Free Yourself from Fears (18 page)

Read Free Yourself from Fears Online

Authors: Joseph O'Connor

J What is the worst that can happen if you make this change? What is the worst case? What could happen? The worst case is not inevitable.

You may decide you can live with this. It is better than where you are now. Or you make plans to deal with these unwanted consequences.

J What is the best that can happen if you do not make this change?

What is good about life now? Are there reasons to stay where you are besides the risk involved in moving?

J How comfortable are you now? What do you value about the present situation? This question will also give you clues about the habits that keep you in place.

J What is the worst that can happen if you do not make this change?

Could the situation become intolerable? How bad is it now?

This takes us to the next step—what happens once you take action?

137

FREE YOURSELF FROM FEAR

Transition

Action takes you out of this vicious circle of fear. Then you come to a very interesting time—transition. You have left the place you were, but you have not yet arrived where you want to be. It takes time to rebalance and stabilize your life.

There is a perfect metaphor for transition in the film

Indiana Jones

and the Last Crusade

. Toward the end of the film, Indiana stands high on a ledge, looking out onto a bottomless chasm. He needs to cross it to get to the Holy Grail, which has the power to heal his dying father. He looks across the chasm. It is too far to jump and there is nothing to help him cross, no ropes and no bridges. All he has are faith and trust. So, plucking up his courage, he takes action and steps into space. Then in that marvelous moment, the camera pans to a different angle and you see that he is stepping onto a stone bridge. He

does

have the support he needs. This bridge was there all the time, but it was invisible. He could not see it from the front, because it blended into the rock walls of the chasm. Without taking the step, he would never have known. He throws some pebbles on the bridge to mark it and hurries across to his next ordeal. This is exactly how transition works. There comes a time when you have to step forward, trusting that you will have the support you need.

Another metaphor for transition is the time between one step and the next. Walking is easy once you have learned; yet it involves constantly losing your balance in order to take the next step. You commit yourself in that fraction of a second as your foot moves forward. To stay balanced you have to keep moving. We usually think of balance as static, but static balance is stiff and inflexible. Dynamic balance happens through movement. Think of a tightrope walker. In order to stay balanced, she has to move forward. When she tries to stand still, she will fall. Yet sometimes in the midst of change, this is precisely what we try to do: we freeze instead of moving forward.

Transition is not comfortable. It is ambiguous. We have to keep moving forward, but not too fast. Many people react to transition by trying to get though it as quickly as possible. This does not work.

138

DEALING WITH CHANGE

Transition takes time—and trust.

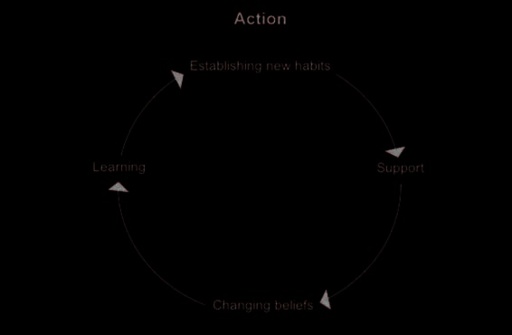

When you are in transition, you need support. You need someone who can stay with you even in this difficult time, keeping you moving forward. You need to establish new habits; you may need to change some beliefs. And you will learn something new about yourself and others.

My transition in Brazil took several months. I established a new rhythm of life in São Paulo. I enjoyed the friendliness of the Brazilian people. I watched the purple sunsets over the office blocks and ducked under the blooms of the flamboyant trees on the sidewalk. I began to learn Portuguese, a beautiful language that combines the strength of Spanish with the musical cadences of Italian.

I also saw English culture for the first time in a more objective way.

It is impossible to know your own culture while you are immersed in it; it seems

the

way to live, rather than

one

way to live. Once I began to know the Brazilian culture, then my English one became visible by contrast.

Culture is people’s collective subjective experience. In NLP, we are careful not to judge individual subjective experience. Everyone has their own map of the world, and you do not try to give them a new, 139

FREE YOURSELF FROM FEAR

“better” map, but to give them more choices on the map they already have. We need to apply the same to culture. Every culture has evolved ways of dealing with the big questions of life—how to live and survive and how to deal with and understand others. For me it is fasci-nating to embrace another culture and find other ways of answering these questions. Then, paradoxically, I could appreciate English culture better. Many things that I took for granted in England no longer apply. In Brazil, I can experience the city, the country, and the culture, what people care about and what they don’t care about. All around I can feel an intangible sense of style that comes with being Brazilian.

I enjoy living in Brazil. I swim in the warm sea on some of the most glorious beaches on the planet and enjoy the sun. I can make (and drink) Caipirinhas—a blend of ice, lemon, and Cachasa or vodka. When I look up at the night sky I see new constellations and one in particular that I had always thought romantic and exotic, the Southern Cross. The familiar constellations of the northern hemi-sphere are gone.

I have made new habits of eating, sleeping, and walking on the streets. I am used to the traffic, which snarls the city up for hours a day, and the overfriendly buses that delight in getting really close to you as they jostle their way though the narrow traffic lanes. But it took time and the transition was not always easy.

Experiencing transition

Here is an skill to explore your attitudes to change, and the fears and habits that might hold you in place. It was developed by Andrea, who also developed the transition model. It takes about 20 minutes to complete, but is worth it. At the end you will be much clearer about any change you want to make as well as what helped you make successful changes in the past. It helps to throw some pebbles on the bridge so that you can see it more easily.

140

DEALING WITH CHANGE

Skill for freedom

Transition

Part one: The challenge

Think back to a time when you made a successful change. Do not use a major change for this exercise. (My change to living in Brazil is an example of a very big change.)

The change may have been your choice, or it may have been imposed. It could be predominantly internal (where you changed your character or developed new qualities) or external (a change in external circumstances).Think about the following questions: J What was the change you went through? Describe it briefly.

J What was the trigger that led to the change?

J Were you dissatisfied with your life in some way and decided to change, or did you have a challenge from the outside that you did not choose?

J Was the change predominantly about your internal qualities, or about your outer circumstances?

J What fears did you have about the change? (Think back to all the possible bad consequences you imagined, what you were afraid of losing.)

J What habits of yours made you resist the change?

J What were the important things in your environment, for example people, places, etc. that kept those habits in place?

Part Two: Action

J What did you do to make the change? Was there a key realization that made it possible?

J What or who supported you? What resources did you need? These resources could be to do with your skills, friends, acquaintances, or your beliefs and values.

J What beliefs did you change as a result?

J What did you learn?

141

FREE YOURSELF FROM FEAR

Part Three: Change now

J Now, think of a change that you want to make in the future (internally driven change).

J What habits do you have that you will need to change? How do you feel about this?

J What fears do you have about the future?

J What do you need to believe about yourself that would make this change easier?

J How would someone act if they had that belief?

Transition takes time

Change hardly ever happens instantaneously. Transition is part of any change. You need to be ready for it.

J Don’t expect the change to happen immediately, J Expect to feel uncomfortable for a time.

J Gather your resources before you start. In particular, get support from a friend, or a professional helper if the change is a major one.

J Keep moving!

J Celebrate when you make the change successfully.

When the transition is over, you will have made the change. You will have learned something, left some things, gained others, lost some habits, and established new ones. You will have crossed the chasm.

Then, as you walk on, there will be other chasms to cross.

142

Authentic Fear—

Fear as Friend

The nine laws of safety

1 Pay attention to authentic fear.

2 The more you trust your resources the safer you feel.

3 Respect the context, time, and place.

4 To feel safe you need to feel in control.

5 To feel safe you need information that is:

—Relevant.

—Sufficient.

—Trustworthy.

6 Take sensible precautions against possible loss.

7 Have a contingency plan.

8 Pay attention to your intuitions.

9 To stay safe, pay attention to contextual and personal incongruence.

Fear as a Sign to Take Action

The fact that you fear something means that it has not happened.

AUTHENTIC FEAR IS A RESPONSE TO DANGER in the present moment. Its intention is to keep you safe. Authentic fear is evolution’s way to ensure that your body is ready to fight, or to run away. It makes you suddenly stronger, more resistant to pain, and more sensitive to what is happening—all useful responses. You cannot decide intellectually to be authentically afraid. The fear response is several steps ahead of your conscious mind; it clicks in before you have figured out what the danger is, or indeed whether there is any real danger at all.

What does authentic fear do for you? It makes you respond, it overrides whatever else you are doing and whatever goals you have, and gives you an immediate and compelling new agenda.

The first law of safety:

Pay attention to authentic fear

Authentic fear is a primary human emotion and an evolutionary mechanism for survival. We cannot live without it. A person without authentic fear would be like a person born without the ability to feel pain. This sounds appealing, but pain is a necessary signal to alert you that something is wrong. Without the ability to feel pain, you could die from appendicitis before you knew you were ill. Without pain you would not know that fire was dangerous.

Living without pain could be fatal. Living without fear would be equally dangerous.

FREE YOURSELF FROM FEARS

Authentic fear is a good ally. It stops you from becoming a victim.

People who do brave acts are not fear

less

—the very reason we admire them and see them as brave is because they feel the fear and do it anyway, unlike the usual response, which is to feel the fear and hold back. A person who was truly fearless would not be brave, but stupid.

We want to keep real fear, the fear that warns us that we are in danger. We want to keep the enjoyable fear of action adventures, or horror films, or “white-knuckle rides.”

We want to be free of the unreal fear that makes us less than we are, cripples our lives, and is not appropriate to the situation that triggered it. We need to be able to distinguish authentic fear from unreal fear. The next skill will do that.

Skill for freedom

Exploring authentic fear

Think of a time when you were afraid of something real in the present moment, where you had no choice and the fear came up suddenly.

Imagine yourself back there now. See again what you saw. Hear again what you heard and feel again what you felt.

What do you feel?

Where do you have the feeling? In what part(s) of your body?

How large is the area where you feel the sensation?

How deep is it?

How hot or cold is it?

What color does it seem to be?

Does the feeling seem to move or is it still?

Remember these qualities of authentic fear, so that it can be a reliable warning of danger to you.

146

FEAR AS A SIGN TO TAKE ACTION

You need authentic fear

When I hear advice about eliminating fear, it reminds me of the joke about the man who was arguing with St. Peter at the gates of Heaven.

St. Peter looks through the book of the man’s life and frowns.

“Well,” says St. Peter, “I can’t see that you have done anything really bad in your lifetime, but that’s only the half of it. To get into Heaven, you have to have done some good deeds, and I can’t see very many of those here either. If you can tell me one really good deed you did in your life, you can come in.”