Founding Myths (11 page)

Authors: Ray Raphael

A few current textbooks for lower grades don't bother with hedges or gimmicks but repeat the story point-blank, walking back nineteenth-century excesses (Molly's husband is wounded, not killed, and she receives no reward from Washington) but making no further apologies: “American women also won fame for their bravery during the war. Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley earned the name Molly Pitcher by carrying fresh water to American troops during the Battle of Monmouth in New Jersey in 1778. When her husband was wounded, she took his place in battle, loading cannons.” This text wraps around an image of “Mary McCauley” in a full dress, ramming a rod into a cannon's barrel.

52

One current high-school text, published in 2012, unabashedly tells the same story, but with this long-discredited addition: “Afterward, General Washington made her a noncommissioned officer for her brave deeds.”

53

The Internet, meanwhile, has helped Molly Pitcher withstand attacks based on the historical record. Like nineteenth-century paintings, it is a medium that rewards excess. As of this writing, a Google search on the Internet reveals 485,000 hits for “Molly Pitcher”âand this number is increasing rapidly. Students hoping to produce reports on Revolutionary heroines can find a wealth of information on the Net, including digitized reproductions of those flamboyant Molly Pitcher paintings. Many of these enterprising young scholars, following a folkloric tradition appropriate for our times, post their own minibiographies of Molly Pitcher on the Web.

Meanwhile, Amazon lists more than a dozen commercial biographies intended for children, two of which are cited as sources for the Molly Pitcher entry in Wikipedia. “During training, artillery and

infantry soldiers would shout âMolly! Pitcher!' whenever they needed Mary to bring water,” the Wiki article says, and the claim is duly referenced to a book titled

Molly Pitcher: Heroine of the War for Independence

, for ages nine and up. Wikipedia continues: “After the battle, General Washington asked about the woman whom he had seen loading a cannon on the battlefield. In commemoration of her courage, he issued Mary Hays a warrant as a noncommissioned officer. Afterward, she was known as âSergeant Molly,' a nickname that she used for the rest of her life.” The reference is to

They Called Her Molly Pitcher

, age range three to seven.

54

Also for the younger set, Molly Pitcher has her own trading card in the Topps American Heritage Heroes series. The text:

MOLLY PITCHER

AMERICAN REVOLUTION

NON

-

COMMISSIONED SERGEANT

The image: Molly jamming her rod into the cannon's barrel, gazing intensely at her target, with an officer on horseback in the background (could it be General Washington?) looking on approvingly.

THE RETURN OF CAPTAIN MOLLY

Even if the legend is flawed, Molly Pitcher does introduce women camp followers into the core narrative of the Revolutionary Warâbut these women enter the story under false pretexts. In truth, they were more like the historic Captain Molly from the Hudson Highlands than the fanciful Molly Pitcher. They were poor and “vulgar,” in the parlance of the times. Like Mary Hays, Margaret Corbin, and the soldiers themselves, many drank and swore. (“Molly was a rough, common woman who swore like a trouper,” an elderly woman from Carlisle recalled of Mary Hays McCauley decades later. “She smoked and chewed tobacco, and had no education whatsoever. She was hired

to do the most menial work, such as scrubbing, etc.”)

55

These women were part of camp life, not above it.

Unlike the fabled Molly Pitcher, camp followers were not honored by Washington for their deeds. Quite the reverse. Starting on July 4, 1777âon the first anniversary of the Declaration of IndependenceâWashington issued orders for the women who accompanied the Continental Army not to ride on the wagons. Again and again he repeated these orders: women should walk, not ride, and they should stay in the rear with the baggage. For a general trying to put together a respectable army, camp followers were to be tolerated at bestâand the fewer the better, as far as the commander in chief was concerned. “The multitude of women,” he wrote in 1777, “are a clog on every movement. . . . Officers commanding brigades and corps [should] use every reasonable method in their power to get rid of all such as are not absolutely necessary.”

56

Common soldiers, on the other hand, appreciated the women among them. Contrary to general orders, they let women ride in the wagons clear to the end of the war. The only “reward” bestowed on female camp followers was the respect of their male peers. After the war, these men kept the memory of “Captain Molly” alive. When telling old stories, they recalled their own “Captain Mollies,” those courageous camp followers who braved the heat of the action at Fort Washington, Fort Clinton, Brandywine, Monmouth, and other historic battlefields. Decades later, when these stories congealed into one and were set in print, veterans who were still alive came forth proudly: “Yes, that must have been her. I saw that woman. I knew the heroine myself.”

While Captain Molly has a legitimate place in the story of our nation's birth, Molly Pitcher does not. The story of Molly Pitcher belongs to the nineteenth century, and it is historically significant as folklore. This appealing heroine serves men, fights tough, and is rewarded by men in high placesâbut she does not represent the female presence in the Revolutionary War, as some writers now contend; she

distorts it. To tell history as it truly was, our heroine would be “Molly of the Buckets, Pails, and Heavy Burdens”; she would not wait till her husband died or was wounded to help with the cannons; and she would receive little if any recompense, certainly no gold or officer's commission from General Washington.

Â

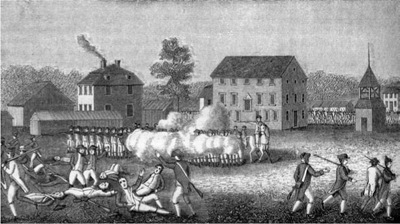

“British professionals . . . pump[ed] shot into the backs of fleeing Minute Men.”

The Battle of Lexington.

Reduced engraving by Amos Doolittle, 1832, from his original engraving, 1775, based on a sketch by Ralph Earl.

“THE SHOT HEARD 'ROUND THE WORLD”

E

very year, over one million Americans commemorate “the shot heard 'round the world” with a patriotic pilgrimage to Minute Man National Historical Park on the outskirts of Concord, Massachusetts. On April 19, the anniversary of the famous event, reenactors dress up as colonial minute men and march from nearby towns to Lexington and Concord, where they exchange make-believe musket fire with friends and neighbors dressed as British Redcoats. Throughout the state, and in Maine and Wisconsin as well, “Patriots' Day” is celebrated as an official holiday.

The story is classic David and Goliath, starring rustic colonials who faced the world's strongest army. At dawn in Lexington on April 19, 1775, several hundred British Regulars, in full battle formation, opened fire on local militiamen. When the smoke had cleared, eight of the sleepy-eyed farmers who had been rousted in the middle of the night lay dead on the town green.

In the wake of the bloodbath, to mobilize popular support, patriots proclaimed far and wide that the Redcoats had fired first. The Massachusetts Provincial Congress collected depositions from participants and firsthand witnesses, then published those accounts that conformed

to the official story under the title

A Narrative of the Excursion and Ravages of the King's Troops.

British authorities countered with their own official version: the Americans had fired first. Not surprisingly, this story received little circulation in the rebellious colonies.

Because of the biases and agendas of the witnesses, we can never know for sure who fired the first shot at Lexington. But we do know that the patriots won the war of words. “The myth of injured innocence,” as David Hackett Fischer calls it, became an instant American classic.

1

We have all learned that the British started the American Revolution when they opened fire on outnumbered and outclassed patriot militiamen on the Lexington Green. But this makes no sense. Revolutions, by nature, are proactiveâthey must be initiated by the revolutionaries themselves. The American Revolution had begun long before the battle at Lexington.

In 1836 the poet and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson coined a catchy phrase that has signified the event ever since: “the shot heard 'round the world.” Actually, Emerson's poem “Concord Hymn” commemorated the fighting at the North Bridge in nearby Concord, and his celebrated “shot” was fired by Americans:

Â

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Â

Their flag to April's breeze unfurled,

Â

Here once the embattled farmers stood,

Â

And fired the shot heard 'round the world.

Over time, however, Emerson's poem was relocated to Lexington, a site more hospitable to the story we wish to hear. At Lexington the farmers were clearly the victims, while at Concord they were not. The David and Goliath tale, highlighted by the image of bullying British troops mowing down Yankee farmers, has prevailed. Popular histories still repeat the story as it was first told by American patriots, making it very clear who fired the first shot: “British professionals . . . pump[ed] shot into the backs of fleeing Minute Men.”

2

Current textbooks routinely locate “the shot heard 'round the world” to the

standoff at Lexington, not the “rude bridge” at Concord, where Emerson placed it. One grade-school text, even as it quotes the “Concord Hymn” verbatim in a sidebar, says Emerson called the first shot fired at Lexington “the shot heard 'round the world.”

3

A college text, after outlining the events at both Lexington and Concord, tries to have it both ways by misquoting Emerson, switching from the singular to the plural: “The first

shots

ââthe

shots

heard 'round the world,' as Americans later called themâhad been fired. But who had fired them first?” It then discusses the debate over who had fired the first shot at Lexington, showing a clear preference for that location.

4

But what if the roles were reversed? What if American Revolutionaries were actually Goliath, and the British occupying force, greatly outnumbered and far from home, more like David? In fact, the American Revolution did not begin with “the shot heard 'round the world,” wherever it was fired. It started more than half a year earlier, when tens of thousands of angry patriot militiamen ganged up on a few unarmed officials and overthrew British authority throughout all of Massachusetts outside of Boston. This powerful revolutionary saga, which features Americans as Goliath instead of David, has been bypassed by the standard telling of history. By treating American patriots as innocent victims, we have suppressed their revolutionary might.

BELEAGUERED BOSTON

At Lexington, the story goes, poorly trained militiamen, aroused from their slumber by Paul Revere, were surprised and mowed down by British Regulars. Surprised? Untrained? Unprepared? Let's take a closer look at events that culminated in “the shot heard 'round the world.”

On December 16, 1773, patriots dressed as Indians dumped 342 chests of tea into Boston Harbor. On the night of April 18, 1775, sixteen months and two days later, British troops marched from Boston toward Lexington and Concord. Blood was shed, lots of it, and a

war was on. What, exactly, happened during that intervening sixteen months and two days? How did an act of political vandalism lead to outright warfare?

Here is one response, repeated for generations in our textbooks and in almost all accounts of the American Revolution.

To punish Boston for what we now call the Boston Tea Party,

5

Parliament passed four bills it called the “Coercive Acts” and colonists dubbed the “Intolerable Acts.” The “most drastic” of these was the Boston Port Act, which closed the port of Boston.

6

(The others are generally listed but rarely discussed in any detail.) This measure was supposed to isolate Bostonians from other colonists, but it had the reverse effect: “Americans in all the colonies reacted by trying to help the people of Boston. Food and other supplies poured into Boston from throughout the colonies.”

7

Meanwhile, leaders in twelve colonies gathered in the First Continental Congress to show support for Boston and present a united opposition to Britain's harsh move. Congress petitioned Parliament to change its course, but Parliament remained firm. Six months later, British Regulars marched on Lexington and Concord.