French Powder Mystery (2 page)

Read French Powder Mystery Online

Authors: Ellery Queen

Which leaves me little else to write but a most sincere hope that you will enjoy the reading of

The French Powder Mystery

fully as much as I did.

J. J. McC.

NEW YORK

June, 1930

ENCOUNTERED IN THE COURSE OF THE FRENCH INVESTIGATION

*

NOTE:

A list of the personalities involved in The French Powder Mystery is here set at the disposition of the reader. He is urged indeed to con the list painstakingly before attacking the story proper, so that each name will be vigorously impressed upon his consciousness; moreover, to refer often to this page during his perusal of the story. … Bear in mind that the most piercing enjoyment deriving from indulgence in detectival fiction arises from the battle of wits between author and reader. Scrupulous attention to the cast of characters is frequently a means to this eminently desirable end.

Ellery Queen

WINIFRED MARCHBANKS FRENCH,

Requiescat in pace.

What cesspool of evil lies beneath her murder?

BERNICE CARMODY,

a child of ill-fortune.

CYRUS FRENCH,

a common American avatar—merchant prince and Puritan.

MARION FRENCH,

a silken Cinderella.

WESTLEY WEAVER,

amanuensis and lover—and friend to the author.

VINCENT CARMODY,

l’homme sombre et malheureux.

A dealer in antiquities.

JOHN GRAY,

director. A donor of book-ends.

HUBERT MARCHBANKS,

director. Ursine brother to the late Mrs. French.

A. MELVILLE TRASK,

director. Sycophantic blot on a fair ’scutcheon.

CORNELIUS ZORN,

director. An Antwerpian nabob, potbelly, inhibitions and all.

MRS. CORNELIUS ZORN,

Zorn’s Medusa-wife.

PAUL LAVERY,

the impeccable

français.

Pioneer in modern art-decoration. Author of technical studies in the field of fine arts, notably

L’Art de la Faïence, publié par Monserat, Paris, 1913.

ARNOLD MACKENZIE,

General Manager of French’s, a Scot.

WILLIAM CROUTHER,

chief guardian of the law employed by French’s.

DIANA JOHNSON,

a model of fear.

JAMES SPRINGER,

Manager of the Book Department, a mysterioso.

PETER O’FLAHERTY,

leal head nightwatchman of the French establishment.

HERMANN RALSKA, GEORGE POWERS, BERT BLOOM,

night-watchmen.

HORTENSE UNDERHILL,

genus

housekeeper tyranna.

DORIS KEATON,

a maidenly minion.

THE HON. SCOTT WELLES,

just a Commissioner of Police.

DR. SAMUEL PROUTY,

Assistant Medical Examiner of New York County.

HENRY SAMPSON,

District Attorney of New York County.

TIMOTHY CRONIN,

Assistant District Attorney of New York County.

THOMAS VELIE,

Detective-Sergeant under the wing of Inspector Queen.

HAGSTROM, HESSE, FLINT, RITTER, JOHNSON, PIGGOTT,

sleuths attached to the command of Inspector Queen.

SALVATORE FIORELLI,

Head of the Narcotic Squad.

“JIMMY,”

Headquarters fingerprint expert who has ever remained last-nameless.

DJUNA,

The Queens’ beloved scull, who appears far too little.

Detectives, policemen, clerks, a physician, a nurse, a Negro caretaker, a freight watchman, etc., etc., etc., etc.

and

INSPECTOR RICHARD QUEEN

who, being not himself, is sorely beset in this adventure

and

ELLERY QUEEN

who is so fortunate as to resolve it.

*

The success of this device in his recent novel

(The Roman Hat Mystery)

has encouraged Mr. Queen to repeat it here. It was found useful by many of Mr. Queen’s readers in keeping the

dramatis personal

compactly before them.—

THE EDITOR.

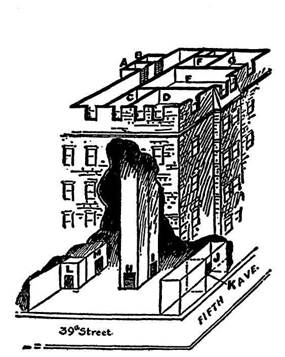

A—Elevator shaft

B—Stairway shaft

C, D, E, F, G—French apartment

C—Lavatory

D—Bedroom

F—Anteroom

E—Library

G—Cardroom

H—Ground floor door to elevator, facing 39th Street corridor

I—Ground floor to stairway, facing Fifth Avenue corridor

J—Window containing Lavery Exhibition

K—Door to murder-window

L—O’Flaherty’s office, with view of 39th Street entrance

M—Door from freight room

“Parenthetically speaking … in numerous cases the sole difference between success and failure in the detection of crime is a sort of … osmotic reluctance (on the part of the detective’s mental perceptions) to seep through the cilia of

WHAT SEEMS TO BE

and reach the vital stream of

WHAT ACTUALLY IS.”

From

A PRESCRIPTION FOR CRIME,

By

Dr. Luigi Pinna

“The Queens Were in the Parlor”

T

HEY SAT ABOUT THE

old walnut table in the Queen apartment—five oddly assorted individuals. There was District Attorney Henry Sampson, a slender man with bright eyes. Beside Sampson glowered Salvatore Fiorelli, head of the Narcotic Squad, a burly Italian with a long black scar on his right cheek. Red-haired Timothy Cronin, Sampson’s assistant, was there. And Inspector Richard Queen and Ellery Queen sat shoulder to shoulder with vastly differing facial expressions. The old man sulked, bit the end of his mustache. Ellery stared vacantly at Fiorelli’s cicatrix.

The calendar on the desk nearby read Tuesday, May the twenty-fourth, 19—. A mild spring breeze fluttered the window draperies.

The Inspector glared about the board. “What did Welles ever do? I’d like to know, Henry!”

“Come now, Q, Scott Welles isn’t a bad scout.”

“Rides to hounds, shoots a 91 on the course, and that makes him eligible for the police commissionership, doesn’t it? Of course, of course! And the unnecessary work he piles on us. …”

“It isn’t so bad as that,” said Sampson. “He’s done some useful things, in all fairness. Flood Relief Committee, social work. … A man who has been so active in non-political fields can’t be a total loss, Q.”

The Inspector snorted. “How long has he been in office? No, don’t tell me—let me guess. Two days. … Well, here’s what he’s done to us in two days. Get your teeth into this.

“Number one—reorganized the Missing Persons Bureau. And why poor Parsons got the gate

I

don’t know. … Number two—scrambled seven precinct-captains so thoroughly that they need road maps to get back to familiar territory. Why? You tell me. … Number three—shifted the make-up of Traffic B, C, and D. Number four—reduced a square two dozen second-grade detectives to pounding beats. Any reason? Certainly! Somebody whose grand-uncle’s niece knows the Governor’s fourth secretary is out for blood. … Number five—raked over the Police School and changed the rules. And I know he has his eagle eye on my pet Homicide Squad. …”

“You’ll burst a blood-vessel,” said Cronin.

“You haven’t heard anything yet,” said the Inspector grimly. “Every first-grade detective must now make out a daily report—in line of duty, mind you—a daily personal report direct to the Commissioners office!”

“Well,” grinned Cronin, “he’s welcome to read ’em all. Half those babies can’t

spell

homicide.”

“Read them nothing, Tim. Do you think he’d waste

his

time? Not by your Aunt Martha. No, sir! He sends them into

my

office by his shiny little secretary, Theodore B. B. St. Johns, with a polite message: ‘The Commissioner’s respects to Inspector Richard Queen, and the Commissioner would be obliged for an opinion within the hour on the veracity of the attached reports.’ And there I am, sweating marbles to keep my head clear for this narcotic investigation—there I am putting my mark on a flock of flatfoot reports.” The Inspector dug viciously into his snuff-box.

“You ain’t spilled half of it, Queen,” growled Fiorelli. “What’s this wall-eyed walrus, this pussy-footing specimen of a ‘civvie’ do but sneak in on my department, sniff around among the boys, hook a can of opium on the sly, and send it down to Jimmy for—guess what—fingerprints! Fingerprints, by God! As if Jimmy could find the print of a dope-peddler after a dozen of the gang had had their paws on the can. Besides, we had the prints already! But no, he didn’t stop for explanations. And then Stern searched high and low for the can and came runnin’ to me with some crazy story that the guy we’re lookin’ for’d walked himself straight into Headquarters and snitched a pot of opium!” Fiorelli spread his huge hands mutely, stuck a stunted black cheroot into his mouth.

It was at this moment that Ellery picked up a little volume with torn covers from the table and began to read.

Sampson’s grin faded. “All joking aside, though, if we don’t gain ground soon on the drug ring we’ll all be in a mess. Welles shouldn’t have forced our hand and stirred up the White test case now. Looks as if this gang—” He shook his head dubiously.

“That’s what riles me,” complained the Inspector. “Here I am, just getting the feel of Pete Slavin’s mob, and I have to spend a whole day down in Court testifying.”

There was silence, broken after a moment by Cronin. “How did you come out on O’Shaughnessy in the Kingsley Arms murder?” he asked curiously. “Has he come clean?”

“Last night,” said the Inspector. “We had to sweat him a little, but he saw we had the goods on him and came through.” The harsh lines around his mouth softened. “Nice piece of work Ellery did there. When you stop to think that we were on the case a whole day without a glimmer of proof that O’Shaughnessy killed Herrin, although we were sure he’d done it—along comes my son, spends ten minutes on the scene, and comes out with enough proof to burn the murderer.”

“Another miracle, eh?” chuckled Sampson. “What’s the inside story, Q?” They glanced toward Ellery, but he was hunched in his chair, assiduously reading.

“As simple as rolling off a log,” said Queen proudly. “It generally is when he explains it.—Djuna, more coffee. Will you, son?”

An agile little figure popped out of the kitchenette, grinned, bobbed his dark head, and disappeared. Djuna was Inspector Queen’s valet, man-of-all-work, cook, chambermaid, and unofficially the mascot of the Detective Bureau. He emerged with a percolator and refilled the cups on the table. Ellery grasped his with a questioning hand and began to sip, his eyes riveted on the book.

“Simple’s hardly the word,” resumed the Inspector. “Jimmy had sprinkled that whole room with fingerprint powder and found nothing but Herrin’s own prints—and Herrin was deader than a mackerel. The boys all took a whack at suggesting different places to sprinkle—it was quite a game while it lasted. …” He slapped the table. “Then Ellery marched in. I reviewed the case for him and showed him what we’d found. You remember we spotted Herrin’s footprints in the crumbled plaster on the dining-room floor. We were mighty puzzled about that, because from the circumstances of the crime it was impossible for Herrin to have been in that dining-room. And that’s where superior mentality, I suppose you’d call it, turned the trick. Ellery said: ‘Are you certain those are Herrin’s footprints?’ I told him they were, beyond a doubt. When I told him why, he agreed—yet it was impossible for Herrin to have been in that room. And there lay the prints, giving us the lie. ‘Very well,’ says this precious son o’ mine, ‘maybe he wasn’t in the room, after all.’ ‘But Ellery—the prints!’ I objected. ‘I have a notion,’ he says, and goes into the bedroom.

“Well,” sighed the Inspector, “he certainly did have a notion. In the bedroom he looked over the shoes on Herrin’s dead feet, took them off, got some of the print powder from Jimmy, called for the copy of O’Shaughnessy’s fingerprints, sprinkled the shoes—and sure enough, there was a beautiful thumb impression! He matched it with the file print, and it proved to be O’Shaughnessy’s. … You see, we’d looked in every place in that apartment for fingerprints except the one place where they were—on the dead body itself. Who’d ever think of looking for the murderer’s sign on his victim’s shoes?”

“Unlikely place,” grunted the Italian. “How’d it figure?”

“Ellery reasoned that if Herrin wasn’t in that room and his shoes were, it simply meant that somebody else wore or planted Herrin’s shoes there. Infantile, isn’t it? But it had to be thought of.” The old man bore down on Ellery’s bowed head with unconvincing irritability. “Ellery, what on earth are you reading? You’re hardly an attentive host, son.”

“That’s one time a layman’s familiarity with fingerprints came in handy,” grinned Sampson.

“Ellery!”

Ellery looked up excitedly. He waved his book in triumph, and began to recite to the amazed group at the table: “If they went to sleep with the sandals on, the thong worked into the feet and the sandals were frozen fast to them. This was partly due to the fact that, since their old sandals had failed, they wore untanned brogans made of newly flayed ox-hides.

*

Do you know, dad, that gives me a splendid idea?” His face beamed as he reached for a pencil.