Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream (27 page)

Read Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream Online

Authors: H. G. Bissinger

Tags: #State & Local, #Physical Education, #Permian High School (Odessa; Tex.) - Football, #Odessa, #Social Science, #Football - Social Aspects - Texas - Odessa, #Customs & Traditions, #Social Aspects, #Football, #Sports & Recreation, #General, #United States, #Sociology of Sports, #Sports Stories, #Southwest (AZ; NM; OK; TX), #Education, #Football Stories, #Texas, #History

West

I

I

THE NIGHT BEFORE THE FOURTH GAME OF THE SEASON AGAINST

Odessa High, Gaines locked the doors of the field house for a

team meeting. Private gatherings such as this were not held

very often-only when the idea of defeat became not only unthinkable but intolerable. Losing to the cross-town rival from

the west was one of those situations, a possibility even more

horrid to Permian fans than that of Michael Dukakis becoming

president.

To put the game into perspective and draw the proper parallels, Gaines told the players the story of Sam Davis.

Davis had been a Confederate scout during the Civil War

when he came face to face during battle with a scout from the

Union army. With the battle over for the day they sat in the

moonlight and talked, and before they parted the Union scout

revealed secrets about his own army's position. When Davis was

subsequently captured by Union forces, he was told he could

go free if he revealed the name of the person who had given

him the information. But Davis had no interest in such a lowhanded compromise. "I would die a thousand deaths before I

would betray a friend" were his final words.

It was a vignette that was deemed appropriate on the occasion of the Odessa High game, much like the quotation from

H. L. Mencken that had been posted on the field house bulletin

board:

Every normal man must be tempted, at times, to spit on his hands,

hoist the black ling, and begirt slitting throats.

The boys in front of Gaines, out of uniform and away from

the hue and cry usually sparked by their appearance, looked

strangely vulnerable. Dressed in blue jeans and short-sleeved

shirts and well-shined cowboy boots, their hair neatly combed

and their eyes still capable of expressing admiration for stories

such as this, it was one of those rare moments when it suddenly became apparent that they were nothing more than high

school kids.

°I am sure there are many applications that can be drawn

from that little story," said Gaines of Sam Davis's eager willingness to die. "The main applications I get from it are twofold.

One is friendship, and the second one is loyalty.

"We've got a big challenge ahead of us tomorrow night. I

want us to play like fifty-two brothers. All for one and one for

all. I want us to have that cohesiveness, that unified spirit. Fiftytwo people pulling together is hard to beat, men. Fifty-two

brothers are hard to beat.

"We know that OHS is going to be fired to the hilt and I want

to match them emotion for emotion.... It's gonna be a big

crowd. It's an exciting game. 1 wish everybody that has an opportunity to play the game of football all over the United States

had an opportunity to play in a game like this. You're part of a

select group."

As part of the tradition in these meetings, Gaines and the

other coaches then left the room so the captains could address

the players privately.

"I don't care what they think over there," said Ivory Christian. "We oughta just run over them like sixty-two to nothin' or

somethin'. We oughta blow 'em out. I don't think they can stay

on the field with us, man. We play hard like we always do on

Friday night..... We know how they are, the first quarter you

start hittin 'em a couple of times, get a couple of sticks on 'em,

they want to quit."

The next afternoon, the players filtered into the field house to get dressed and have final pre-game meetings. "I don't want

you gettin' blocked by a finesse block. If you get blocked, it better be by a macho man," Coach Belew told the defensive ends.

"I want one hell of a wreck out there. I want that boy to be

sorry he's playin'. Run upfield like a scalded dog. Run upfield

and contain that sucker."

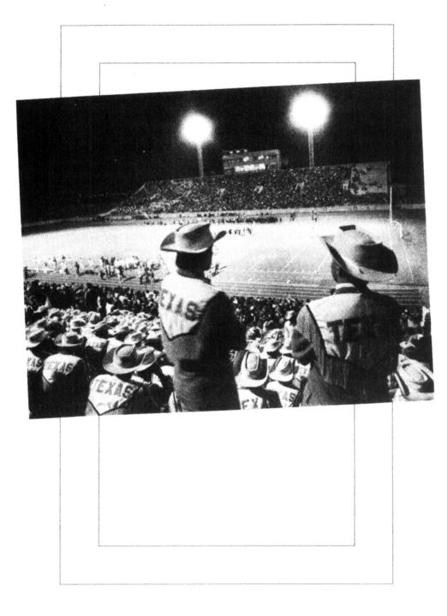

By game time more than fifteen thousand fans had emptied

into Ratliff Stadium, where a full moon, luscious and plump,

sweetened the languid desert night and turned the sky an incandescent blue. On one side were the Odessa High fans,

dressed in red, ready for this to be the year when the jinx was

finally broken, when they joyously shed the yoke of football

famine that had caused them so much embarrassment and

so many feelings of inferiority. On the other side were the

Permian fans, dressed in black, arms folded, looking like highand-mighty music teachers listening to the annual school recital, so used to superlative achievement from their star pupils

that only the most flawless performance would break their cold

impassivity.

The game began. The kickoff fluttered in the warm air amid

shrieks and screams. Permian's Robert Brown took the ball

and barely got to the 15 before he was smothered by a crowd

of Odessa High defenders. They slapped each other on the

helmet after the tackle and ran off the field with exuberance.

Maybe that opening kickoff was an omen. Maybe it meant that

parity had been reached, that tonight was the night for the west

side of Odessa to reach back into history, to show that it too

could excel at what mattered most.

Or maybe it meant nothing at all.

Ducking underneath the offensive line, Winchell took the

snap from center and handed the ball to Billingsley on a tackle

trap. He saw a hole and went for it.

The game was on....

There was no better metaphor for the town, no better way to

understand it-the rapidly changing demographics, the selfperpetuating notions of superiority that spread over one half and inferiority that spread over the other. The PermianOdessa High game had become a clash of values-between the

nouveau riche east side of town and the older, more humble

west, between white and Hispanic, between rich and poor,

between the suburban-style mall and the decrepit, decaying

downtown.

Twenty-three years.

Twenty-three lousy, painful, shitty years without beating Permian, worse than the plague of locusts, worse than rooting for

the Cubs, worse than the Dust Bowl droughts.

Although some had seen slight improvement in recent times,

there was no love lost between the two sides. Savannah Belcher,

who had her own show on cable television here and was the

closest thing Odessa had to Hedda Hopper, called the boundary line separating the two schools "the Mason Dixon line of

Odessa. They're not really at war, but a lot of those scars haven't

quite healed."

Each year there was always the dream that this was finally it,

the game where the juggernaut of Permian would somehow

self-destruct and the sheer emotion of Odessa High would

finally prevail. The possibility of that tantalized everyone,

whether they liked football or not.

Vickie Gomez was a perfect example. During her two terms

on the school hoard she had gotten more than her fill of sports,

and she wondered what good high school football did for the

kids who played it. But even Gomez had intense feelings about

the rivalry because of what a win over Permian would accomplish not only for Odessa High fans but the whole west side of

town-the side of town that seemed to have all the trailer

homes and the apartment courts made of glue and papier-

mache and the junkyards and the sealed-off areas filled with

the hulks of oil rigs that no one wanted anymore, the side of

town that had become identified with white oil field trash and

wetbacks up from the border.

In the forties and fifties, most Hispanics who trickled into

Odessa settled on the Southside. In the sixties and seventies and eighties, the influx of Hispanics rapidly increased and

many began living not only on the Southside but the west side

as well.

Nothing else in town, not even the resurgence of the oil industry in another frenzied boom, could give the west side the

same sort of psychological lift as a win over Permian. Even if

the feeling was momentary, it would put Odessa High on equal

footing with those east-siders who went home victorious time

after time after time to those sprawling ranch houses in those

sweet little cul-de-sacs with those names like something out of a

Gothic romance. But every time the Odessa Bronchos got close

something miraculously had happened-a fumble into the end

zone with the winning touchdown and no time left on the clock,

an unheard-of snowstorm turning a potent offense into mush.

It truly seemed as if' nothing less than fate herself was working against them, somehow had it in for the Bronchos, who

simply could not beat Permian no matter how hard they tried.

"I'm just living for the day that Odessa High beats Permian,"

said Vickie Gomez, the thought bringing a smile to her usually

serious lips. "That's the one thing I'm living for. I'm gonna get

out of this town, but not before that happens."

II

II