From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 B.C. to A.D. 68 (38 page)

Read From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 B.C. to A.D. 68 Online

Authors: H. H. Scullard

Tags: #Humanities

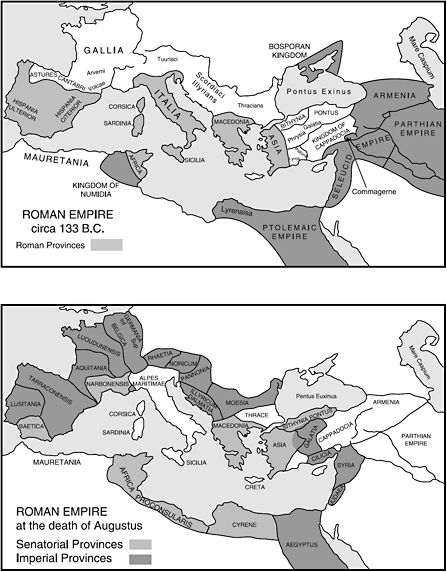

Many aspects of the ways in which Augustus improved upon the provincial administration of the Republic have already been noticed, but it will be well to draw some of them together here. The provinces fell into two groups, senatorial and imperial, which corresponded roughly with the ‘unarmed provinces’ and those in which legionary troops were stationed. The former were governed by proconsuls of consular or praetorian standing, the latter by ex-consuls or ex-praetors who bore the title of

legati Augusti pro praetore

or else by equestrian procurators. Though the proconsuls normally held their provinces only for a year, they were nevertheless very different from their Republican predecessors owing to the reorganization of the senatorial Order on a professional basis by Augustus. The senatorial and equestrian governors of the imperial provinces held office for longer periods. The employment of Equites in this way was a complete break with Republican traditions, especially in that such governorships were dissociated from the magistracy. It is true that equestrian officials in general were more concerned with the civil side of administration, but the procurators who governed provinces might command

auxilia

(while the equestrian Prefect of Egypt even commanded legions). Thus Augustus succeeded in building up an efficient body of salaried professional administrators: all of them indirectly depended on his favour, and a large proportion were directly appointed by him and responsible to him alone.

20

The provinces provided a very large proportion of the revenue of the Roman state, but even under the late Republic in normal conditions the provincials would perhaps not have found the burden of taxation unduly heavy or irksome, if its collection had been properly controlled: the system

was less open to criticism than the abuses to which it was too often subjected. Here was a field in which Augustus made one of his most valuable and enduring contributions. In order to secure a more equitable distribution of the burden he surveyed the resources of the Empire by means of censuses, which would clearly be easier to hold in the more urbanized provinces. Roman towns had to hold a census every five years which was conducted by local magistrates called

quinquennales

. It is not probable that a simultaneous census was taken of all the provinces, but gradually the resources of the whole Empire would be revealed. In Gaul, for instance, censuses are mentioned in 27 and 12 B.C., and again in A.D. 14 just after Augustus’ death, while the assessment by Quirinius of Judaea on its annexation in A.D. 6 is famous. Such surveys would provide information about the extent and ownership of land and about other forms of wealth: how detailed such information might be is shown by one of the edicts of Cyrene.

Such returns provided the basis for fair taxation. Direct taxes comprised

tributum soli

, levied on all occupiers of land, and

tributum capitis

, levied on other forms of property (not a poll-tax except in backward regions, as Egypt). All provincials, including Roman citizens and the

liberae civitates

, had to pay the land-tax, with the sole exception of the very few towns that enjoyed the

Ius Italicum

(i.e. the exemption enjoyed by Italy itself); those that had

immunitas

were perhaps exempt from the

tributum capitis

. Freedom from taxation could of course be granted to specific communities or individuals by Augustus. Indirect taxes included

portoria

(dues up to 5 per cent on goods that crossed certain frontiers; cf. p. 155);

21

the tax on manumission and on the sale of slaves (to which the Italians were liable; but only Roman citizens in the provinces paid death-duties,

vicesima hereditatum

: p. 188); grain for the governor and his staff (p. 155); and

aurum coronarium

, a gift paid later at the accession of an emperor. Revenue from provincial estates (e.g.

saltus

) that had become the emperor’s private property either by confiscation or bequest, was naturally paid into his

patrimonium

. Such estates would be managed by procurators, often freedmen; other imperial procurators were in charge of the mines, which they let out to contractors (

conductores

) to work.

22

‘Where the

publicani

are, there is no respect for public law and no freedom for the allies’, Livy had written of Republican times; it was by his control of these subordinates that Augustus rendered such valuable service to the provinces. In the imperial provinces the direct taxes were collected by an imperial procurator of equestrian status, who was largely independent of the governor: there might often be friction or enmity between the two men. The indirect taxes were still let out to contractors, but these

publicani

were carefully supervised. In the senatorial provinces the quaestor was responsible for finance, but

publicani

continued to act as middlemen in some of them; further, imperial procurators, who officially had authority only in connexion with

any of the emperor’s private property in a senatorial province, could keep an eye open for abuses. Unable immediately to dispense altogether with the help of

publicani

, Augustus subjected all financial operations to careful control and scrutiny.

Besides this immense boon of improved financial administration, the provinces gained many other solid advantages compared with Republican days, not least greater care in the choice and control of the governors, now salaried professionals whose prospects of promotion depended upon their efficiency. Naturally all misgovernment and corruption did not disappear: Valerius Messalla, proconsul of Asia, was alleged to have executed three hundred people on one day, and the exactions of the freedman Licinus, imperial financial procurator in Gaul, were notorious. But in general retribution was swifter and surer: imperial officials would be recalled and punished by the emperor; offenders in the senatorial provinces, possibly more numerous than in the imperial ones, were brought to trial before the Senate. Further, the improvement of communications made it easier for the emperor to keep in touch with and if necessary to restrain his officials: the road systems in the provinces were improved, and the imperial post, the

cursus publicus

(see p. 194), was extended to them. Though the local authorities who were responsible for the cost of this system might grumble, messages could be sent at an average speed of fifty miles a day in the imperial provinces. Governors could also be checked by means of the provincial Councils that grew up to promote the imperial cult (see p. 198). These assemblies of representatives from different parts of a province, meeting together annually, would naturally discuss their common interests as well as transact the business for which they had met. Since they lacked legislative powers, they could not develop into provincial parliaments, but they could voice any grievances and from the time of Tiberius they were authorized to approach the Princeps or Senate direct without the intervention of the governor, and to complain about, and even initiate the prosecution of, governors guilty of maladministration.

23

Augustus continued the Republican method of working through existing provincial communities, whether cities or tribes (p. 154).

24

Without an adequate basis of local self-government the administrative system that Rome imposed on the provinces would have collapsed: the officials had to rely on the co-operation of the provincials. Rome naturally encouraged city-life where there were communities with organized magistrates and senates. Where these did not exist (as in Gaul, and later in Britain), she used the tribal system, but before long the tribe (

civitas

) often borrowed the titles used in Roman cities and had its own

duoviri

and senate (the

ordo

). Rome did not enforce a policy of urbanization, but she encouraged it where she thought it feasible. Towns also served as centres to which large surrounding areas of territory were attached (‘attributed’) for administrative purposes; when these

became more civilized, municipal privileges might be extended to them. One of the chief ways in which city-life spread was the settlement of veterans in the provinces: to the forty or so colonies established in the triumviral period Augustus added at least a similar number: the majority were placed in peaceful areas in the west (as Narbonensis, Spain and Africa), but others were planted in the east (as those in Asia Minor, which ringed off the rebellious Homanades: p. 247).

25

The status of the cities in the provinces varied greatly, from colonies and

municipia

to ‘Latin’ cities and the great bulk of the ‘stipendiary’ cities. The most privileged were not, as under the Republic,

civitates foederatae

(though some of these survived), but those that had Roman citizenship, i.e. colonies and

municipia

. Before the time of Julius Caesar the idea of establishing Roman towns outside Italy was not popular, and Narbo was the only example: Roman citizenship was given to individuals in the provinces but not normally to cities. Caesar broke away from this narrow convention with his numerous overseas colonies for veterans and the poor, and Augustus, though less liberal in his ideas of the wisdom of widespread grants of franchise, followed Caesar’s colonizing policy. At the top of the hierarchy of cities stood the colonies: some of them were

immunes

and probably did not pay

tributum capitis

, and a few had the privilege of

Ius Italicum

which excused them from the land tax. Next came the

municipia

which were existing cities that had been given Roman citizenship, not settlements of immigrant Romans: thus Gades received the title and privileges from Caesar. In practice one chief difference between

municipia

and colonies was not that the magistracies in the former were less uniform, but that the prestige of the latter was higher; the

municipia

gradually (but more especially in the second century) began to seek the status and title of colony. They spread through the western provinces, especially in Mediterranean regions, but this status is not found in the east until much later. Below the

municipia

come the ‘Latin’ cities, which enjoyed a status partway between citizenship and non-citizenship, like the cities of Latium in relation to Rome in the earlier days of the Republic; the most important aspect was that their local magistrates became Roman citizens. These ‘Latin’ rights were usually given to cities before they were granted Roman citizenship and became

municipia

, and thus formed a valuable stepping-stone to greater reward. Lastly were the ‘stipendiary’ cities, which formed the majority in most provinces; a few of them had been ‘free’ or ‘federate’ cities under the Republic, but this status no longer exempted them from taxation, though perhaps they might expect less attention from the governor.

Thus Roman control in the provinces was to a large extent indirect and rested upon the support and loyalty of self-governing communities. The internal municipal constitutions of these cities naturally varied: those comprising Roman citizens, as colonies, would obviously tend to adopt a Roman

pattern, but even those that did not possess Roman rights tended to model their constitutions on that of Republican Rome, with popular assemblies, senates and magistrates, while the Greek cities of the East had enjoyed welldeveloped constitutions often for centuries. Local assemblies of burgesses elected local magistrates and accepted or rejected proposals put before them; gradually inhabitants of the

territorium

‘attributed’ to the town might receive limited voting rights. But influence tended to rest with the propertied classes who controlled the local senate (

ordo

or

decuriones

). This usually numbered one hundred; its members held office for life and consisted largely of ex-magistrates. The magistrates, as in Rome, were chosen on a collegial and annual basis: usually they consisted of

duoviri iure dicundo

, two aediles, and two quaestors. The

duoviri

exercised judicial powers, presided over meetings of the senate and assembly, were responsible for local Games and festivals, and every fifth year served as censors (

quinquennales

) when they filled up vacancies in the senate. As they received no salary and their office involved heavy expenses (gradually it became customary even to pay an ‘entrance fee’), the magistrates would naturally be drawn from the wealthier classes. Many men were extremely generous to their towns, and provided baths, theatres and other local amenities. The motive may often have been personal pride, but it was also often a genuine affection for their cities. Thus an active spirit of local patriotism fostered healthy municipal life, which was made possible by the degree of civic liberty that the Romans with wisdom and generosity accorded to the provinces.

An improved administrative system and the encouragement of local co-operation and responsibility were not by themselves enough. Their success depended in turn upon the maintenance of the greatest benefaction of Augustus to the Roman world, the

pax Romana

. His personal interest in the provinces, exemplified in his early tours of inspection, and his development of a consistent frontier policy to replace the somewhat haphazard development under the Republic, together with the creation of a standing army to hold the frontiers against barbarian attacks, helped to restore confidence and to open up for the provinces a prospect of increasing security and prosperity.

The long life of Augustus falls into three phases. The revolutionary faction leader, fighting his way to power, developed into a constructive statesman who with the help of loyal friends achieved a remarkable constitutional reform; then, stability won, he spent the last twenty or so years of his life in a period of quieter development that was, however, not unmarked by personal and national anxieties. Unlike his immediate successors, he turned not from better to worse but from worse to better: the youth, whom many

contemporaries may have branded as another ‘adulescentulus carnifex’, grew into a balanced and revered Pater Patriae. But behind all outward change the sources of his power continued unaltered. His personal character remains somewhat enigmatic. If he was superstitious, this did not deflect his judgement. Cautious and shrewd, in his private life he could be friendly and even homely, always preferring simplicity to luxury. Though he lacked the personal magnetism of Julius Caesar, he yet secured the enduring loyalty of his friends whose qualities supplemented some of his defects. The ruthlessness

of youth was replaced by an unshakable sense of duty and a determination to achieve what he believed to be in the interests of his country, despite many a setback and ill-health; proceeding by trial and error, he succeeded where a more doctrinaire approach would have led to disaster. He thus exemplifies the common-sense practical point of view of an Italian of the upper middle-class from the countryside from which his family stock derived. He may have lacked deep spiritual insight and have regarded the attainment of law and order as a higher ideal than the promotion of human liberties, and he clearly was not a man of genius in the sense that Julius Caesar had been, but his talents matched the desperate needs of his day. However Rome might develop in the future, her immediate need was peace without which there might be no future for the Roman world. That peace he secured, and with it he laid the foundations for the romanization of western Europe, which is his most enduring monument. His hope was not in vain: ‘Ita mihi salvam ac sospitem rem publicam sistere in sua sede liceat atque eius rei fructum percipere quem peto, ut optimi status auctor dicar et moriens ut feram mecum spem, mansura in vestigio suo fundamenta rei publicae quae iecero’ (Suetonius,

Augustus

, 28). ‘So may I be allowed to establish the State in a safe and secure position and gather from that act the fruit that I seek, that I may be called the author of the best government, and carry with me the hope, when I die, that the foundations which I have laid for the State will remain unmoved’.

26