Furious Love (44 page)

Authors: Sam Kashner

Elizabeth and Richard in

Divorce His Divorce Hers,

their first made-for-television movie and their last movie together. Like many of their films, it mirrored their private lives. November 1972. [Courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Press]

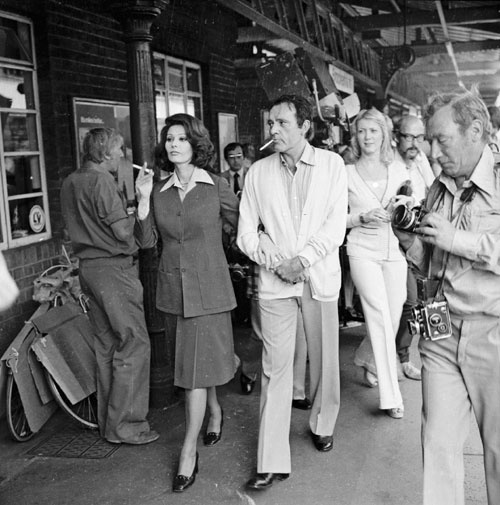

Richard with Sophia Loren, his co-star in the 1974 television remake of

Brief Encounter.

Elizabeth feared that Richard was “misbehaving” with the beautiful Italian film star. [Steve Wood/Express/Getty Images]

Headline news as Elizabeth and Richard announce their remarriage in August 1975. [John Frost Newspapers]

Elizabeth and Richard in Botswana, where they remarried on October 10, 1975. Their second marriage lasted less than ten months, ending on July 29, 1976. [Argus/A.P. Images]

After the couple's second divorce, Richard married former model Suzy Hunt in August of 1976. Suzy kept him sober, but she also kept him from his friends. They divorced five years later. [Popperfoto/Getty Images]

Elizabeth's marriage to U.S. Senator from Virginia John Warner lasted six years. She stayed in close touch with Burton by telephone throughout the marriage, her seventh.

Pictured here:

Warner, former U.S. President Gerald Ford, and Elizabeth. [John Full/UPI/Landov]

A brief encounter with Richard on Elizabeth's fiftieth birthday celebration, arriving at Legends nightclub in London on February 28, 1982. [© Alan Davidson]

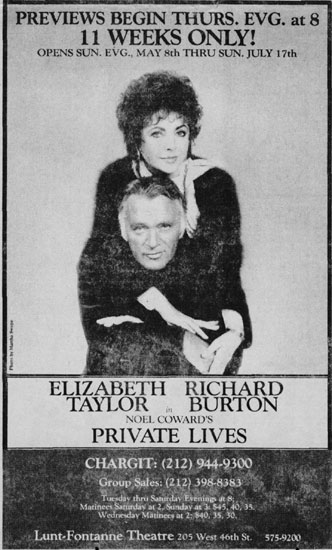

Elizabeth enticed Richard to co-star with her in Noel Coward's

Private Lives

in 1983, a financial success but a critical disaster. “Everyone bought tickets to watch high camp Liz and Dick,” Elizabeth said, “and we gave them what they wanted.” [John Frost Newspapers]

Richard married his young assistant, Sally Hay

(second from left)

, during the run of

Private Lives.

Elizabeth announced her engagement to lawyer Victor Luna

(far right)

, though the two would not marry. [© David McGough/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images]

The two women Richard most loved in his life: the sister who raised him, Cecilia “Cissy” James

(left)

and Elizabeth, attending Richard Burton's memorial service in August 1984. “And I'll love her till I die,” Richard wrote about Elizabeth. [Mirrorpix]

Elizabeth visiting Richard's grave in Geneva, Switzerland, on August 14, 1984, shielded by umbrellas from photographers camping at the gravesite. [Graham Wood/Daily Mail/Rex/BEImages]

Elizabeth and Richard leaving the theater in Montreal after a performance of

Hamlet

to attend their wedding reception, March 1965. [© Henry Grossman/from the Private Archives of Dame Elizabeth Taylor]

BLUEBEARD

“All my life, I think I have been secretly ashamed of being an actor⦔

âR

ICHARD

B

URTON

“No

Bluebeard

broads.”

âE

LIZABETH

T

AYLOR

T

he year 1971 brought the death of Elizabeth's most trusted friend and confidant, Dick Hanley. Hanley had managed her household affairs and had lovingly looked after her since she'd hired him away from Louis B. Mayer when she'd married Mike Todd. It was a terrible blow, following the death of her father two years earlier, especially as Hanley had been a father figure to Elizabeth. He was a bridge to her past, having worked as Mayer's executive secretary and knowing how the studio system worked, inside and out. Elizabeth was relieved that Hanley and Burton had accepted each other, though at times Burton playfully groused about being jealous of Elizabeth's affection for Dick Hanley.

In a favorite photograph of Elizabeth's, taken at a party after

Hamlet

's final performance in New York City, she is standing between two surrogate fathers, Philip Burton and Dick Hanley, as she beams at her then-eleven-year-old son Michael. In the photo, the two sixtyish,

bespectacled men bookend Elizabeth. She had lived to see the demise of the old studio system, and now, more recently, the ushering in of a new generation of filmmakers that threatened to put the Burtons out to pasture. With Hanley's death, her old world was gone. She was in uncharted territory.

After Hanley's funeral, everyone in the entourage moved up a notch. But without his wise overseeing of the Burtons' affairs, it was even more difficult for old, trusted friends to get through to them. They became more isolated. Neville Coghill, unable to get through, despaired reaching his former protégé and colleague: “The Burtons are protected by secretaries who themselves are protected by secretaries, and none of them answer lettersâ¦I understand now why many ancient emperors were guarded by deaf-mutes.”

Elizabeth had just begun filming

Zee and Co.

in London, so was unable to fly back to Los Angeles, but she spared no expense to pay for the funeral and an old-fashioned Irish wake, held at the Beverly Hills Hotel. She sent a magnificent display of flowers with a card that stated simply, “I will love you alwaysâElizabeth.”

Zee and Co.

(released as

X

,

Y

,

and Zee

in the States) was to be a fourteen-week shoot. Burton accompanied herâa mixed blessing, as Elizabeth found herself watching him like a hawk, especially jealous around Edna O'Brien, who posed a double threat to Elizabeth as she was (and is) a beautiful, redheaded Irishwoman as well as an acclaimed novelist. The movie is about a sexual triangle: Elizabeth plays Zee, a wife trying to keep her husband, played by Michael Caine, out of the arms of a young widow (the blond, waifish Susannah York). She does so by seducing the blonde.

Even when they weren't making a film together, their personal life continued to seep into their films, feeding the imaginations of filmmakers and screenwriters. In the movie, Caine plays a version of Richard Burton, and the screenplay made many allusions to the Burtons' marriage, such as their explosive, George-and-Martha rows.

Zee, Elizabeth's character, is raucous, loud, passionate, and, in Edna O'Brien's words, “a ruthless survivor.” Zee and her architect husband go at it hammer and tongs, verbally as well as physically, in graphic and explosive language. In fact, her character was described in the press as another Martha, complete with blowsy wigs and carrying unflattering extra weight (though in stills from the film, you can see that Elizabeth is far from fat; the public, perhaps, had never accepted her as anything but the slim, heartbreaking beauty of her youth, and every weight gain was noticed and commented upon. She was not allowed to age like an ordinary woman). Elizabeth continued to defend her domestic rows in the press. “We both let off steam by bawling at each other,” she told a writer from

Ladies' Home Journal

. “But it means

nothing.

And we both feel so much better for it. That's how it should beâ¦There's a difference between fighting and being mean.”

As usual, Elizabeth showed up at the studio with her entourage. According to Michael Caine, the cast and crew joked that if just the entourage bought tickets to see the movie, it would be a hit. “The people around her,” he said later, “make it seem as if you're working with the Statue of Liberty.” Her arrival was accompanied by much fanfare, as if the queen herself were deigning to visit the set. Prior to Elizabeth's appearance, messengers dashed in to announce her impending arrival. “She's left the hotelâ¦she's in the studioâ¦now she's in makeupâ¦she's out of makeupâ¦she's in hairâ¦she's out of hairâ¦she's getting dressedâ¦she's dressed and on her way!” When she finally arrived on the set, trailing her entourage, she bore a big pitcher of Bloody Marys, which she willingly shared with her costar, handing him a glass and toasting the beginning of the shoot. Nonetheless, Caine was impressed by her professionalism, remembering her as “the only actor I ever worked with who never ever flubbed a line.”

Caine was nervous about meeting “a living legend” for the first time, and equally nervous about meeting Richard Burton. He was

warned that Burton's presence on the set was his way of keeping an eye on Michael, considered to be a ladies' manâa real-life Alfieâat the time. But Burton, drinking heavily, usually spent the afternoons sleeping on the couch in Elizabeth's dressing room. The tremor in his hands that Weintraub noticed had worsened, and sometimes it was so bad he was afraid of embarrassing Elizabeth; on those days, he stayed away from the studio. A letter he wrote to Elizabeth on the back of a shooting schedule page for

Zee and Co.

read,

Dear Twit Twaddle etc.,

I have the shakes so badly that it would be fatal for me to come out to the studio. There is no power failure here so I am warm but still shaking. So come here tonight. I'm afraid that I had

one

drink but will drink no more until you come home. Try and make it early as we can then see the Cassius Clay fight togetherâ¦also I love you and long to see you but I don't want to shame you. I may even doâwith trembling handsâsome work. How about that?

He closes the letter with an admonition about her scenes with Michael Caine:

I love you and miss you and I think you to be the most desirable woman in the world and remember, NO KISSING WITH OPEN MOUTHS or breathless excitement and all that stuff. Otherwise, I will be down at the studio and certain girls will have a very rough time with certain husbands. I love you my little Twitch.âHusbs.

If Elizabeth was alarmed at Richard's tremors, she didn't show it. She herself continued to drink heavily, and they did not as yet consider Richard an “alcoholic.” Richard later confided to a friend, “She didn't exactly encourage me not to drink, but then she complained that I wouldn't stop drinking.” Elizabeth did have the insight to

know, however, that Richard drank because he constantly relived the wounds and grievances of his past, and he gave too much of himself to the public, in interviews and in his work. And Elizabeth had spent years “squelching [her] real feelings for fear they'd become public. All the years of covering up the pain and keeping it quiet had created a lot of scar tissue,” so she drank to free her emotions, just as Richard drank to numb his.

Despite their continued drinking, the Burtons embarked on a busy schedule of moviemaking, but none of the next four films they made together or separately would be distinguished, and none would make money. For Richard, there would be a handful of great performances ahead of him, and one more Oscar nomination. But not in the final three films that he and Elizabeth would make together.

Since

Cleopatra

, nothing had changed as much as the film business, and the financing for their next three movies would come from unlikely places. The year 1971 began with a labor of love, as Richard returned to Wales to film

Under Milk Wood

, Dylan Thomas's lyric “play for voices.” Burton's homage to his friend and countryman was produced by a small company, Timon/Altra Films International, and by his agent, Hugh French.

It was a small, artistic movie, but it had its advantages: it was filmed on location in the country of his birth. Whenever Burton felt his life was going off the tracks, he returned to Wales.

In January, Burton traveled alone to Wales to meet with the novelist and historian Andrew Sinclair, who had bought the rights to

Under Milk Wood

, the radio play that Burton had taken part in when it was first presented to the world in 1954. The film would be made for a low budgetâa mere £300,000âand Sinclair brought in Richard's old friend from his

Becket

days, Peter O'Toole, to play Captain Cat, a blind fisherman who is haunted by the voices of his drowned men. Burton would narrate as the play's First Voice, describing a day in the lives of several villagers in a small fishing town in WalesâLlareggub (which is “bugger all” read backward; a little inside joke that both Richard

and Elizabeth loved). Elizabeth was brought in for a small role, that of Rosie Probert, “the most glamorous hooker in the history of Welsh prostitution,” as one reviewer cheekily described her. As in

Dr. Faustus,

Elizabeth considered her role as nothing more than a cameo, so she didn't want star billing, but their names together still had magic, so both were listed above the title. The large cast was rounded out by Glynis Johns, Vivien Merchant, Sîan Phillips (married to O'Toole at the time), and Victor Spinetti, their Welsh friend (and Richard's fellow poet) from

The Taming of the Shrew.

Dylan Thomas was the poet that Richard had long wanted to be. Burton so identified with him that some people thought that Thomas had written the main narrative of

Under Milk Wood

with Richard's plangent voice in mind: “To begin at the beginning: it is a spring, moonless night in the small town, starless and Bible-black⦔ The film flushed out a secret that Richard had carried with him for the past eighteen years. He confessed to Sinclair that in the fall of 1953, Dylan Thomas had asked to borrow £200 from him, to avoid having to go to America to embark on a reading tour, reciting poetry for food and drink. Richard was an actor at the Old Vic at the time, and not rich, but he could have scared up the money. His refusal, he felt, was what forced the Welsh poet to go to America. It was on that trip that Thomas drank himself to death, downing eighteen straight shots of whiskey at the White Horse Tavern in New York City's Greenwich Village. Burton, as he tended to do, blamed himself.

However, being alone in Wales without Elizabeth and the entourage for those first few days was exactly what Burton needed. It was nourishment to him. His whole life he'd made sure he always wore a bit of red to commemorate the Welsh flag, and he never worked on March 1, St. David's Day (St. David being the patron saint of Wales). Visiting one of his sisters, he lounged in the bath with a glass of vodka in hand, looking out the window at laundry hanging on the line, and beyond that, the Welsh hills, where he could hear the calling of owls.

Burton was fond of telling a particular story about his father, Dic Jenkins, and now he thought of it. Jenkins used to sit outside the Miners Arms on Saturday evenings. “After he'd had a few jars,” Burton would explain, “he would fix his stupendously stoned eyes on his fellow miners and he would say in Welsh:

âPwy sy'n fel ni?'

And they would answer, â

Neb.'

“

âPwy sy'n fel fi?'

“

âNeb.'

”

Which translates to “Who is like us? Nobody. Who is like me? Nobody.” Elizabeth always liked that story, because the same could certainly have been said about herself and Richard. They were, and would always be, in a class by themselves.

Perhaps one reason Richard needed to return to Wales was to find some connection to his long-lost father, who had died when Richard was still married to Sybil, who now only existed for him in anecdotes, funny stories, and as the butt of jokes. Gianni Bozzacchi, still traveling with the Burtons as their in-house photographer, said that he “never heard Richard talk about his father” in any meaningful way. In Bozzacchi's opinion, Richard “did way too much for his brothers and sisters,” but seemed to repress all memory of the man who sired him. It was understandable, Bozzacchi thought. “First of all, his father was drunk all the time. He'd shake, even when he was sober. There must be something that made that transition to Burton, but it was always an untouchable subject. You'd never get anything out of him in that respect. Nothing. It's the cause of why Richard kept the anger inside,” Bozzacchi believes. “He had to suppress that. It was something that took an entire life.”

Filming the lyric play had been a pleasure for Burton, who took great delight in instructing Peter O'Toole exactly how to say the lines, and marveling at how true was Elizabeth's Welsh accent. Her rendering of Dylan Thomas's verse is immensely appealing, and it must have delighted Richard to see Elizabeth transformed into a “Welsh tart,” the subject of his erotic dreams since youth. But when the film was

released later that year, few people went to see it. Critics veered from describing it as lugubrious and longwinded, ill-suited to film, to praising Burton's fine and loving rendering of Dylan Thomas's verse. One of the reviewers who praised it was Judith Crist, who had not been generous toward the Burtons in the past. She wrote, “[T]he winning film of the moment is

Under Milk Wood

â¦[Burton's] voice washes over the screen.” Even Pauline Kaelâalso not a fanâdescribed in the

New Yorker

her enjoyment of “just sitting back and listeningâ¦you feel the affection of the cast and you share in it.” Though the movie, not surprisingly, made little money, Burton was glad he had undertaken it, paying his debt, as it were, to Dylan Thomas, to the poetry, and to the country that had made him who he was. And, perhaps, to his father.