Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream (7 page)

Read Friday Night Lights: A Town, a Team, and a Dream Online

Authors: H. G. Bissinger

Tags: #State & Local, #Physical Education, #Permian High School (Odessa; Tex.) - Football, #Odessa, #Social Science, #Football - Social Aspects - Texas - Odessa, #Customs & Traditions, #Social Aspects, #Football, #Sports & Recreation, #General, #United States, #Sociology of Sports, #Sports Stories, #Southwest (AZ; NM; OK; TX), #Education, #Football Stories, #Texas, #History

A year later, Odessa made national news again when someone

made the fateful mistake of accusing an escaped convict from

Alabama named Leamon Ray Price of cheating in a high-stakes

poker game. Price, apparently insulted by such a charge, went

to the bathroom and then came out shooting with his thirtyeight. He barricaded himself behind a bookcase while the players he was trying to kill hid under the poker table. By the time

Odessa police detective Jerry Smith got there the place looked

like something out of the Wild West, an old-fashioned shoot-out

at the La Casita apartment complex with poker chips and cards

and bullet holes all over the dining room. Two men were dead

and two wounded when Price made his escape. His fatal error

came when he tried to break into a house across the street. The

startled owner, hearing the commotion, did what he thought

was only appropriate: he took out his gun and shot Price dead.

It was incidents such as these that gave Odessa its legacy.

In 1987, Money magazine ranked it as the fifth worst city to

live in in the country out of three hundred. A year later Psychology Today, in a ranking of the most stressful cities in the

country based on rates of alcoholism, crime, suicide, and divorce, placed Odessa seventh out of 286 metropolitan areas,

worse than New York and Detroit and Philadelphia and Houston. Molly Ivins, a columnist for the Dallas Times Herald, described Odessa as an "armpit," which, as the Odessa American

pointed out, was actually quite a few rungs up from its usual anatomical comparison with a rectum. And there was the description in Larry McMurtry's Texasville, which simply called

Odessa the "worst town on earth."

But none of that seemed to matter. Oil promised money

through work on drilling rigs and frac crews and acidizing

units, and it meant people were willing to live here whatever

the deprivation. What pride they had in Odessa came from

their very survival in a place they openly admitted was physically wretched.

Whether it was true or not, most people said they had first

come out here during a sandstorm, meaning their first taste of

Odessa had literally been a mouthful of gritty sand. They carried that mouthful with them forever, rolling it around with

their tongues every now and then, never forgetting the dry grit

of it. It reminded them of what they had been through to forge

a life and a community and that they had a right to be proud

of their accomplishments.

It was still a place that seemed on the edge of the frontier, a

paradoxical mixture of the Old South and the Wild West,

friendly to a fault but fiercely independent, God-fearing and

propped up by the Baptist beliefs in family and flag but hellraising, spiced with the edge of violence but naive and thoroughly unpretentious.

It was a place where neighbor loved helping neighbor, based

on a long-standing tradition that ranchers always left their

homes unlocked because you never knew who might need to

borrow something or cook a meal. But it was a place also based

on the principle that no one should ever be told what to do by

anyone, that the best government of all was no government at

all, which is why most citizens hated welfare, thought Michael

Dukakis, beyond having the irreversible character flaw of being

a Democrat, was the biggest damn fool ever to enter politics,

considered Lyndon Johnson an egocentric buffoon responsible

for the boondoggle of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and saw the

federal government's effort to integrate the Odessa schools in the fifties and sixties and seventies and eighties not as social

progress but as outrageous harassment.

At times Odessa had the feel of lingering sadness that many

isolated places have, a sense of the world orbiting around it at

dizzying speed while it stood stuck in time-350 miles from

Dallas to the east, 300 miles from El Paso to the west, 300 miles

from the rest of the world-still fixed in an era in which it was

inappropriate for high school girls to be smarter than their boyfriends, in which kids spent their Saturday nights making the

endless circles of the drag in their cars along the wide swathes

of Forty-second Street and Andrews Highway, in which teenage

honor was measured not by how much cocaine you snorted, but

by how much beer you drank.

But Odessa also evoked the kind of America that Ronald

Reagan always seemed to have in mind during his presidency,

a place still rooted in the sweet nostalgia of the fiftiesunsophisticated, basic, raw-a place where anybody could be

somebody, a place still clinging to all the tenets of the American

Dream, however wobbly they had become.

In the summer twilight, against the backdrop of the enormous sky where braids of orange and purple and red and blue

as delicately hued as a butterfly wing stretched into eternity,

young girls with ponytails and freckles went up and down

neighborhood streets on their roller skates. As the cool breeze

of night set in, neighboring families pulled up plastic lawn

chairs to conduct "chair committee" and casually meander over

the day's events without rancor or argument or constant one-

up►nanship. On other nights, parents gently roused their children from bed near the stroke of midnight so they could sit

together by the garage to watch a thunderstorm roll in from

Big Spring, gliding across the sky with its shimmering madness, those angular fingers of light cutting through the night

in a spectacle almost as exciting as a Permian High School foothall game.

There were many people in Odessa who, after the initial shock, had slowly fallen in love with the town. They found

something endearing about it, something tender; it was the

scorned mutt that no one else wanted. They had come to grips

with the numbing vacantness of the surroundings, broken only

by the black horses' heads of oil pumpjacks moving up and

down with maniacal monotony through heat and wind and dust

and economic ruin.

There were also those who had grown weary of it and the

oft-repeated phrase that what made it. special was the quality of

its people. "Odessa has an unspeakable ability to bullshit itself,"

said Warren Burnett, a loquacious, liberal-minded lawyer who

after roughly thirty years had Hed the place like a refugee for

the coastal waters near Houston. "Nothing could be sillier than

we got good people here. We got the same cross-section of assholes as anywhere."

There were those who found it insufferably racist and those

who didn't find it racist at all, but used the word nigger as effortlessly as one would sprinkle salt on a slab of rib eye and

worried about the Mexicans who seemed to be overtaking the

place. There were those who had been made rich by it, and

many more who had gone broke from it in recent times. But

they seemed gratified, as Mayor Don Carter, who was one of

those to go big-time belly up, put it, to have taken a "chance in

the free enterprise market."

There were a few who found its conservatism maddening

and dangerous and many more who found it the essence of

what America should be, an America built on strength and the

spirit of individualism, not an America built on handouts and

food stamps. There were those who found solace in the strong

doses of religion poured out every Wednesday evening and

Sunday morning by its sixty-two Baptist churches, nineteen

Church of Christ churches, twelve Assembly of God churches,

eleven Methodist churches, seven Catholic churches, and five

Pentecostal churches. And there were those like Burnett, who

saw religion in Odessa used not to reinforce religious beliefs at

all but as an excuse for people to come together and be made comfortable with their own social beliefs in racial and gender

bigotry.

Across the country there were thousands of places just like it,

places that were not only isolated but insulated, places that had

gone through the growing pains of America without anyone

paying attention, places that existed as islands unto themselves

with no link to the great cities except that they all sang the same

national anthem to the same flag at sporting events. They were

the kind of places that you saw from a plane on a clear night if

you happened to look out the window, a concentration of little

beaded dots breaking up the empty landscape with several

veins leading in and out, and then bleak emptiness once again.

It was a view that every traveler had seen a million times before, and maybe if you were a passenger on a plane bisecting

the night, you looked down and saw those lights and wondered

what it would be like to live in an Odessa, to inhabit one of those

infinitesimal dots, to be in a place that seemed so painfully far

away from everything, so completely out of the mainstream of

life. Perhaps you wondered what values people held on to in a

place like that, what they cared about. Or perhaps you went

back to your book, eager to get as far away as possible from

that yawning maw that seemed so unimaginable, so utterly

unimportant.

In the absence of a shimmering skyline, the Odessas of the

country had all found something similar in which to place their

faith. In Indiana, it was the plink-plink-plink of a ball on a parquet floor. In Minnesota, it was the swoosh of skates on the

ice. In Ohio and Pennsylvania and Alabama and Georgia and

Texas and dozens of other states, it was the weekly event simply

known as Friday Night.

From the twenties through the eighties, whatever else there

hadn't been in Odessa, there had always been high school

football.

In 1927, as story after story in the Odessa News heralded new

strikes in the oil field, the only non-oil-related activity that

made the front page was the exploits of the Odessa High Yel- lowjackets. In 1946, when the population of Ector County was

about thirty thousand, old Fly Field was routinely crammed

with thirteen thousand five hundred fans, many of whom saw

nothing odd about waiting in line all night to get tickets. Odessa

High won the state championship that year, which became one

of those events that was remembered in the psyche of the town

forever, as indelible as Neil Armstrong landing on the moon.

Where were you the moment the Bronchos won the championship? Everyone knew.

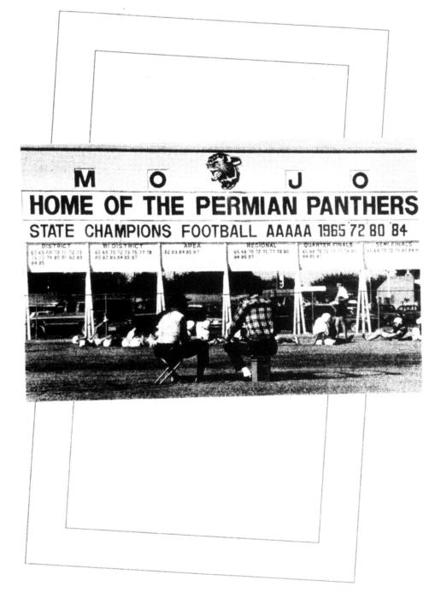

In the sixties and seventies and eighties, when the legacy of

high school football in Odessa transferred from Odessa High

to Permian High, instead of just waiting all night for tickets,

people sometimes waited two days. Gaines and the other Permian coaches were all too aware of the role that high school football occupied in Odessa, how it had become central to the

psyche of thousands who lived there. Expectations were high

every year and in 1988, if it was possible, they were even higher

than usual. The team had an incredible array of talent, the devout boosters whispered, the best of any Permian team in a decade. Winchell back at quarterback ... Miles back at fullback ...

Chavez back at tight end ... Brown back at flanker ... Hill back at

split end ... They listed off the names as if they were talking

about the star-studded cast of a movie spectacular, and they

frankly didn't see how Permian could miss a trip to State this

season.

They weren't the only ones to think so. The Associated Press,

making its predictions for the season, had picked Permian to

win it all. "Although Aldine, Sugar Land Willowridge, Hurst

Bell, San Antonio Clark, and Houston Yates are gaining big

support, the guess here [is] that there will be a big surprise

from out west," the article said. "Remember Odessa Permian?

The Panthers and their legendary `Mojo Magic' always contend

for the title."

To the boosters, that story was music to their ears, further

confirmation that when the middle of December rolled around

they would be on their way to Texas Stadium for the state championship. To Gaines, it only created more room for anger

and disappointment if the team didn't get there.

When he spoke to the players that very first time, he told

them to ignore the outside pressure that would inevitably swirl

around them during the thick of the season. "I'm gonna get

criticism and you're gonna get criticism," he said. "It don't mean

a hill of beans, because the only people that matter are in this

room. It doesn't make a difference, except for the people here."