Read From Baghdad To America Online

Authors: Lt. Col. USMC (ret.) Jay Kopelman

From Baghdad To America (4 page)

That experience jolted me alive again. And when I heard the good news, that Lava would live to run again, it struck me as clearly as if the heavens had opened and sent down a messenger cloaked in golden light: Lava embodied the most important lessons he'd taught me. That I still had the ability to love. That love would find me. That life matters.

Dear Colonel Kopelman,

I bought your book and raced home to dig up old memories. Memories from '53 - '54 Korea. There were friendly and loving dogs wandering around.

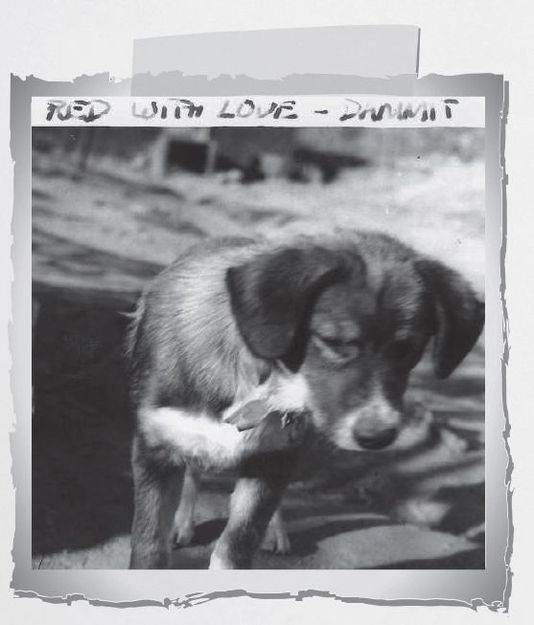

We had our share of war dogs: Donut (the eldest) was named for the roll of wire we used so much of. Dammit (middle) was named so we could get away with swearing at him without the chaplain being offended. T.L. (youngest) was named for a tool wiremen used.

After chow, we would go out with our tin plates and make sure the scrapings went to them.

Not one had a leash, and during the day, if we were busy, they went wandering around, some in dangerous spots. Some got in trouble with landmines.

There wasn't a hell of a lot to write about so I told my family about Dammit when I wrote home. My mother and my sister used to send packages to him. At Christmas, they'd be full of dog bonesâthere might have been a Hershey bar for me.

Dammit in a photograph sent to Corporal Roche, nicknamed “Red Dog” because he was a radio operator and a redhead

I had to leave the dogs behind when I was rotated home, but they had lots of admirers.

Roche with Donut

Thomas Roche

Corporal, First Marine Division

T.L

.,

the youngest pup

DESERT

-

COLORED GLASSES

“The days and weeks after you return from overseas duty will be a

transition

. During this time, service members often describe a range of emotions from excitement and relief, to stress, tension, or concern.... You may also feel distant, uninterested, or be overly critical and impatient with others. These types of behaviors and feelings are normal combat stress reactions.”

âNATIONAL CENTER FOR PTSD

One day shortly after I redeployed

(“came home,” in civilianspeak) in April 2005, probably right around the time Lava was hit by the Land Rover, it dawned on me that nothing was familiar anymore. The town I'd lived in for nearly twelve years, the people I'd hung out with, the woman I'd loved, all the things that I'd once known so well were . . . gone. There's no other way to describe it. You think that life at home stands still while you're in combat. That everyone sits around waiting for you and your fellow Marines to come back and pick up where you left off. Nope. Life goes on at homeâpeople go to the mall, they go to work, babies are born, relatives and friends die. The cycle of life continues, and sometimes you wonder what it's all for. All the fighting and death, when the folks back home just go about their business every day as though nothing's happened. As though the attacks of 9/11 never happened. Thanksgiving and Christmas come and go, you've missed another nephew's birth, you celebrate your own birthday in a foreign country without friends and family for what seems like the umpteenth consecutive year. How can people just take their freedoms for granted?

I hear people comment that we somehow “needed” 9/11, that it served as a wake-up call to our country. I just don't see how that's happened. A wake-up call for what? What actions have most Americans taken as even a sign of indignation with those responsible for 9/11? Have they stopped driving their gas-guzzling SUVs that are entirely dependent on Saudi oil? After all, it was the Saudisâstarting with Osama bin Ladenâwho were at the heart of the attacks that fateful Tuesday morning. But all that's happened here is finger pointing and accusatory debate. I know people are frightened, but they don't seem to do anything about itâexcept complain when they're delayed at the airport for security checks.

Driving home from the veterinary hospital, I searched in vain for landmarks. I'd been in the militaryâboth the Navy and the Marine Corpsâfor most of my adult life (for nearly twenty years at this point), and I'd made deployments and even been to Iraq previously at the outset of the war on terror in March 2003. But there was something different about this tour in this war and my return from it.

Lava had come to live with me, so to some degree I may have been seeing things through his eyes. To him, the posh yards of La Jolla, California, were as filled with danger and uncertainty as those fields of rubble in Fallujah. This is going to sound weird, but when he went ape-shit at the sound of the UPS truck lumbering down our street, or howled at the top of his lungs when someone, anyone, came to the door, or even when heâget thisâtook a piss on a nice couple's picnic blanket for no apparent reason ... I knew what he was feeling. I felt it, too. We were back; where exactly we'd arrived, however, wasn't clear.

If you asked me how I was doing, though, I would have said I was fine. A-okay. I'd done my job, I didn't regret a moment of it (still don't, by the way), and I was moving on. I'd served my country. I was even able to bring home my best friend. As my mother always says, “When Jay sets out to do something, he does it.” But she didn't believe me when I said I was fine. Better than fine. I didn't need to talk about the war, or what I'd seen. In fact, I was so tight-lipped about everything that my mother thought I surely must be working for the CIA. Lava had been there, and when he and I were together, we could just be, without thinking. No questioning glances, no narrowed eyes, no knowing nods.

Simply put, I just wanted to be alone with my dog. I wanted to see the happiness in his eyes when I took him running. He has a way of trotting with his head held high, tail curled over his body, and ears back, as if he's proud of me and of being with me ... but also 100 percent ready to tear apart anyone who doesn't agree that his owner is the coolest kick-ass guy in the park. I wanted to make him laugh by clowning around. You know, Charles Darwin observed that humans and animals have similar physical reactions to emotions. So when I laughed out loud at Lava, I know he was doing the same at me. (He could also be found trembling in fear and anger.) We played a mean game of tug-of-war, Lava growling and holding on until I inevitably gave up. The dog is relentless in his energy. To know Lava is to love himâor hate himâdepending on his mood and your thoughts about having your leg humped or foot gnawed. In either case, though, he inspires strong feelings.

Speaking of which, my feelings those first months back were pretty toxic.

I tried my best to blame other people for my anger. I was pissed, and I didn't hesitate to let everyone know it. They'd sat on their fat asses while I dodged bullets or skirted dead bodies on the streets. And now that I'd returned, they had the audacity to question my decision to bring Lava back with me. There were people who actually questioned my fitness as an officer and a Marine. No doubt they were the same assholes who sat around drinking cheap beer and watching reality TV. That's the stereotype, anyway. Ironically, the liberal wine-sipping antiwar types (viewers of

Fog of War,

rather than avid fans of

Cops

) were just as likely to misunderstand me and my actions. Maybe they couldn't comprehend that level of dedication or commitment to somethingâor someoneâbesides themselves.

After the

CBS Evening News

aired a piece about me and Lava, people with nothing better to do (why else would they bother?) sent comments to a CBS blog, some calling for my return to active duty so that I could go before a court-martial for my crime: violating a well-intentioned but ultimately misguided regulation. They said I was a disgrace to the corps and to the country. That hurt, particularly in light of Dick Cheney'sâand others'âVietnam deferments. Cheney was the biggest hawk in the administration, and no one questioned his authority. CBS has removed all the critical comments from its Web site, which I think is a shame. The insanity should be there for all to witness.

From a YouTube viewer (proves a point, I think): “u ppl need therapy for real . . . 100s of innocent ppl dying everyday in iraq and ur concerned about a fucking DOG??? ur a sick puppy whoever spent so much time on this in a war torn human rights disaster!!!”

I was also subject to some personal attacks in online book reviews. Not critiques of my book, but personal attacks. Several readers suggested that the entire story of finding and rescuing Lava was contrived. As in,

made up.

Check out this piece of brilliant literary analysis: “I came to conclusion that there was no dog, and dog kind of represents the concept of hope that after US departure from Iraq, Iraqi people can live in peace, and LT Colonel was a savior, and was trying to give hope to Iraqi people. It is kind of metaphor.” Genius, don't you think?

I've been accused of many things, such as spending six months playing with a dog in the sand. Tell me: How many of these critics were there when the smelly fuckers we were fighting were shooting at me and trying to blow me up? What?

I can't hear you!

That's what I thought.

We Marines don't whine about our job. It's the most important one that exists. We protect America. We protect the underdog. And above all, we protect one another. So when a well-dressed woman at a party looks at me pityingly, it's all I can do not to draw on my inner Jack Nicholsonâremember him as the Marine colonel in

A Few Good Men

?âand remind her that I do the protecting she and her friends are all afraid to do. That to me, honor and loyalty are more than just words, they are a way of life that I'm willing to risk with my own. I'm not alone in thisâall the way back to Odysseus, warriors have had to grapple with civilians who simply don't understand combat, who don't appreciate what's going on during the day-to-day existence of a soldier at war. Then we return and find we're expected to pretend that listening to our neighbor complain about our uncut lawn is actually worth a minute of time.

How does this square with the realization that I

am

back? I'm not shipping out again as I've done so many times. I'm here to stay, and taking a gander at some of the bad news showering down on us returning troops, I could definitely be in trouble.

I'd like to blame the entitled trainer at the gym, or the barista with attitude at Starbucks, but I probably also need to reconcile these facts in my mind: Soldiers and Marines returning from Iraq and Afghanistan are more likely than the average person to abuse alcohol and drugs, get divorced, and commit suicide. Military health care officials report seeing a spectrum of psychological issues, and a Pentagon task force gives the following statistics: Nearly half of returning National Guard members, 38 percent of soldiers, and 31 percent of Marines report mental health problems.

3

That's a lot of pain. Within the suicide data, one age group stands out: vets aged twenty through twenty-four who served in the “war on terror.” Their suicide rates are two to four times higher than found among civilians the same age.

4

Twenty-year-olds should not be committing suicideâthey should be going to college, meeting new girlfriends or boyfriends, and looking forward to the rest of their lives.

One really compelling fact jumps out from another Department of Defense screening. Combatants all fill out Pre- and Post-Deployment Health Assessments (PDHAs) when we deploy and when we come home. We're then supposed to complete another (the PDHRAâcan you guess?â“reassessment”) three to six months later. I included copies of these forms in the back of this book. Returning troops reported problems with interpersonal relationships four times more often between the first and second assessments in 2005.

5

You can add my name to the broken relationships board. I shouldn't be surprised, considering that in 2007 divorce among Army officers was up 78 percent from 2003, the year of the Iraq invasion, and more than 350 percent from 2000. The Army explains: “The stressors are extreme in the officer corps, especially when we're at war, and officers have an overwhelming responsibility to take care of their soldiers as well as the soldiers' families. There's a lot of responsibility on the leaders' shoulders, which, I can assure you, takes away from the home life.”

6

Label me Exhibit A, over here in the corner.

When I left for my second tour in Iraq in September 2004, my then girlfriend, whom I'll call Jane Doe, lived in one of the most affluent communities on the West Coast (not La Jolla, though). It wasn't the first time we'd been apart for an extended periodâI'd had a two-month deployment to Qatar at the end of 2003âbut it would be the first separation during which we knew there was a strong likelihood I'd see combat. As you can imagine, the stress of that aloneânot knowing whether I'd returnâcan signal the end of a relationship for many people. Jane and I managed to keep the dream alive throughout my tour, but it was the beginning of the end, as I can now see. Neither of us wanted me to go into combat with a breakup hanging over my head, and we certainly weren't going to acknowledge the possibility before I left.

It didn't take long for things to go very wrong when I got back. Maybeâokay, definitelyâI just wasn't ready to sign on with her for life, or maybeâagain, definitelyâI just didn't feel entirely comfortable in the relationship anymore. I was different. Not a different person, per se, but I'd definitely developed a different point of view about what's important in life. My priorities had changed. I think I'd be worried if they hadn't, after my experience. I'd never planned on being a gung-ho, tough-guy Marine out to kill. Nor did I have any altruistic dreams of saving the planet from one evil empire or another.