Framingham Legends & Lore (17 page)

Read Framingham Legends & Lore Online

Authors: James L. Parr

Macomber was the president of the Massachusetts Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (MSPCA) for forty years, and along with his prized horses he kept show dogs, a donkey and even a monkey at the estate. After the horse racing ended, he continued to hold large events at the estate including Kennel Club shows, antique automobile rallies and the Millwood Hunt Club's Annual Horse Show. In June 1950, Macomber hosted a celebration of the town's 250

th

anniversary at Raceland. Twenty-five thousand guests attended a concert given by the Boston Pops under the direction of Arthur Fiedler. Upon Macomber's death in 1955, the bulk of the property was left to the MSPCA, which operated an animal life center there from 1971 to 1984.

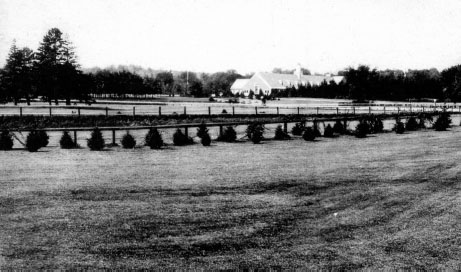

The track at Raceland, the estate of John Macomber.

John Bowditch was the son of E.F. Bowditch, who had begun the Millwood Hunt Club on his 660 acres in north Framingham in 1866. The elder Bowditch introduced English-style fox hunting to Framingham, with imported foxhounds tracking actual foxes across his vast property. The fox hunt continued off and on until about 1912. In 1922, John Bowditch revived the traditional fox hunt, but quickly switched over to the more humane drag hunt, in which hounds followed a scent laid down over the trails by a volunteer. For many years the club sponsored a horse show, and in 1966 it celebrated its 100

th

anniversary. But within three years the club had disbanded, a casualty of increased residential development in the northern part of town.

Although the equine and agricultural spectacles that entertained generations of Framinghamites ended years ago, many of the venues at which they took place have been preserved as parkland or protected conservation areas. The Middlesex South Fairgrounds were transformed into the town's Bowditch Field, complete with running track, football field and bleachers built by the Works Progress Administration during the Depression in the 1930s. A portion of the Macomber property along Salem End Road was developed into housing after the MSPCA closed down its operations in 1984, but the town acquired a parcel of 57 wooded acres that today is open to the public as the Macomber Conservation Land and Trails. The fields and forests that once echoed with the braying of hounds hot on the scent in the days of the Millwood Hunt are now host to leashed pooches and their owners strolling the paths of the 820-acre Callahan State Park.

T

HE

M

ARATHON

C

OMES TO

T

OWN

Since its inaugural run in 1897, the Boston Marathon has had several route changes over the twenty-six-mile course, but the path to victory has always taken runners down Route 135 through the heart of Framingham. The two-and-a-half-mile section of the course that runs through town is relatively flat and only three miles from the starting line, so it lacks the drama of Heartbreak Hill in Newton or the excitement of the finish line in Copley Square. But that does not stop the thousands of spectators who line Waverly Street every Patriots' Day from enjoying the race. In 1907, one such crowd got more excitement than it anticipated when bystanders witnessed an event that affected the outcome of the race and has since become a part of Marathon lore.

Marathon fans had been talking for weeks about the upcoming race, with special interest paid to Tom Longboat, a nineteen-year-old Canadian phenomenon. Longboat, a full-blooded Onondaga from Ontario, was picked by many to win the eleventh running of the prestigious event. Framingham fans looking for a thrilling race were not disappointed on that cold, snowy day when the first pack of about ten runners made its way down Route 135, with Tom Longboat sharing the lead. As the group approached the Waverly Street railroad crossing, a most unexpected and potentially dangerous thing happenedâa freight train slowly rumbled down the tracks approaching the intersection. The lead group saw the train and put on a burst of speed, crossing the tracks just moments before the train passed by. The next pack of runners was not so lucky. They had to run in place for nearly a minute while the train lumbered across the road. When the route was finally clear, it was too late. None of the runners in the second group was able to make up the time and distance, and young Tom Longboat won in record time, becoming a Canadian national hero. Local runner Hank Fowler of Cambridge, who was one of the runners held up by the train, hinted that he may have done better than his second place finish had the train not interfered.

C

ABBAGE

N

IGHT

Long before trick-or-treating caught on as a Halloween tradition, the evening of October 31 was chiefly celebrated with pranks, mischief and fortunetelling. A

Boston Globe

article from 1907 describes large groups of rowdy teenage girls “throwing stones and tin cans against houses,” “screeching and yelling and disturbing sick people” and responding to requests to calm down with “hooting and blasphemy.” Years later, in the 1930s, harmless Halloween pranks had escalated to the point of outright vandalism not only in Framingham, but across the nation as well. Locally, hundreds of young vandals terrorized the streets, letting air out of tires, breaking streetlights, stealing street signs and ringing doorbells. The town responded in 1936 by holding a large Halloween party on the old fairgrounds. Hundreds of costumed children enjoyed a parade, contests and games, and for the first time in several years, police reports of vandalism decreased. The party was so successful it was moved to Nevins Hall in the Memorial Building and was an annual event for many years.

Determined pranksters would not be stopped, however; they simply shifted their shenanigans to the night before Halloween, when police patrols were less frequent. The October 30 night of mayhem was called Cabbage Night in Framingham, and was similar to celebrations held in other parts of the country under names such as Mischief Night, Gate Night and Devil's Night. Cabbage Night has its origins in an old Scottish tradition. All Hallow's Eve had long been a night on which young ladies tried any number of fortunetelling techniques in order to learn more about their future spouses. Walking down the stairs backward while looking in a mirror, floating walnut shells in water and bobbing for apples were all surefire ways to get a glimpse into one's romantic future. The close examination of a cabbage pulled right out of a neighbor's patch could foretell the attributes of a potential husband. Once the cabbage had served its purpose, the only logical thing to do with it was to throw it against the neighbor's door and run really fast, thus beginning a long tradition of Halloween pranks. Framingham teens observing Cabbage Night skipped the fortunetelling and stuck with the vegetable throwing, adding it to their already large repertoire of tricks. While other communities in the area observe the night before Halloween in similar fashion, Framingham is one of the few towns to attach the vegetable-themed moniker to the celebration. Perhaps the name choice was an unintended tribute to the town's rich agricultural past.

Chapter Seven

FRAMINGHAM IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

D

ENNISON

M

ANUFACTURING

AND

R.H. L

ONG

As the twentieth century dawned, South Framingham continued to prosper. It was where the newspapers were located, where most retail establishments opened their doors and where you could catch the train to Boston. There was a veritable building boom as large office blocks, schools, churches, the armory and banks were all built downtown.

Most of all, it was where the manufacturing jobs were. The Dennison Manufacturing Company took over the moribund works of the Para-Rubber Company in 1897, located right along the rail lines. The maker of boxes, labels, tags, crepe paper and the like soon became the town's largest employer and remained so until late in the twentieth century. As a result, Framingham earned the nickname “Tag Town.” The Dennison family moved to town and soon demonstrated that their public-minded ideals matched those of the Simpson family when they had ruled Saxonville. Dennison was run on progressive ideals as to workers' rights, employee ownership and quality of work life. Henry Dennison became a national figure, especially during the New Deal years, with his innovative ideas as to how worker and capital could cooperate and profit together. In 1945, a delegation even proposed that Dennison's estate off Edmands Road in north Framingham would be an ideal site for the headquarters of the newly formed United Nations, given Framingham's excellent transportation facilities and relative proximity to both Boston and New York. It took only a moment for Dennison to picture what this would mean for his peaceful estate and convince the delegation never to raise the question again.

Another large manufacturer was the R.H. Long Shoe Company. Richard Long prospered in the shoe trade, but he had other interests as well. He ran for governor of Massachusetts as a Democrat, only to lose soundly to future president Calvin Coolidge. (He did not even carry his hometown of Framingham, although he came closer than any other Democrat did in that era.) In the 1920s, he decided to jump into the automobile business back when any number of amateur mechanics started building their own cars in garages with hopes of making it big. Long's Bay State automobile was undoubtedly a handsome vehicle, and several thousand were made before he pulled the plug on the operation in 1926.

T

HE

N

EW

I

MMIGRANTS

The following article regarding a crew working on the abutment of a bridge over the railroad tracks at Park's Corner in South Framingham appeared in the

Framingham Tribune

, May 16, 1891:

The Italian quarters at Park's cornerâ¦burned at noon Fridayâ¦There was a barn worth about $300 and a cottage house worth about $400. Both were occupied by the Italians, nearly fifty in number, and stood very near the

[Boston & Albany]

railroad tracks, and it was supposed that the stable, covered with tar paper, took fire from the sparks of a locomotive. The stable was burning at or before 11 o'clock in the morning, and before some of the occupants came home to dinner at noon the house was all on fire. Both were totally destroyedâ¦

The Italians had been loafing a week on account of a misunderstanding about prices, but had been paid off, and went to work again Thursday morning, the day before the fire. They had consequently spent little of the money that they had received, and some of them claimed that they lost their money in the fire and others lost clothing. One Italian lost a watch and chain and another a new suit of clothes just bought. The Italians were thrown into utter consternation and confusion by the fire, and their excitable natures were seen in full play by the spectators. Many of them were crying at the loss of their goods. They left the place in a body, and all went into Boston on an early afternoon train, and will probably not work in Framingham again, so that others will have to be engaged to finish the job

.

The article illustrates how novel the residents of Framingham found the presence of Italian laborers in their town. We are informed that the men had been “loafing” for a week during a pay dispute. The taciturn Yankees marveled at the “excitable natures” of the workers, although given how much they lost, and given how little they probably had, their emotional response seems entirely justified under the circumstances. That the fifty men were quartered in a cottage and a barn did not seem to raise any eyebrows. The most concern expressed by the reporter was in consideration of who would now complete the construction of the bridge abutment.

If Italians were unquestionably alien to Framingham residents in 1891, objects of wonder and scorn, within twenty years they had become a part of the community. They took many of the new jobs in construction or at the Dennison, Long or other factories. They dominated the neighborhood south of Waverly Street (Route 135) and west of Winthrop, which became known as “Tripoli.” The Christopher Columbus Society was founded in 1908, St. Tarcisius Church was dedicated a year later and Columbus Hall on Fountain Street was opened in 1911. Perini Construction, founded in Ashland in 1894, relocated to Framingham in 1931 and immediately became one of the largest construction firms in the region. In the American immigrant tradition, by 1938 the Italian community had achieved sufficient sway within the town that the square in front of Columbus Hall was renamed Columbus Square. Though the Italians were the largest group, they were joined by Greeks, Eastern European Jews and many other ethnicities living side by side in South Framingham.

S

OUTH

F

RAMINGHAM

I

S

F

RAMINGHAM

N

OW

By 1910, South Framingham had been the tail wagging the dog for decades, as the more vibrant, populous part of town. No one confused “downtown” with the rustic Main Street at Framingham Centre. In 1913, the post office made this change officialâthe “South Framingham” post office became the “Framingham” post office, while the old Framingham post office was now designated “Framingham Centre.” Somehow this bureaucratic ruling put the official imprimatur on a change that had been eighty years in coming. In 1928, the construction of the Nevins building as the new town hall at the junction of Union Avenue and Concord Street further ratified the changing of the guard. (Still, the main branch of the public library did not move downtown until 1979.)