Frigate Commander (37 page)

. . . blowing and raining with excessive hard squalls; the ship made a great deal of water, not a man in the ship had a dry hammock from the leaky state of the decks and upper works, and the labour at the pumps had become serious.

On the 20th, the

Melampus

anchored in Plymouth Sound, and Moore requested new orders. His belief was that he would be sent to Spithead for a major refit, and indeed this was the case, though with a slight twist. The

Melampus

was to carry 160,000 dollars in bullion taken from two Spanish galleons by the frigates

Naiad

,

Ethalion

and

Alcmene

. The government had purchased the bullion from the very happy captors and Moore had to deliver it to the Collector of Customs. His views on the success of his fellow frigate captains on this occasion were not recorded – but it would be surprising indeed if he were not both a little envious and bitter about his own hard luck. Reporting to the dockyard at Portsmouth, the

Melampus

was surveyed, and found to be in need of

‘. . . very considerable refit’

before she would be able to put to sea again. And Moore too needed a break. He obtained leave and set off to his parents’ new home, Marshgate House at Richmond.

12

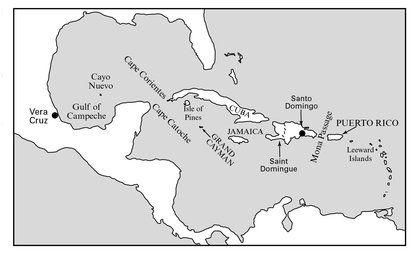

The West Indies (January 1800 – September 1801)

After a fortnight in London, Moore rejoined the

Melampus

and, at the early part of February, he was instructed to prepare the ship for foreign service. Within a few days he received orders to proceed to Cork to join a convoy bound for Jamaica and the Leeward Islands. Once there, he was to put himself under the orders of Admiral Sir Hyde Parker. Before leaving, he received a blow, when Lieutenant Martin was promoted to the rank of Commander and given the armed ship

Xenophon

. Moore applied for his Second, Lieutenant Busk, to be promoted in Martin’s place but the Admiralty had their own candidate, Lieutenant Edward Moore.

99

The new Lieutenant made a good first impression:

The Lieutenant whom they have appointed has conducted himself exceedingly well as yet and I hope will continue to do so. He seems to have much method and detail.

The

Melampus

left Cork with a convoy of eighty-four vessels. Accompanying them was Captain Lord Garlies in the frigate

Hussar

, which was to accompany them only as far as the North East Trades near Madeira. Moore was in two minds about his new station. He was not overjoyed about the prospect of Jamaica, with all the health problems which came with it, but on the other hand some of the station’s cruisers had been very successful over the previous six months. He had hopes, therefore, of some success himself,

. . . which . . . will probably render me tolerably easy for the rest of my life as to money matters. As to reputation I do not expect to acquire any on the Jamaica station for any thing but activity. Although the most brilliant

Coup de main

has been lately performed there of this or the preceding war, in the boarding and cutting out the

Hermione

from under the batteries of Porto Cavallo by Captain Edward Hamilton of the

Surprise

100

. I shall be very curious to learn the particulars of this heroic exploit from this gallant officer himself.

The passage was not without incident; on the night of 22 February, one of the more valuable ships, the

Clarendon

of Bristol, collided with the London vessel

Beaufoy

, striking her violently amidships. The

Clarendon

was badly damaged, as her stem was forced in considerably and her bowsprit broken off. When day broke, the

Beaufoy

had disappeared. Twice the frigates gave chase to vessels which they thought might be privateers, without catching them. Then on 27 February the weather deteriorated and the convoy began to scatter involuntarily. Moore struggled to gather them all together again into at least the semblance of a manageable group, but he was beginning to suffer the perennial stress of all convoy escorts;

We are retarded considerably by the inattention of the generality of the Convoy to our signals which occasions our frequently heaving to to collect them . . .

though

. . . a few of them, among which is a beautiful Greenock ship called the

Harmony

, are very correct and never out of their stations.

On the last day of the month they sighted Madeira and Garlies took his departure. Moore was sorry to see him go;

I felt a little at the

Hussar

leaving us, Lord Garlies has made up a good deal to me and I think him a very fine fellow. He knows his business well and is certainly very sharp and intelligent, he is an amiable fellow too, and a very agreeable companion.

101

His ship is in exceedingly good order and will always continue so while he commands her, he however does not give me the idea of a keen cruiser, but then we have had very little opportunity of judging.

As they headed off across the Atlantic, Moore found himself satisfied with the

Melampus

which was now in reasonably good condition, and Moore had her painted once again to help disguise her nature. However, some of the crew had deserted and the ship was no longer so well manned;

I can safely say that there are not 50 good seamen in the ship and about as many Ordinary seamen, the rest are not fit to be in a man of war’s top. I cannot account for the very great desertion that has constantly prevailed on board the

Melampus

whenever she has been in a place where there was much opportunity for it or temptation.

At least, for the present, the crew were all healthy and as they moved into the warmer latitudes he could only hope that they remained so;

Our men find a very great difference between this and the severe cold and wet they have been accustomed to; a Frock and trousers is now as much cloathes as a man wishes to wear, it is therefore a very easy matter for people to keep themselves clean and comfortable. If we can only keep clear of the cursed Fever, I am convinced our men will prefer the Jamaica station to Channel service.

There was, though, another change he noticed: as the days became warmer, a small number of the men complained of headaches, and some suffered spasms of some form or other. Moore too was beginning to suffer from the change in climate:

I am not sure that my practice of wearing a flannel waistcoat under my shirt may not exhaust me too much and some think that bathing so often as once a day debilitates, I hope not, it is such a luxury.

Reaching Barbados on 23 April, Moore detached the ships for that island pressing seven of their seamen. On 1 May the remainder entered Port Royal and he pressed another eight tolerably good hands. Having reported to the Commander-in- Chief, Moore had the opportunity to meet some of his fellow captains and catch up with news and gossip. He quickly realized that he was going to find the West Indies station difficult. His romantic tendencies encouraged him to believe that he was fighting in a just cause against an ignoble Republican tyranny. He was therefore shaken by his first real encounter with slavery in Jamaica, for the

‘. . . sight of so many mortals deprived of liberty has a gloomy effect on my mind’.

He was also perturbed to find that the ordinary rules of war, to which he had become accustomed on the European seaboard, no longer applied. His colleagues warned him that neutral vessels were not to be trusted and should all be treated as potential hostiles. Moore was used to adopting ruses to lure enemy shipping under his guns – but this was a practice with which he felt distinctly uncomfortable:

This is a business I am quite unexperienced in and do not at all like. Harsh measures are absolutely necessary to procure the real papers of the vessels, and this is vile and disgusting to people you are at peace with.

He may also have been a little taken aback by his visit to Admiral Hyde Parker, who

. . . lives in great comfort, and there is the appearance of expense to profusion, but the cruisers have realized to him a very ample fortune, and he seems inclined to enjoy it.

Moore was soon ordered to take the frigate

Juno

, Captain George Dundas commanding, under his command and sail to the Dry Tortugas to hunt for three Spanish frigates carrying treasure from Vera Cruz. The cruise started with a handicap, for Hyde Parker took off all of the

Melampus

’ Midshipmen leaving Moore short of men to put in charge of any prizes. Fever had also made its appearance on board. One of the stoutest members of the crew, the ship’s armourer, had been struck down and was now delirious. He was soon joined by one of the ship’s lads, struck down with a

‘putrid fever’

. The surgeon had little hope of the former recovering, though Moore was sceptical about the surgeon’s abilities:

I do not believe we have much medical skill on board; but this subject I do not at all understand. I believe for everything but the scurvy we are better here than in port.

On 10 May, the armourer, a handsome, strongly built Irishman, died;

He was always rather a favourite of mine. I used to go and talk to him very often and see that he wanted nothing but I never could cheer the fellow up, he was from being a daring licentious wild Irishman, become a poor chicken hearted creature. I am of opinion that the Irish, although brave and impetuous are much inferior in fortitude to the English and Scotch. They sink under adversity and are deficient in passive courage and firmness.

On 16 May, the

Melampus

and the

Juno

encountered an American ship which informed them that a Spanish convoy had recently sailed from Vera Cruz, but warned that it was heavily escorted. The two frigates set off once again to hunt for it, but Moore was having difficulty with navigation. Although he had a copy of Hamilton Moore’s

Practical Navigator

102

with him, he was unfamiliar with the West Indies and its currents, and his timekeeper was proving unreliable. Even so, they scored an early success, capturing a Spanish brig from New Orleans, which was loaded with case wood for making sugar crates. The vessel and her cargo were of only limited value, but Moore decided it was worth sending her in, and requested that Captain Dundas put a prize crew on board and send her back to Port Royal.

By now, two more of the

Melampus

’ crew were dangerously ill with fever and one of these died on the following day. He had been taken ill, complaining of dizziness whilst working in the top. Within a few hours he was delirious, and five days later he died. The seaman had complained constantly of dizziness and pains in his legs and thighs. The ship’s doctor had identified it as

‘putrid fever’

, and treated his ailment by purging, vomiting, and then keeping him on a diet of sago and bark. Moore observed this treatment with contempt, for he had little time for the medical man’s opinion, believing that he knew as much as the Doctor when it came to treatment. His friend Dr Currie had long been an advocate of cold baths as a treatment for the fever, and so Moore had applied this remedy to the other patient – to the obvious consternation of the rest of the crew;

I believe it had a very good effect on the other man who is ill and by no means out of danger, but the seamen stare at it.

Three days later the second seaman, a twenty-one-year old from Devon, died; and the Doctor himself was struck down with violent spasms. Fortunately, within a week he had recovered and the ship was free from fever. Even the sick lists were shorter than usual – though whether this was due to the threat of Moore’s personal remedy can only be guessed.

Moore liked what he had seen of Captain George Dundas

103

of the

Juno

. He was not a young man, in fact he was older than Moore, and had reached the rank of Post Captain late, in October 1795. He seems to have had little command experience until appointed to the

Juno

in September 1798. Nevertheless, Moore recorded in his journal,

I am well pleased with what I see of the

Juno

, she seems to me an active and effective ship, commanded by a shrewd and steady man.

The two frigates had now been several weeks out from Port Royal and the only enemy ship they had seen was the one they had taken. There had been plenty of neutral vessels, many of which might have been carrying enemy trade, but Moore had