Freeglader (24 page)

‘Glade-eater, eh?’ he said. ‘I like the sound of that.’ He smiled unpleasantly. ‘I'll give you old'uns, the sick and the lame, and that's my final offer. As for my finest tufteds and black-ears, they're needed for battle. The Furnace Masters aren't getting their sooty hands on

them

!’

A murmur of agreement went round the table. Hemtuft nodded sagely. ‘I'll send our third-borns,’ he said. ‘They never make the finest warriors anyway.’

‘No hammerheads, but I can spare some flat-heads,’ said Lytugg. ‘Strictly for guard-duty, you understand.’

‘Good,’ smiled Hemtuft. ‘How about you, Nectarsweet?’

‘I suppose I can spare a colony or two of gnokgoblins,’ she replied, the rolls of fat beneath her chins bouncing about as she spoke. ‘But I need my gyle goblins, every one of them. They're my babies …’ Tears sprang to her tiny eyes.

‘Yes, yes,’ said Hemtuft, turning to Meegmewl. ‘You heard the sacrifices the other clans are prepared to make,’ he said sternly. ‘Now it is the turn of the lop-ear clan.’

Meegmewl sighed. ‘I've already sacrificed too many a pink-eye and grey,’ he said. He shook his head. ‘The mood in the clan villages is turning ugly…’

‘Pah!’ said Lytugg scornfully. ‘Is the great clan chief, Meegmewl the Grey, frightened of his own goblins?’

Meegmewl looked down at the table. Hemtuft laid a hand on his shoulder.

‘What about your low-bellies, old friend?’ he said, smiling. ‘They're a good-natured, docile lot – and there's plenty of them. I'm sure Lytugg can lend you some of her flat-heads to round them up.’

Lytugg nodded. ‘

Ah, yes, the low-bellies,’ said Meegmewl quietly. He sighed again. ‘I suppose you're right, though I don't like it. I don't like it at all. Good-natured, docile creatures they may be, but even a low-belly can be pushed too far.’

Hemtuft raised his goblet. ‘To the glade-eater!’ he roared.

‘Now, friends of the harvest, let us gather round the table and each say our piece.’

‘It's not a table!’ someone shouted. ‘It's a hay-cart!’

‘Move over!’

‘Who are you pushing?’

Lob and Lummel Grope were attempting to bring a meeting of their own to order. Having attended Hemtuft Battleaxe's great assembly of the clans in the long-hairs' open-sided clan hut, they knew more or less what to do. The trouble was, no one else did.

‘Friends,’ said Lob, in a loud whisper. ‘Please! If we all speak at once, no one will be heard.’

‘S'not fair, so it isn't and that's a fact,’ said an old low-belly, scratching his swollen stomach through the grubby fabric of his belly-sling.

‘S'always us,’ another piped up, his straw bonnet jiggling about on his head. ‘An' I for one have had enough of it.’

‘I've lost a father, two brothers, eight cousins …’ broke in a third heatedly.

‘No one cares a jot about us…’

The babble of voices rose, with everyone trying to speak at the same time and no one able to hear anyone else. It was punctuated by occasional knocks on the barn-door, as others arrived to join the meeting. Lummel raised his hand to restore order. The last thing they wanted was to get into a shouting match and attract the attention of a flat-head patrol. But feelings were running high.

Word of Hemuel Spume's latest demands had gone round the Goblin Nations like wildfire, and it wasn't only the lop-ears in the western farmlands who were protesting. Goblins from all over were covertly whispering, one to the other, that enough was enough, and the meeting in the old wicker barn was getting larger and more unwieldy all the time.

‘Who goes there?’ bellowed a low-belly with a stubbly chin and a pitchfork, menacingly raised as yet another visitor knocked on the door.

‘A friend of the harvest,’ came the hissed reply. ‘Let me in.’

The door was unbolted and pulled back. The newcomer – a young tufted goblin with a jagged-toothed sabre and an ironwood shield – poked his head inside.

‘Enter, friend,’ the low-belly guard said. ‘But leave your weapon outside.’

The tufted goblin did as he was told and went in. A moment later, the guard was admitting a sick-looking tusked goblin, and a trio of garrulous gnokgoblins.

‘Friends …’ Lob shouted, his call lost among the rising cacophony of voices.

‘I mean, we've only got half the harvest in,’ someone was complaining. ‘Are we expected to leave the rest in the fields to rot?’

‘It just don't seem to occur to them that we all gotta eat!’

‘War, war, war – tha's all they ever seem to talk about.’

‘Friends, one and all!’ Lummel called out. ‘We must band together…’

But no one heard him. Of course, it didn't help that each and every one of the gathered goblins was tucking in to the woodapple cider that they had discovered was being stored in the barn. In the end, it was an old tusked goblin who took it upon himself to impose some kind of order on the proceedings. He strode to the front, where Lob and Lummel were now standing on top of the hay cart, and bellowed for quiet, before collapsing and calling for a swig of cider.

Shocked, the gathering of goblins fell silent. All eyes turned to the front.

‘Thank you, friends,’ said Lob, humbly. He turned to face the expectant crowd. ‘We have all lost loved ones to the Foundry Glades,’ he began.

‘And soon the flat-head guards will come for us,’ Lummel continued. ‘Low-belly, gnokgoblin, long-hair and tusked, young and old, frail and sick!’

The crowd murmured, heads nodding. ‘But what can we do?’ called out a gnokgoblin.

‘We must work together,’ said Lob.

‘We must help each other,’ said Lummel.

A muttering got up in the crowd as the two brothers' words sank in. They made sense, and the goblins started offering help to one another, suggesting places where those who were on the lists for the Foundry Glades might safely be concealed. As the noise began to rise once more, Lummel raised his hand for quiet.

‘We all know what this is about,’ said Lob, as the noise abated. ‘The clan chiefs want a war against the Free Glades, a war that'll make them rich. That much is clear. But why should

we

fight the Freegladers? Do not all of us have friends and relations who live among them?’

A murmur of assent went round.

‘What quarrel have the Goblin Nations with the Free Glades?’ Lummel added. ‘Why, their mayor is a goblin. A low-belly goblin! Hebb Lub-drub is his name.’ He paused, to let the words sink in. ‘A low-belly goblin, mayor of New Undertown.’ He shook his head. ‘Do any of us here want to help destroy such a place?’

For a moment there was silence. Then, tentatively at first, but with growing conviction, voices from all round the old wicker barn answered.

‘No…’

‘No…’

‘No!’

Lob and Lummel looked at one another and grinned. It was a start. A good start.

iii New Undertown

As darkness fell, Mother Bluegizzard – fresh from her afternoon nap – flapped round the tavern, a long flaming taper in her claws, lighting the lamps and greeting her faithful old regulars as she went. It was only when she got to the far corner that she realized one of them was missing.

She nodded towards the empty table. ‘No Mire Pirate again tonight?’ she asked.

Zett shrugged. ‘Doesn't look like it,’ he said.

‘Haven't seen him all week,’ added Grome, scratching his great hairy chest with all fingers as he spoke.

Mother Bluegizzard frowned, her neck ruff trembling. ‘Most peculiar,’ she commented. ‘I wonder where he's got to.’

Meggutt, Beggutt and Deg poked their heads up out of their drinking trough, one after the other.

‘We ain't seen him, neither,’ they said. ‘Not hide nor hair.’

The old bird-creature lit the last lantern and blew out the taper. ‘I hope he's all right,’ she said. ‘Place doesn't seem the same without him.’

The others all nodded. None of them had ever heard the old Mire Pirate utter so much as a word, yet his empty table seemed to make the tavern even quieter than usual. Even Fevercule had no idea. They returned to their drinks.

In fact, if any of the regulars had bothered to look,

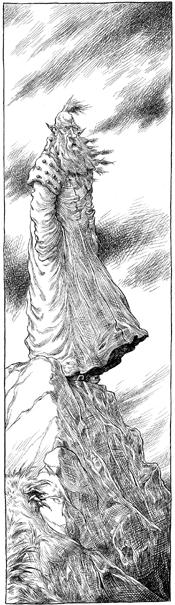

they'd have discovered that the Mire Pirate wasn't far from the Bloodoak Tavern at all. The dishevelled old sky pirate, with his great bushy beard and haunted eyes, was standing on a small hill screened by lufwood trees, but with a clear view of the North Lake jetty below. He'd been coming to this exact same spot for a week now, standing and staring, as silent as a statue, through the long moonless nights until dawn broke above Lullabee Island. Then, each morning, he'd turn and trudge silently away, only to return the next night.

This night was no exception. The Mire Pirate stood on the secluded hill top and stared over at the island in the lake and waited. He waited as the moon rose, clouds drifted across the sky and the hawkowls hooted. He waited as the

moon sank and another dawn broke. He was just about to turn away and trudge back to New Undertown once more, when a distant splash made him hesitate.

As he watched, a small coracle bobbing on the water made its way from the island to the jetty. He raised a hand to his mouth, as if stifling a cry, and was about to descend the hill when he noticed a small group hurrying towards the North Lake jetty below.

The Mire Pirate checked himself and waited.

‘There he is!’ shouted a youth in a bleached muglump-skin jacket, and the three banderbears beside him yodelled out across the water.

The

splash-splash

of the paddles increased as the coracle approached the shore. With the help of its crew of turquoise-clad oakelves, a librarian climbed from the little boat and onto the jetty.

‘Rook!’ Felix exclaimed. ‘At last! There you are!’

‘Good morning, Felix!’ Rook smiled, clasping his friend's hand and shaking it vigorously.

The banderbears yodelled and gesticulated in delight. The oakelves smiled and, without saying a word, pushed off from the jetty and began the journey back to Lullabee Island.

‘All week, we've been waiting,’ said Felix. ‘All week! I was beginning to wonder if you were

ever

going to return! But, my word!’ He let go of Rook's hand and stared into his face. ‘It seems to have done you the power of good, by the look of you, Rook!’

‘A week?’ said Rook, shaking his head in disbelief. ‘I've been asleep in the caterbird cocoon for a whole week!’

‘Caterbird cocoon?’ said Felix. It was his turn to look amazed. ‘So that was the miracle cure, was it? Why, those clever old oakelves. We were right to trust them after all, weren't we, fellas?’

The banderbears yodelled their agreement.

‘Now, we're wanted at Lake Landing, Rook,’ said Felix, clapping him on the back. ‘Absolute hive of activity it is. But you'll see what I mean when we get there.’ He laughed and pulled Rook after him. ‘Come, it's a fine morning for a stroll and you can tell us all about the dreams you had in this caterbird nest of yours – a whole week's worth!’

As the small group made off, the old sky pirate emerged from behind the lufwood trees. He watched them for a moment, his pale eyes misted with tears. His lips moved and in a voice deep and gravelly from lack of use, he whispered one word.

‘Barkwater.’

• CHAPTER THIRTEEN •

TEA WITH A SPINDLEBUG

D

espite the early hour, the Gardens of Light were far from still. Spindlebug gardeners with long rakes and stubby hoes patrolled the walkways between the fungus fields, tending to the pink, glowing toadstools. Milchgrubs, their huge udder-sacs sloshing and slewing with pink liquid, grazed contentedly. Slime-moles snuffled round their pits, trying to find any uneaten scraps from their last feed; while all round the illuminated caverns, crystal spiders and venomous firemoths strove to keep out of one another's way.

Up above, in the Ironwood Glade, there was no moon and the sun had not yet risen. Apart from the occasional snorts and cries of the prowlgrins roosting in the branches of the tall trees, the place was silent. The fromps and quarms were sleeping, and the predatory razorflits had not yet returned from a night of hunting.

Suddenly, breaking the stillness and illuminating a

patch of dark forest floor with light, a column of several dozen gyle goblins appeared. They were fresh from a successful foraging trip collecting moon-mangoes – large, pink-blushed fruits that ripened at night and had to be picked immediately if their succulent flesh was not to turn sour. Walking in single file, the gyle goblins made their way to the centre of the Ironwood Glade where a well-like hole in the ground was situated. They stopped, swung the baskets down and, one after the other, tipped their contents down the hole.