Founding Myths (2 page)

Authors: Ray Raphael

Selective written sources, rich but loose oral and visual traditions, and the intrusion of politics and ideologyâthese have presented open invitations to the historical imagination. Creatively, if not accurately, we have fashioned a past we would like to have had.

Fiction parted from fact at the very beginning. Shortly after the Revolutionary War, Charles Thomson, secretary of the Continental Congress, embarked on writing a history of the conflict. Privy to insider information, Thomson had much to revealâbut then, surprisingly, he gave the history up. “I shall not undeceive future generations,” he later explained. “I could not tell the truth without giving great offense. Let the world admire our patriots and heroes.”

3

Since people like Mr. Thomson chose not to tell the truth, what might they tell instead? In 1790 Noah Webster provided an answer: “Every child in America,” said the dean of the Anglo-American language, “as soon as he opens his lips . . . should rehearse the history of his country; he should lisp the praise of Liberty and of those illustrious heroes and statesmen who have wrought a revolution in his favor.”

4

So the romance began. Starting in the decades following the Revolution and continuing through much of the nineteenth century, writers and orators transformed a bloody and protracted war into glamorous tales conjured from mere shreds of evidence. We still tell these classics todayâPaul Revere's ride, “Give me liberty or give me death,” the shot heard 'round the worldâand we assume they are true representations of actual occurrences. Mere frequency of repetition appears to confirm their authenticity.

Our confidence is misplaced. In fact, most of the stories were created up to one hundred years after the events they supposedly depict. Paul Revere was known only in local circles until 1861, when Henry Wadsworth Longfellow made him immortal by distorting every detail of his now-famous ride. Patrick Henry's “liberty or death” speech first appeared in print, under mysterious circumstances, in 1817, forty-two years after he supposedly uttered those words. The “shot heard 'round the world” did not become known by that name until 1836, sixty-one years after it was fired.

The list goes on. Samuel Adams, our most beloved rabble-rouser, lay low through the first half of the nineteenth century, only to be revived as the mastermind of the Revolution three-quarters of a century after the fact. Thomas Jefferson was not widely seen as the architect of American “equality” until Abraham Lincoln assigned him that role, four score and seven years later. The winter at Valley Forge remained uncelebrated for thirty years. Molly Pitcher, the Revolutionary heroine whose picture adorns many elementary and middle-school textbooks today, is a complete fabrication. Her legend

did not settle firmly on a specific, historic individual until the nation's centennial celebration in 1876.

These stories, invented long ago, persist in our textbooks and popular histories despite advances in recent scholarship that disprove their authenticity. One popular schoolbook includes all but two of the tales exposed in this book, and several of the stories, still taken as gospel, are featured in all modern texts.

5

Why do we cling to these yarns? There are three reasons, thoroughly intertwined: they give us a collective identity, they make good stories, and we think they are patriotic.

We like to hear stories of our nation's beginnings because they help define us as a people. Americans have always used the word “we,” highlighting a shared sense of the past. Likewise, this book uses the first person plural when referring to commonly held beliefs. This usage is more than just a linguistic convenienceâit pinpoints actual cognitive habits.

We

are history's protagonists. Few Americans read about the Revolutionary War or World War II without identifying with

our

side. George Washington, we are told in myriad ways, is the father of

our

country, whether our forebears came from England, Poland, or Vietnam.

6

Like rumors, the tales are too good

not

to be told. They are carefully crafted to fit a time-tested mold. Successful stories feature heroes or heroines, clear plotlines, and happy endings. Good does battle against evil, David beats Goliath, and wise men prevail over fools. Stories of our nation's founding mesh well with these narrative forms. American revolutionaries, they say, were better and wiser than decadent Europeans. Outnumbered colonists overcame a Goliath, the mightiest empire on earth. Good prevailed over evil, and the war ended happily with the birth of the United States. Even if they don't tell true history, these imaginings work as stories. Much of what we think of as “history” is driven not by facts but by these narrative preferences.

This imagined past, anointed as “patriotic,” paints a flattering self-portrait of our nation. We pose before the mirror in our finest

attire. By gazing upon the Revolution's gallant heroes, we celebrate what we think it means to be an American. We make our country perfectâif not now, at least in the mythic pastâand through the comforting thought of an ideal America, we fix our bearings. We feel more secure in our confused and changing world if we can draw upon an honored tradition.

But is this really “patriotism”? Only from a narrow and outdated perspective can we see it that way. Our nation was a collaborative creation, the work of hundreds of thousands of dedicated patriotsâyet we exclude most of these people from history by repeating the traditional tales. Worse yet, we distort the very nature of their monumental project. The United States was founded not by isolated acts of individual heroism but by the concerted revolutionary activities of people who had learned the power of working together. This rich and very democratic heritage remains untapped precisely because its story is too big, not too small. It transcends the artificial constraints of traditional storytelling. Its protagonists are too many, and too real, to be contained within simple morality tales. This sprawling saga needs to be toldâbut our founding myths, neat and tidy, have concealed it from view.

7

Traditional stories of national creation reflect the romantic individualism of the nineteenth century, and they sell our country short. They are strangely out of sync with both the communitarian ideals of Revolutionary America and the democratic values of today. “Government has now devolved upon the people,” wrote one disgruntled Tory in 1774, even before war broke out, “and they seem to be for using it.” Yes, indeed. That's a story we do not have to conjure, and what an epic it is.

8

Â

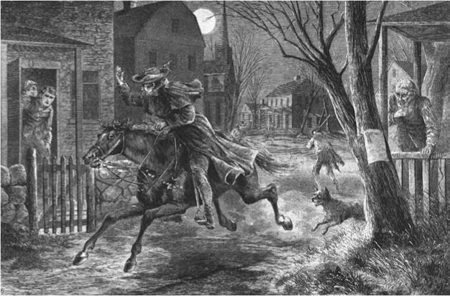

“The fate of a nation was riding that night.”

Paul Revere's Ride.

Drawing by Charles G. Bush,

Harper's Weekly,

June 29, 1867.

O

n April 5, 1860, while walking past Boston's Old North Church, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow heard a folkloric rendition of Paul Revere's midnight ride from a friend, George Sumner. The story stirred him, and the next day he began setting thoughts to paper.

1

With the United States on the verge of splitting apart, Longfellow, a unionist, was inspired by the dramatic opening to the American Revolution, when “the fate of the nation” (as he would soon write) seemed to hinge on a single courageous act. For the noted poet, Revere was a timely hero: a lonely rider who issued a wake-up call. If Revere had roused the nation once, perhaps he could do it again, this time riding the rhythmic beat of Longfellow's verse:

Â

So through the night rode Paul Revere;

Â

And so through the night went his cry of alarm

Â

To every Middlesex village and farm,

Â

A cry of defiance, and not of fear,

Â

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

Â

And a word that shall echo forevermore!

Â

For, borne on the night-wind of the Past,

Â

Through all our history, to the last,

Â

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

Â

The people will waken and listen to hear

Â

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

Â

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.

2

In close replication of Revere's own effort, Longfellow passed word of the ride to every household on America's highways and byways, issuing his alarm, line by line, as he distorted every detail of the actual deed. In the process, he transformed a local favorite into a national legend.

Longfellow himself made history in two ways: he conjured events that never happened, and he established a new patriotic ritual. For a century to follow, nearly every schoolchild in the United States would hear or recite “Paul Revere's Ride.” In their history texts, students read pared-down prose renditions of Longfellow's tale, the meter gone but distortions still intact. Even today, one line remains in our popular lexicon, known to those who have never read or heard the entire piece: “One, if by land, and two, if by sea.” These words, all by themselves, call forth the entire story, and Paul Revere's ride remains the best-known heroic exploit of the American Revolution.

THE EARLY YEARS

Before Longfellow, Paul Revere was not regarded as a central player in the Revolutionary saga. He was known for his engravings (especially his depiction of the Boston Massacre), for his work as a silversmith, and for his political organizing in prewar Boston. John Singleton Copley painted his portrait, which showed Revere displaying his silver workâbut that was several years

before

the midnight ride.

3

Locally, Revere was also remembered as a patriotic man who climbed on a horse and rode off with a warningâbut similar feats had been performed by countless others during the Revolutionary War. Although Revere was certainly respected for the various roles he

played, he wasn't exactly celebrated. Schoolbooks made no mention of Revere or his derring-do.

Shortly after the fact, Paul Revere offered his own rendition of the ride that would someday make him famous. Three days after British Regulars marched on Lexington and Concord, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress authorized the collection of firsthand reports from those who were participants or observers. Paul Revere came forward to tell what he knew.

4

Revere's versionâin simple prose, not verseâdiffered considerably from Longfellow's. At about 10 o'clock on the evening of April 18, 1775, Revere stated in his deposition, Dr. Joseph Warren requested that he ride to Lexington with a message for Samuel Adams and John Hancock: “a number of Soldiers” appeared to be headed their way. Revere set out immediately. He was “put across” the Charles River to Charlestown, where he “got a Horse.” After being warned that nine British officers had been spotted along the road, he set off toward Lexington. Before he even left Charlestown, he caught sight of two, whom he was able to avoid. “I proceeded to Lexington, thro Mistick,” Revere stated flatly, “and alarmed Mr. Adams and Col. Hancock.”

That was itâRevere devoted only one short sentence to his now-mythic ride. Additions were to come later. Nowhere in his statement did Revere mention the lantern signals from the Old North Church, a matter that seemed more trivial to him than it did to Longfellow. On the other hand, Revere did include much concrete information that Longfellow would later suppress, such as the fact that Dr. Warren sent a second messenger, a “Mr. Daws” (William Dawes), along an alternate route.

For Revere, the night featured a harrowing experience that Longfellow, for reasons of his own, saw fit to overlook. After giving his message to Adams and Hancock, Revere and two others set out toward Concord to warn the people thereâbut he did not get very far before being captured by British officers. For most of the deposition, Revere talked of this capture, of how the officers had threatened to

kill him five times, three times promising to “blow your brains out.” Though he had carried messages from town to town many times before, Revere had never encountered such serious danger. In his mind, this was the main event of the story.

5