Freedom's Children (15 page)

Read Freedom's Children Online

Authors: Ellen S. Levine

They caught a lot of kids, but I wasn't arrested that day. I escaped. I got home out of breath, scared. My parents didn't know I was on that march. I went in and told my mama that we had to run from Bull Connor, and everybody was in jail except me. She told my daddy. He just sat there and shook his head.

I thought Bull Connor was just like his name. He was a bigot, a racist. He had so much hatred in his heart. In fact, I didn't think the man had a heart. I couldn't understand how anybody could hate that much. Just for the color of your skin. I really thought he would burn in hell. Every time I would think about Bull Connor, I always saw fire around him. “Keep the niggers down!” Even with that, for some reason we were not afraid of him. We looked at him like he was an old man who was just about over the hill. Being teenagers, you're not scared of anything.

MYRNA CARTERI can't explain why I started getting involved. It was like something drawing me from the inside. I was always the one for the underdog, and problems that affected other people, affected me.

And I had a complex. I was tall. I was five feet eight inches when I was twelve. The children would tease me. I began to withdraw, and I would lose myself in books and other things.

One day my friend Carol and I decided to go to one of the meetings. Dr. King spoke, and immediately after we had commitment period. He would tell you to come forward if you were willing to fight for what was right. But you had to take an oath. You had to agree to be nonviolent. You had to agree that if anything would happen, you would turn the other cheek. He said, “If you can't do it, don't come.”

People were springing up and going down front like mad. It was just sending chills down me. The next night we went to the meeting and I looked at Carol and she looked at me. She was waiting on me and I was waiting on her. Finally we both got up and went down. They asked us to come the next morning for instructions.

At first I thought I was going to be afraid, but somehow the fear went. The drawing power in Dr. King's voice was like that of no one else who was connected with the struggle. It wasn't that we worshiped him. We certainly did not. He wasn't like that at all. I think that's why he had that power that could make you actually leap and you didn't realize you were leaping.

The very first time I was arrested, we were leaving Sixteenth Street Church trying to make it downtown. They separated us into groups. At first we didn't know why. Reverend Young lined one group up and gave them all signs and a route to go. You could hear the police motorcycles and the paddy wagons out there waiting on us.

This first group came out of the church quietly chanting, “O freedom, O freedom, O freedom over me, and before I be a slave I'll be buried in my grave, and go home to my Lord and be free.” They went down Sixteenth Street and immediately WHRRRR, you could hear the motorcycles rev up and start out after them. Then the police arrested them.

While they were busy doing that, the leaders gave us signs and told us to go out Sixth Avenue in the opposite direction. The police thought the first group was all there was going to be that day. So my group got downtown to Newberry's. It was the first time we got all the way there. When the police realized what had happened, someone called the paddy wagon. They lined us up and snatched our signs from us.

There was one well-dressed old white lady who walked up to me. She said, “Why don't you niggers go back to the North. The niggers here is satisfied.” I will never forget that. She didn't know who we were. You know, they called it “northern interference.” They didn't have sense enough to know that we were not from the North. We were from right here. They thought we didn't have enough guts to do that, so it had to be someone from the North. She didn't touch me or spit on me. She just made that statement nd walked off.

Then they hauled us off to jail. In jail we would have prayer meeting in the mornings and at twelve and at night. Prayers from your heart, and freedom songs and Negro hymns. One night when we were in jail, they bombed the Gaston Motel. We were singing before the explosion. We heard the noise and knew something was bombed, but we didn't know what. The police got on the P.A. system and started singing “I Wish I Was in Dixie” over and over. But we didn't lose a beat. We just continued to sing our songs.

At the mass meetings people would say, “I can't go to jail, but here's a couple of dollars. Get yourself something to eat.” Or they'd bake a cake and bring it down to the church. If you had gone to jail you were somebody. People would always come up to you and say, “I wish I was you, but I can't.” We felt real good about it. I think that's what helped with a lot of the fear, people supporting you. They'd talk to you as if it were an honor to talk to someone who'd gone to jail.

Â

I remember one march very well. We met at New Pilgrim Church that Sunday. Immediately after the service we lined up in two's to march to Memorial Park, directly across from the City Police Department. This particular Sunday we had children and people of all ages. When we got to Memorial Park, Bull Connor was there. The Birmingham fire department was all ready with their hoses. That hose was so long, they had a line of firemen holding it every so many feet. And the policemen were there with their dogs. The dogs were on leashes. They'd lunge, and the police would pull them back. They thought it was funny to let them almost get to us. We were afraid of the dogs, but we were not to show fear. We were to keep walking and singing as if they were not there.

When we got to Memorial Park, Reverend Billups was standing in front of the group, and he said, “We are ready for your fire hoses, your dogs, and anything else!” And tears just started running down his face. I'll never forget it. Bull Connor told the firemen, “Turn the water on! Turn the water on!” But they stood there frozen. “Turn the water on! Turn the water on!” Then he started using profanity, cursing them, shaking the hose and shaking them. “Turn the hose on! Turn it on!” But those people just stood there. They would not turn the hoses on that Sunday. Then the whole group started singing Negro spirituals. It was just something in the air.

THE AFTERMATH:THE MARCH ON WASHINGTON AND THE SUNDAY SCHOOL BOMBING

In May 1963, the children had marched, been arrested, and spent time in jail. There was a feeling of triumph, of having acted on your beliefs, of having been a part of change.

The powerful momentum of the civil rights movement coming out of the Birmingham events reached a high point on August 28 of that year. From all over the country a quarter of a million people of all races, religions, and national backgrounds marched on Washington, D.C., in a protest demonstration to end discrimination against blacks. More than two thousand buses, thirty special trains, and thousands of automobiles poured into the capital. It was a sunny day, and people walked the demonstration route from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial with a sense of enjoyment as well as excitement.

The March on Washington had been planned by A. Philip Randolph, head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and Bayard Rustin, longtime civil rights activist. All the major civil rights groups helped coordinate the event, and all of the groups' leaders spoke. Dr. Martin Luther King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, in which he told of his vision that “my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” That was in August.

In September, there was tragedy. At a Sunday service at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, a bomb exploded, killing four young black girls, Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Cynthia Wesley, and Carole Robertson. The evil of racism was clear to the world. It could not be hidden behind a sentimental notion of a “southern way of life.”

The horror of the bombing affected all decent people, white as well as black. Charles Morgan, a white lawyer, gave a speech in Birmingham the day after the bombing. He asked, “Who did it? ... We all did it ... every person in this community who has in any way contributed ... to the popularity of hatred is at least as guilty ... as the demented fool who threw that bomb.”

Young people were deeply moved by the event. Audrey Faye Hendricks, Mary Gadson, and Bernita Roberson knew several of the girls who were killed.

AUDREY FAYE HENDRICKSI was at church at the time, and they came and told my pastor. He let us know that there had been a bombing at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. People were real upset. They cried. I cried. Later on that night I learned that the girls had died. I wondered how could somebody be so hate-filled about color. I remember seeing Denise's mother at school one day after they had buried her. I don't think she ever taught again. Denise was an only child.

MARY GADSONI went to school with two of the girls who were killed at the Sixteenth Street bombing. Cynthia Wesley and I sang in the Ullman High School choir together. Denise McNair was at Center Street school with me, although she was younger than I was. Her mother taught me at that school.

I was at home getting ready to go to church when I heard the news on the radio. My whole family was at home. The lady next door called my mama to ask her to turn on the TV. She did, and they had the news report about it. My mama was crying. We all started crying. It was just like family. They told us that as far as they could tell there were some deaths, but at that time they didn't know how many. Then the report came later that it was four girls that had been killed.

It was truly shocking. One of my girlfriends was in the same Sunday school class that morning with the girls. When the bomb went off, the head of one of the girls passed straight in front of her. My girlfriend had to go for psychiatric help. She didn't get hurt physically.

I couldn't believe anybody would do something like that at a church. We knew they had bombed houses and cars. That was nothing new. But when you take it out of the street and into the church, it was like nothing was sacred anymore.

BERNITA ROBERSONWhen the bomb went off, we felt it in our Sunday school class four blocks away. I lived across the street from Bethel Baptist [Reverend Shuttlesworth's church], so that I knew the feeling of a bomb. In about fifteen minutes, word got to us that they had bombed Sixteenth Street, where the children were in Sunday school. Then our Sunday school immediately turned out, and everybody got together in prayer.

I was a friend of Denise McNair. I knew her grandfather. He owned a cleaners, and I knew her from there. I was a flower girl for her funeral. Three of the funerals were held at the same time. There was nothing like seeing those three families there, and the three coffins. I was just trying to understand how somebody could do this to children. To this day, I don't really know.

I wasn't angry because you were taught not to be. You were taught to forgive people. Things were happening so fast during that time, you didn't know what to expect next. Anger and sorrow were just a part of trying to get accomplished what you wanted.

Following page:

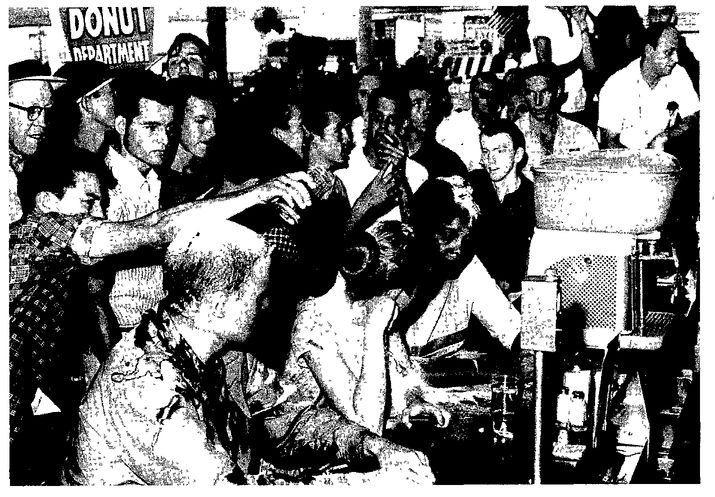

In Jackson, Mississippi, whites pour sugar, ketchup and mustard over the heads of restaurant lunch counter sit-in demonstrators in June, 1963.

In Jackson, Mississippi, whites pour sugar, ketchup and mustard over the heads of restaurant lunch counter sit-in demonstrators in June, 1963.

6â The Closed Society: Mississippi and Freedom Summer

Mississippi stood out even among southern states for its brutal enforcement of segregation. Almost half the population of the state was black, and there were more beatings, “disappearances,” and lynchings than in any other state in the nation. Mississippi was a “closed society,” as many called it.

In 1955 the rest of America woke up one morning to headlines about a singularly brutal killing. Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old boy from Chicago, had been visiting relatives in Mississippi when he was tortured and murdered for allegedly talking “improperly” to a white woman. In a segregated Mississippi courthouse, two white men were tried for the murder and acquitted. Several months later, they admitted to an Alabama journalist that they had indeed murdered Till.

Other books

Death Bringer (Soul Justice) by Pearce, Kate

Lucy Muir by The Imprudent Wager

The Chinaman by Stephen Leather

So Close to You (So Close to You - Trilogy) by Rachel Carter

Devious by Lisa Jackson

The Dictator by Robert Harris

Dolphin Island by Arthur C. Clarke

Forbidden Fruit by Anne Rainey

See Me by Pauline Allan

The Secret Diaries of Charlotte Brontë by Syrie James