From Baghdad To America (17 page)

Read From Baghdad To America Online

Authors: Lt. Col. USMC (ret.) Jay Kopelman

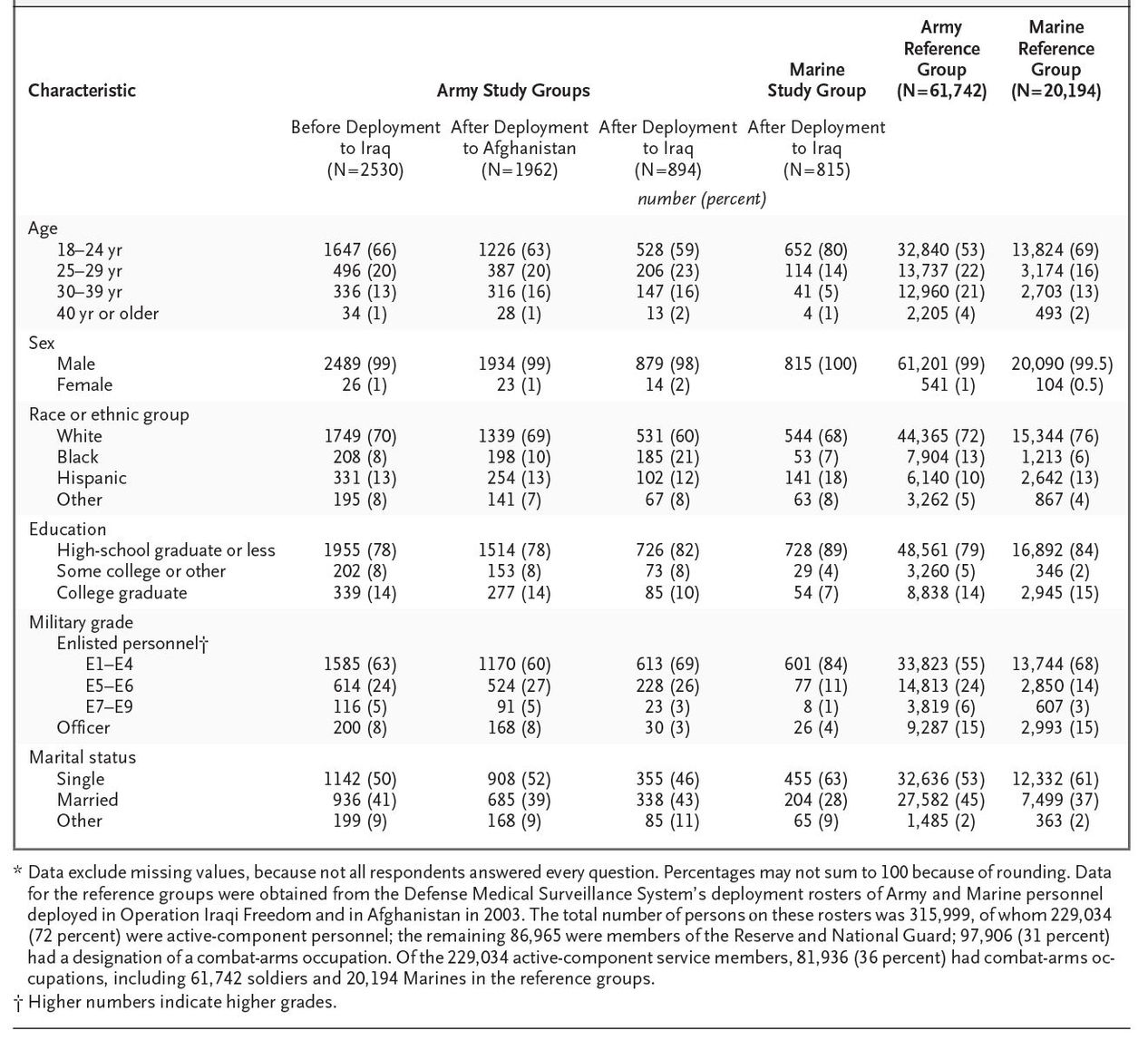

The demographic characteristics of participants from the three Army units were similar. The Marines in the study were somewhat younger than the soldiers in the study and less likely to be married. The demographic characteristics of all the participants in the survey samples were very similar to those of the general, deployed, active-duty infantry population, except that officers were undersampled, which resulted in slightly lower age and rank distributions (

Table 1

). Data for the reference populations were obtained from the Defense Medical Surveillance System with the use of available rosters of Army and Marine personnel deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan in 2003 (

Table 1

).

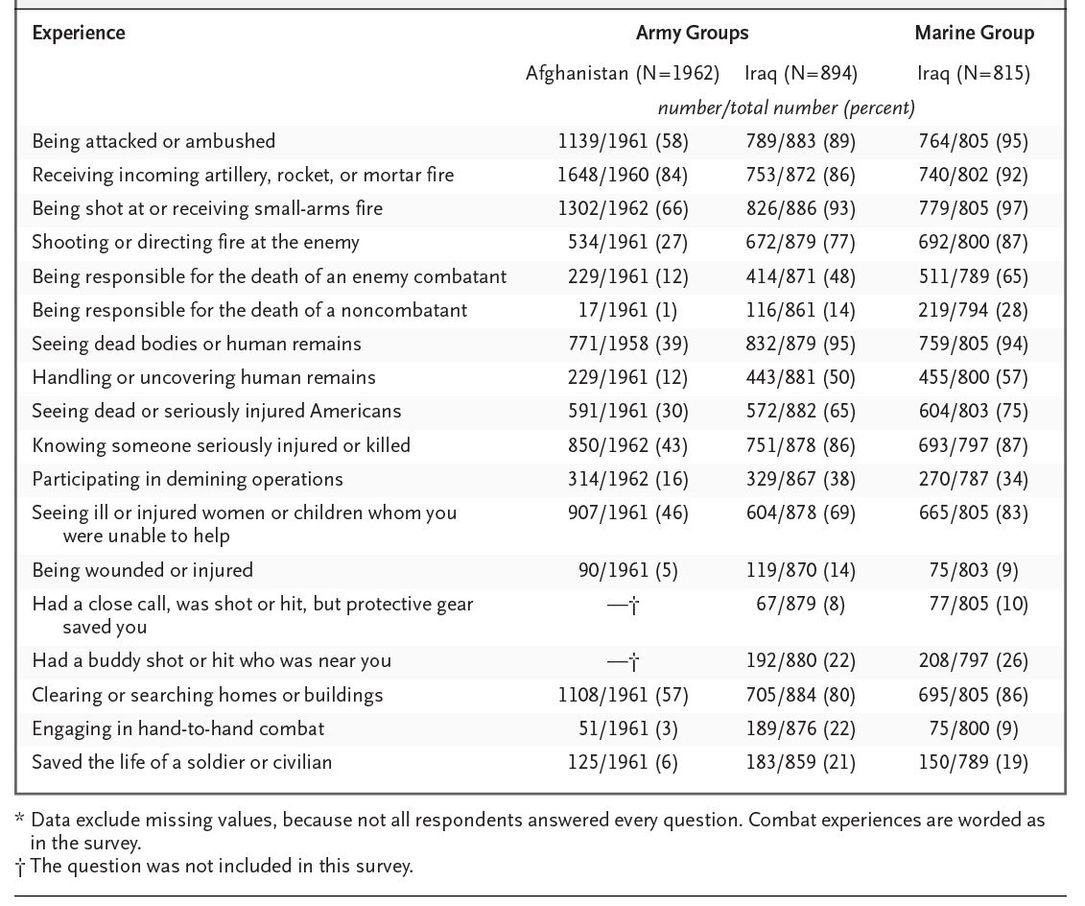

Among the 1709 soldiers and Marines who had returned from Iraq the reported rates of combat experiences and frequency of contact with the enemy were much higher than those reported by soldiers who had returned from Afghanistan (

Table 2

). Only 31 percent of soldiers deployed to Afghanistan reported having engaged in a firefight, as compared with 71 to 86 percent of soldiers and Marines who had been deployed to Iraq. Among those who had been in a firefight, the median number of firefights during deployment was 2 (interquartile range, 1 to 3) among those in Afghanistan, as compared with 5 (interquartile range, 2 to 13; P<0.001 by analysis of variance) among soldiers deployed to Iraq and 5 (interquartile range, 3 to 10; P<0.001 by analysis of variance) among Marines deployed to Iraq.

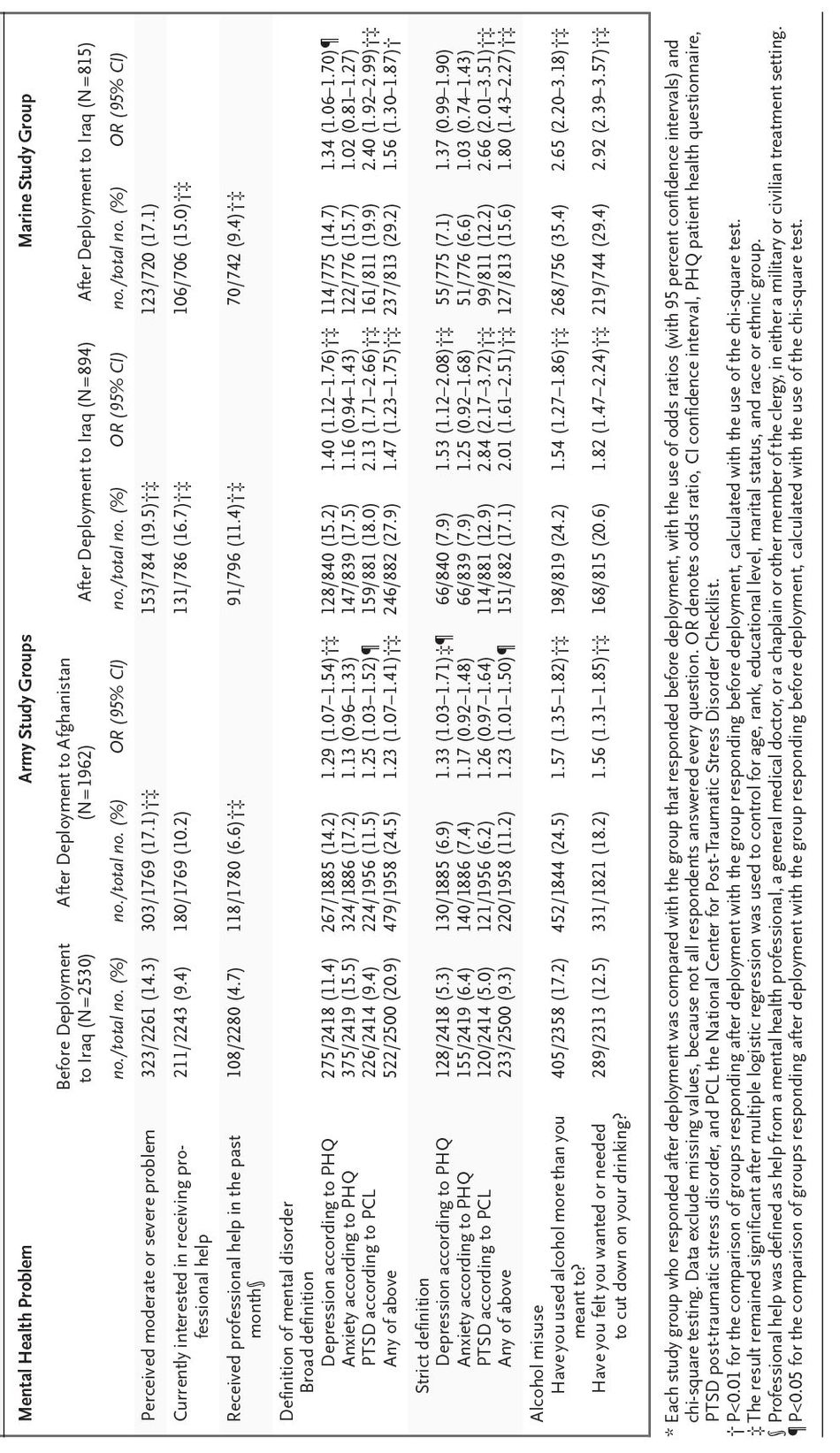

Soldiers and Marines who had returned from Iraq were significantly more likely to report that they were currently experiencing a mental health problem, to express interest in receiving help, and to use mental health services than were soldiers returning from Afghanistan or those surveyed before deployment (

Table 3

). Rates of PTSD were significantly higher after combat duty in Iraq than before deployment, with similar odds ratios for the Army and Marine samples (

Table 3

). Significant associations were observed for major depression and the misuse of alcohol. Most of these associations remained significant after control for demographic factors with the use of multiple logistic regression (

Table 3

). When the prevalence rates for any mental disorder were adjusted to match the distribution of officers and enlisted personnel in the reference populations, the result was less than a 10 percent decrease (range, 3.5 to 9.4 percent) in the rates shown in

Table 3

according to both the broad and the strict definitions (data not shown).

For all groups responding after deployment, there was a strong reported relation between combat experiences, such as being shot at, handling dead bodies, knowing someone who was killed, or killing enemy combatants, and the prevalence of PTSD. For example, among soldiers and Marines who had been deployed to Iraq, the prevalence of PTSD (according to the strict definition) increased in a linear manner with the number of firefights during deployment: 4.5 percent for no firefights, 9.3 percent for one to two firefights, 12.7 percent for three to five firefights, and 19.3 percent for more than five firefights (chi-square for linear trend, 49.44; P<0.001). Rates for those who had been deployed to Afghanistan were 4.5 percent, 8.2 percent, 8.3 percent, and 18.9 percent, respectively (chisquare for linear trend, 31.35; P<0.001). The percentage of participants who had been deployed to Iraq who reported being wounded or injured was 11.6 percent as compared with only 4.6 percent for those who had been deployed to Afghanistan. The rates of PTSD were significantly associated with having been wounded or injured (odds ratio for those deployed to Iraq, 3.27; 95 percent confidence interval, 2.28 to 4.67; odds ratio for those deployed to Afghanistan, 2.49; 95 percent confidence interval, 1.35 to 4.40).

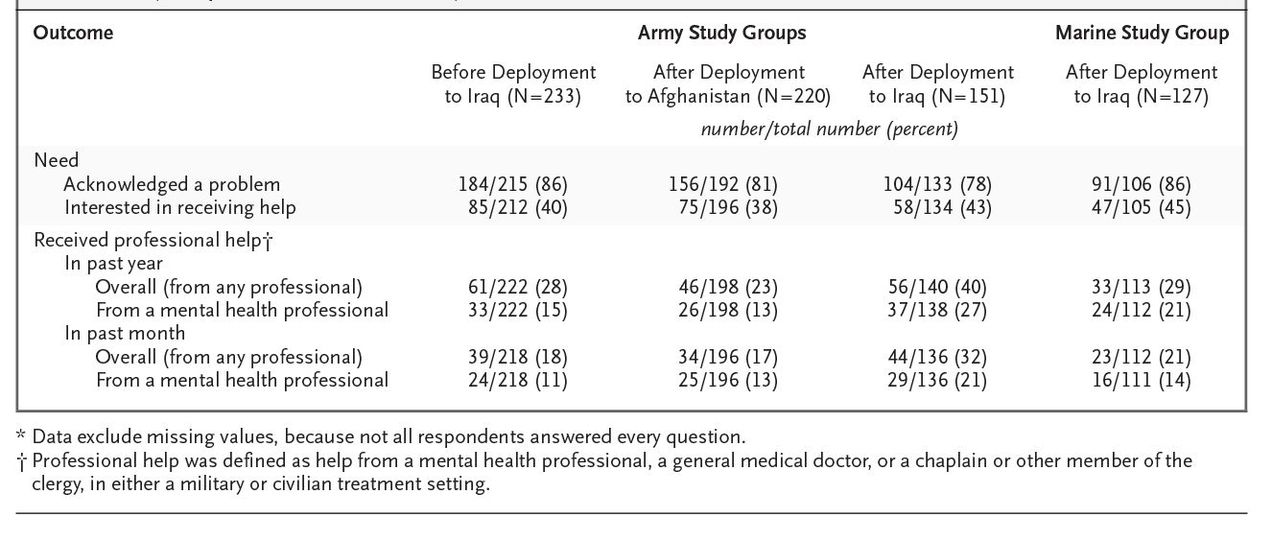

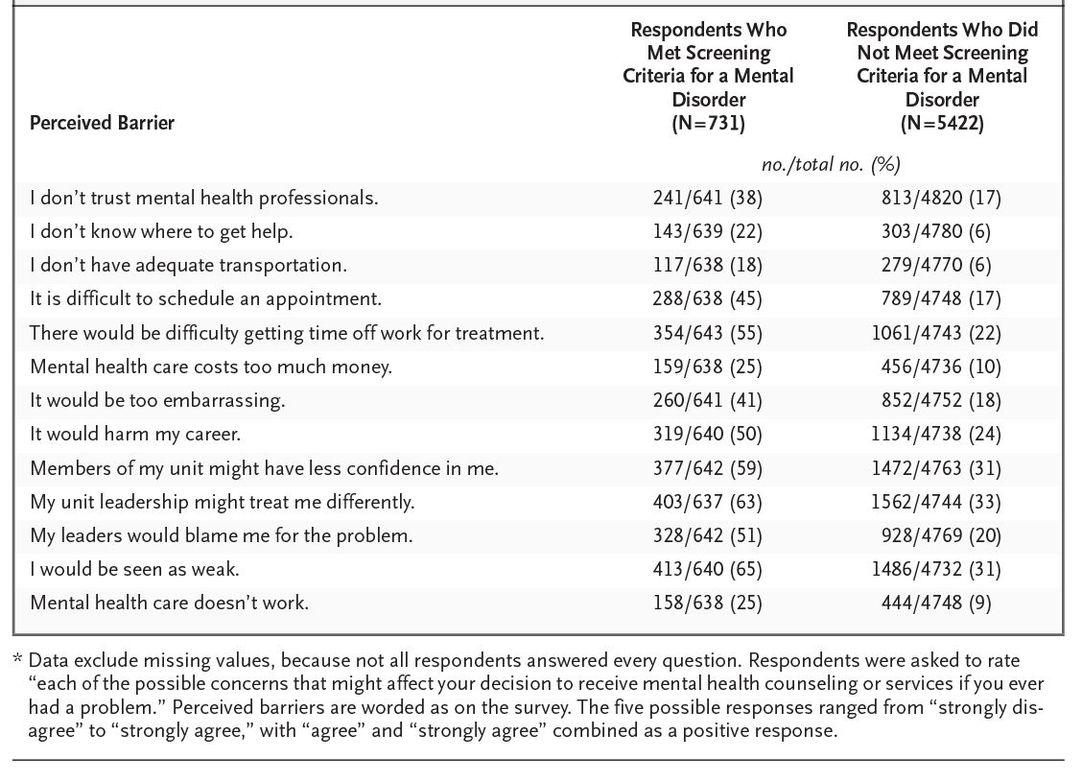

Of those whose responses met the screening criteria for a mental disorder according to the strict case definition, only 38 to 45 percent indicated an interest in receiving help, and only 23 to 40 percent reported having received professional help in the past year (

Table 4

). Those whose responses met these screening criteria were generally about two times as likely as those whose responses did not to report concern about being stigmatized and about other barriers to accessing and receiving mental health services (

Table 5

).

We investigated mental health outcomes among soldiers and Marines who had taken part in the ground-combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Respondents to our survey who had been deployed to Iraq reported a very high level of combat experiences, with more than 90 percent of them reporting being shot at and a high percentage reporting handling dead bodies, knowing someone who was injured or killed, or killing an enemy combatant (

Table 2

). Close calls, such as having been saved from being wounded by wearing body armor, were not infrequent. Soldiers who served in Afghanistan reported lower but still substantial rates of such experiences in combat.

Table 1

. Demographic Characteristics of Study Groups of Soldiers and Marines as Compared with Reference Groups.*

The percentage of study subjects whose responses met the screening criteria for major depression, PTSD, or alcohol misuse was significantly higher among soldiers after deployment than before deployment, particularly with regard to PTSD. The linear relationship between the prevalence of PTSD and the number of firefights in which a soldier had been engaged was remarkably similar among soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, suggesting that differences in the prevalence according to location were largely a function of the greater frequency and intensity of combat in Iraq. The association between injury and the prevalence of PTSD supports the results of previous studies.

25

These findings can be generalized to ground-combat units, which are estimated to represent about a quarter of all Army and Marine personnel participating in Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan (when members of the Reserve and the National Guard are included) and nearly 40 percent of all active-duty personnel (when Reservists and members of the National Guard are not included). The demographic characteristics of the subjects in our samples closely mirrored the demographic characteristics of this population. The somewhat lower proportion of officers had a minimal effect on the prevalence rates, and potential differences in demographic factors among the four study groups were controlled for in our analysis with the use of logistic regression.

Table 2

. Combat Experiences Reported by Members of the U.S. Army and Marine Corps after Deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan.*

One demonstration of the internal validity of our findings was the observation of similar prevalence rates for combat experiences and mental health outcomes among the subjects in the Army and the Marine Corps who had returned from deployment to Iraq, despite the different demographic characteristics of members of these units and their different levels of availability for recruitment into the study.

The cross-sectional design involving different units that was used in our study is not as strong as a longitudinal design. However, the comparability of the Army samples and the similarity in outcomes among subjects in the Army and Marine units surveyed after deployment to Iraq should generate confidence in the cross-sectional approach. Another limitation of our study is the potential selection bias resulting from the enrollment procedures, which were influenced by the practical realities that resulted from working with operational units. Although work schedules affected the availability of soldiers to take part in the survey, the effect is not likely to have biased our results. However, the selection procedures did not permit the enrollment of persons who had been severely wounded or those who may have been removed from the units for other reasons, such as misconduct. Thus, our estimates of the prevalence of mental disorders are conservative, reflecting the prevalence among working, nondisabled combat personnel. The period immediately before a long combat deployment may not be the best time at which to measure baseline levels of distress. The magnitude of the differences between the responses before and after deployment is particularly striking, given the likelihood that the group responding before deployment was already experiencing levels of stress that were higher than normal.

Table 3

. Perceived Mental Health Problems and Percentage of Subjects Who Met the Screening Criteria for Major Depression, Generalized Anxiety, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and Alcohol Misuse.*

Table 4

. Perceived Need for and Use of Mental Health Services among Soldiers and Marines Whose Survey Responses Met the Screening Criteria for Major Depression, Generalized Anxiety, or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.*

The survey instruments used to screen for mental disorders in this study have been validated primarily in the settings of primary care and in clinical populations. The results therefore do not represent definitive diagnoses of persons in nonclinical populations such as our military samples. However, requiring evidence of functional impairment or a high number of symptoms, as we did, according to the strict case definitions, increases the specificity and positive predictive value of the survey measures.

26

,

27

This conservative approach suggested that as many as 9 percent of soldiers may be at risk for mental disorders before combat deployment, and as many as 11 to 17 percent may be at risk for such disorders three to four months after their return from combat deployment.

Although there are few published studies of the rates of PTSD among military personnel soon after their return from combat duty, studies of veterans conducted years after their service ended have shown a prevalence of current PTSD of 15 percent among Vietnam veterans

28

and 2 to 10 percent among veterans of the first Gulf War.

4

,

8

Rates of PTSD among the general adult population in the United States are 3 to 4 percent,

26

which are not dissimilar to the baseline rate of 5 percent observed in the sample of soldiers responding to the survey before deployment. Research has shown that the majority of persons in whom PTSD develops meet the criteria for the diagnosis of this disorder within the first three months after the traumatic event.

29

In our study, administering the surveys three to four months after the subjects had returned from deployment and at least six months after the heaviest combat operations was probably optimal for investigating the long-term risk of mental health problems associated with combat. We are continuing to examine this risk in repeated cross-sectional and longitudinal assessments involving the same units.

Our findings indicate that a small percentage of soldiers and Marines whose responses met the screening criteria for a mental disorder reported that they had received help from any mental health professional, a finding that parallels the results of civilian studies.

30

,

31

,

32

In the military, there are unique factors that contribute to resistance to seeking such help, particularly concern about how a soldier will be perceived by peers and by the leadership. Concern about stigma was disproportionately greatest among those most in need of help from mental health services. Soldiers and Marines whose responses were scored as positive for a mental disor-der were twice as likely as those whose responses were scored as negative to show concern about being stigmatized and about other barriers to mental health care.

Table 5

. Perceived Barriers to Seeking Mental Health Services among All Study Participants (Soldiers and Marines).*

This finding has immediate public health implications. Efforts to address the problem of stigma and other barriers to seeking mental health care in the military should take into consideration outreach, education, and changes in the models of health care delivery, such as increases in the allocation of mental health services in primary care clinics and in the provision of confidential counseling by means of employee-assistance programs. Screening for major depression is becoming routine in military primary care settings,

12

but our study suggests that it should be expanded to include screening for PTSD. Many of these considerations are being addressed in new military programs.

33

Reducing the perception of stigma and the barriers to care among military personnel is a priority for research and a priority for the policymakers, clinicians, and leaders who are involved in providing care to those who have served in the armed forces. Supported by the Military Operational Medicine Research Program, U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, Ft. Detrick, Md.