Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream (35 page)

Read Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream Online

Authors: H. G. Bissinger

Tags: #State & Local, #Physical Education, #Permian High School (Odessa; Tex.) - Football, #Odessa, #Social Science, #Football - Social Aspects - Texas - Odessa, #Customs & Traditions, #Social Aspects, #Football, #Sports & Recreation, #General, #United States, #Sociology of Sports, #Sports Stories, #Southwest (AZ; NM; OK; TX), #Education, #Football Stories, #Texas, #History

There were also times when his undisciplined running style

seemed wilder than ever, as if he was frantically trying, in a

single carry, to make up for an entire season that he knew was

fleeing from him.

II

II

There was hope now, and bit by bit, with each game, it had

gotten brighter and brighter. It still seemed impossible half the

time but it was there, a glowing speck like the last drop of the

sun on the horizon. Could he cradle it? Could he catch it?

Was it totally ridiculous to think of this skinny, earnest kid

wearing the orange and white of Texas next year? Maybe so.

Even Mike Winchell wondered how he could possibly compete with the studs that he read about over and over in the worn

pages of Texas Football magazine, guys from Hurst Bell and

Denison and Langham Creek who were taller and faster and

stronger, guys with discreet half-smiles on their faces who always looked as if there wasn't a thing in the world that could

ever get to them or rattle them.

Mike himself had a wonderful smile, but it suggested warmth

and innocence, not serene self-confidence in the face of all challenges. "I was kind of an oops," was the way he described his

entrance into the world. Sometimes he half jokingly suggested

that he should have gotten out of football back in Pop Warner

when he was at the top of his game. And yet, on days when he

was feeling good about himself and everything just seemed to

click, he knew he threw the ball with a special gift.

The Abilene Cooper game had been like that. It was all so

wonderfully, effortlessly easy. He already had had several great

games-the opener against El Paso Austin, the one against

Midland High-but this was his greatest. Midway in the first

quarter, when he had seen the Cooper cornerback go into motion before the play started, he knew they were going to be in

man-to-man. He looked for Hanker Robert Brown down the

right sideline and threw the ball crossfield on a dime about

forty yards. Brown caught it in stride for a sixty-two-yard

touchdown. In the second quarter, he lined up and saw the

Cooper secondary once again out of kilter. They were giving

Brown too much cushion, laying off him six or seven yards.

Once again he won the chess match and laid the ball in for a

nineteen-yard touchdown. Still in the same quarter, he lined up

over center and saw Cooper in one-on-one coverage against

Lloyd Hill. That was more idiotic than giving Robert Brown a

seven-yard cushion. The play immediately formed in his mind.

Hill ran a fly pattern and Winchell hit him for a forty-five-yard

touchdown. Still in the same quarter, he backpedaled, saw Robert Brown break free, and threw another touchdown pass, this

one good for eighteen yards.

By the time the first half ended, Winchell had thrown nine passes. Five had been incomplete. The other four had been for

touchdowns. He didn't throw any more passes that night, but it

hardly mattered. Through the first eight games of the season

he had thrown for seventeen touchdowns. Assuming Permian

got into the playoffs, which seemed automatic at that point, he

was destined to break the single-season record for most touchdown passes.

"Michael has had so many strikes against him, and has struggled so hard, you just want to see him succeed," said Deborah

Hargis, a social studies and history teacher at Permian. "There

just aren't a lot of good kids, and he's a good kid."

Like many who met him, she became both intrigued and

enchanted with him. She saw something rare there, and when

she thought of him a particular image often came floating back

to her.

The year before, when he had been in her history class, they

had held a Beautiful Baby contest. Mike brought in a picture

of himself, but it wasn't one of those smiling-from-ear-to-ear

shots taken at Sears or Penney's. Mike had never lived a life like

that. Instead he was holding a piece of gum while a single tear,

like the wispy trail of a jet, fell down his cheek. Mike explained

that he was crying because he had never seen a camera before

and thought it was a gun. Hargis always remembered that picture and the softness of those brown eyes as Mike apparently

thought he would be shot the second the shutter button clicked.

She loved the way he was with children, particularly those

who worshiped him and came to the school pep rallies wearing a jersey with his number, 20, on it. She loved the relationship he had with his grandmother, how he delighted in her

and always watched out for her. She loved the way he was a

klutz off the field despite his enormous athletic abilities, how he

invariably spilled food on himself when he went out to eat or

how when he got up from his desk in class one day he knocked

it over.

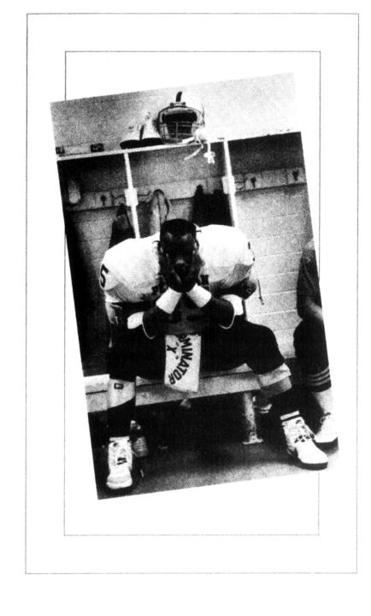

There were times when a dark cloud descended over him,

making him virtually silent. His face became filled with a look of sad, aching brooding, as if he was thinking about something

that only he could understand and somehow resolve. But there

were other tines when he became alive and animated, like a

child gingerly touching the edge of the ocean before plunging

in, displaying a curiosity unique among kids who lived in

Odessa.

New York, Philadelphia, the towering cities of the East beckoned to him with the exoticism of stories by Kipling, and he

wanted to know about them, to see if the things he had read in

magazines and saw on television were true. Were there muggers on every corner? Was there really a Mafia? The absolute

lack of guile in his voice as he wondered about places that

seemed to exist in a universe separate from the one he occupied in Odessa, the twinkle of a smile spreading over the

flat contours of his face, made it easy to see why his favorite

book, outside of the sports autobiographies he had read of Jim

McMahon and Ken Stabler and Reggie Jackson, was Huckleberry

Finn. Floating on a raft down the Mississippi to one mysterious

place after another with nothing else around except trees and

water, it beckoned to him. "I could stand to do that, go down

the river," he said.

As he probed and pawed about worlds so different from his

own, something in his own life would suddenly hit him-the

time he had gone deer hunting and had one in his sights but

couldn't bring himself to shoot it; another time when he had

camped out near the Devil's River down around Del Rio; fishing trips on the Pecos, where he and a friend went river rafting

on old tables they had found; the road trip with his brother to

the state high school football championship between Mart and

Shiner. He talked for a minute, or maybe two or maybe even

five, as if something inside him had been punctured, had been

unleashed and come alive again. And then, abruptly, the torrent stopped and his face once again regained its brooding

stare.

Hargis knew there were days when it was best to leave Mike

alone, when he seemed impervious to the emotional gestures of anyone. But there were also clays when her poking and prodding led to a small foothold inside him, a tiny ray of light inside

an intricate cavern with more depth than anyone could possibly

have realized.

She desperately wanted him to make it, as did everyone else

who had ever met him and become aware of some of the tidbits

of his past-the death of Billy, the way he refused to let virtually anyone inside his home, the way he had raised himself.

As Boobie's season became a sad and sour struggle, Mike

Winchell's only continued to rise. As Boobie tried to find the

natural rhythm of the year before, Mike edged closer and

closer to a dream he had quietly harbored for much of his life.

As they headed into the ultimate showdown against Midland Lee, they were two opposites, one plunging so fast he

could barely hold on anymore, the other soaring beyond all

expectations.

Led by Winchell, Permian trampled the Cooper Cougars

56- 14 to push its record to seven and one. Everywhere you

looked that night you saw a star-Winchell at quarterback,

Comer at fullback, Hill at split end, Brown at Hanker, Christian

at middle linebacker, Chavez at tight end-a team so damn

good it hadn't missed a single beat when Boobie had wrecked

his knee and went on without him as if he had never been

there. And every fan couldn't help but believe that the following week's game would be little more than a continuation of the

Cooper obliteration, only a thousand times more sweet.

It was hard to get too worked up over Abilene and the Cooper Cougars. They didn't look down their noses and act as if

Odessa was some sort of primeval desert wilderness with people

whose intellectual capacity fell somewhere between that of the

Goths and the Visigoths. No, there wasn't any reason in the

world to hold a grudge against Abilene.

But the same couldn't be said for Midland, which held a

unique place in the hearts of almost every Odessan. Even the

most liberal ones who had spent a lifetime fighting racial and social injustice and who cherished the notion of open-mindedness drew the line at the Midland border.

"Texans everywhere, except Midland, are tolerant of each

other," said Odessa attorney Michael McLeaish, still smarting

from the time he had gone as a kid to a party in Midland over

at the country club and walked around in it bow tie that began

to feel as big as a ski jump while everyone else looked so cool

and casual. "Midland is a principality. I don't like people from

Midland. They don't like us and we don't like them. I just can't

stand those bastards and they feel the same way about us."