made the spending that Eccles advised so very useful.

Then there were the blacks. The Roosevelt camp conducted an intensive outreach to all black groups. William Andrews, one of two African Americans in the New York State Assembly, likened FDR to Lincoln before his colleagues in the assembly; Irwin Steingut, also a Democrat although not black, added that the comparison was apt because Roosevelt was “a great emancipator of his time.” Harold Ickes would spend the year serving as Roosevelt’s emissary to this group. And many responded—black registration to vote rose. Ickes’s projects gave blacks a greater share of construction work than they had ever been allotted; a million blacks would take literary classes funded in some way by Washington that decade.

But there was also new hostility to the enemies Roosevelt had chosen: big companies, employers, the wealthy, those shadows that Moley had described as inhabiting the background of Frankfurter’s life. Utilities were clearly the enemy now as well. The skirmishes were over; the class war was out in the open.

His plan in place, Roosevelt opened fire. He hadn’t highlighted taxes in a while; they were seen now as merely a part of the greater 1930s story. Visiting her old school, Todhunter, in May, Eleanor had inspected state and federal tax returns prepared by the girls as a study project. Now, however, FDR too turned to taxes. In a message

sent to be read aloud to Congress, he railed against the “great accumulation of wealth” and called for a tax bill to change society. The Mellon prosecutions of the spring came to mind. The president wanted rich families to pay an estate tax when they died, but he also wanted their children to pay a second levy, a new inheritance tax, when they inherited the money. There would be a graduated corporate income tax, a shift from the old flat rate for companies, in accordance with Brandeis’s philosophy that big was bad. There would be a sharp increase at the top of the rate schedule for earners above $50,000. And there would be a tax on intercorporate dividends. Roosevelt relished the suddenness of his surprise. Speaking of the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, he told Ray Moley, “Pat Harrison’s going to be so surprised he’s going to have kittens on the spot.” Moley disapproved again. The “proposals ran counter to the New Deal’s most elementary objectives,” he said; limiting corporate surpluses would prevent companies, especially small ones, from using their cash to keep workers in downturns, and deepen depressions by leaving companies nothing with which to pay dividends in hard times. “It will aggravate fear,” summed up the

Boston Herald.

Roosevelt was unfazed. Indeed, rather than invite a full-fledged review, he boldly proposed the change as a rider to other legislation. Some members of Congress—those to Roosevelt’s left, pushing for even more punishment for the rich—needed little convincing. Hearing the clerk read Roosevelt’s words, Huey Long cried out from the floor, “Mr. President, before the President’s message is referred to the Committee on Finance, I wish to make one comment. I just wish to say ‘Amen.’” But others were disturbed that the president would try to slip such major legislation in as a rider before the July 4 break. The president shortly canceled the rush order but persisted with the plan.

Among the first to pick up on what Roosevelt was doing was Lilienthal. Arthur Morgan still backed the idea of sharing a grid with the power companies; striking such a deal, after all, would give him the time and space to build up his utopia. Lilienthal always said he

was above politics—“a river has no politics,” as he had said. Still, this was disingenuous, for his actions were all about gaining power. Now Roosevelt had given him new ammunition. Lilienthal therefore busied himself trying to write contracts with municipalities to squeeze Willkie out of the towns. Where he failed—and he was still, mostly, failing—he compensated by delivering his speeches. Earlier in the year, the town of Norris had been finished; both Lilienthal and Arthur Morgan were settling in—their homes were within five minutes of each other. “Boys and Girls Have Been Making Money in Norris” would read a headline in the educational trade press. The Norris School Cooperative enabled children to pool their labor, and even sell insurance and make loans. Nancy Lilienthal, the daughter of director David Lilienthal, would be one of the child leaders in the cooperative.