Fusiliers (21 page)

Officers of a more down-to-earth and less Whiggish hue looked forward to the campaign ahead with greater enthusiasm. ‘We shall find the rebels enough to do at Philadelphia’, wrote William Dansey of the 1st Light Battalion, ‘and Burgoyne is playing the Devil with them to the northward.’ Howe himself apparently calculated that threatening the rebel capital would have the same effect that landing at New York had had one year before: it would force Washington to give battle.

For the 1st Battalion Light Infantry, action was joined in earnest on 3 September. When scouts detected Washington’s advanced guard taking post at Cooch’s bridge, it was quickly decided to attack them. There were about 800 enemy soldiers under the command of Major General Maxwell facing 400 Hessians and 1,000 British. General Howe appeared, ordering the Hessians to attack the bridge frontally. They were supported by the 2nd Light Infantry, while the 1st Battalion, containing the company of the 23rd Fusiliers among others, was ordered to move through thick woods to the left, cross the stream being defended by the Americans and attack them from behind.

The plan was pressed with great vigour, the jaegers skirmishing forward until they were near the bridge, and, being armed with rifles that lacked bayonets, drew their swords. The 1st Light Infantry meanwhile hacked its ways through the undergrowth for hours until it finally reached an impassable swamp. Attempts to surround the Americans were thus thwarted by the nature of the country and the enemy withdrew to fight another day. There was a good deal of disappointment in the 1st Light Infantry after this failure, but that just showed the battalion’s high morale and their keenness to hit the enemy. The opportunity came one week later at the Brandywine Creek.

At first light on 11 September the light infantry and grenadiers had already been marching for several hours. Two days before, the 1st Light Infantry had taken an American prisoner who confirmed that General Washington had taken post on a river a few dozen miles south of Philadelphia called the Brandywine. William Howe knew that if he was swift, he would catch the rebels and force them to fight a pitched battle. Having gathered intelligence about Washington’s position, he had soon detected a weakness, and on that day marched 8,000 men, just over half his army, to take advantage of it.

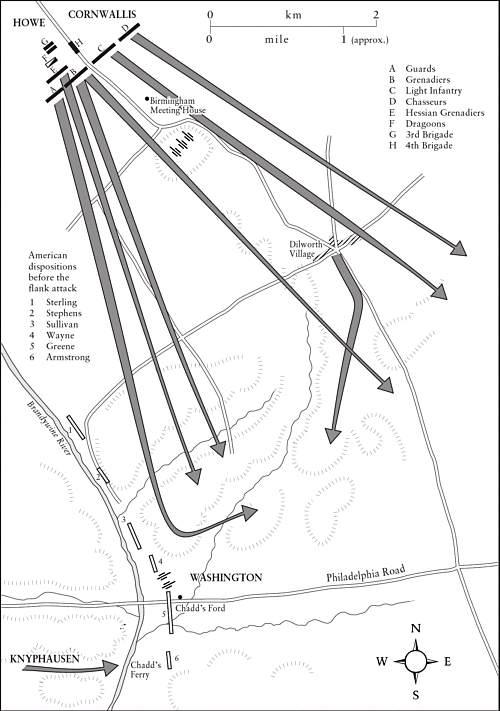

With Howe were Earl Cornwallis and the picked troops: flank battalions, Guards, Hessian grenadiers and a couple of brigades of British foot. The other arm of his battle, the division under Lieutenant General Knyphausen, would play a role similar to that performed by Grant and von Heister at Long Island, approaching Washington’s position frontally and pinning his forces close to three fords over the Brandywine. When Knyphausen heard the battle erupt to his front left, he would know that Cornwallis’s attack was going in, and it was time to force the river crossing. Knyphausen too had a couple of British

brigades under his command, one of them including the 23rd Fusiliers.

Brandywine, the British flank attack

In order to lead his troops in an arc around Washington’s right, Howe had to drive them a very long way, eighteen miles, so that his enemy would not see them coming. While they were marching around, Knyphausen’s advanced guard fell in with the Americans on his side of the river, and fought a series of smart skirmishes, driving them from fences and woods as he went. The American light troops were handled skilfully by General Maxwell, making the Hessian general pay for the hillside that would offer his artillery a commanding view of the river fords. In one place they laid a clever ambush for the Queen’s Rangers, a light corps raised in America. In another, the 23rd Fusiliers deployed into battle order during running exchanges of fire, taking one wood at the cost of several casualties.

Everything, though, depended on Cornwallis’s column. At 3 p.m. they reached Osborne’s Hill, the troops stopping hidden from view of the Americans as the rear part of the British column concertinaed. Some jaegers went to the top of the hill where they could see the American lines, with Howe and Cornwallis soon accompanying them, scanning the ridges in front with their telescopes. Even the Light Infantry out of view behind them could see columns of dust being kicked up from Washington’s army.

After underestimating the danger to his right for most of the day, and assuming Knyphausen to be the real threat, Washington had been firing off orders to redeploy his army. His line along the Brandywine Creek had to be bent back on its right, so as to construct a new deployment of troops at right angles to the original one.

While the redcoats gnawed on a chunk of meat or a lump of bread plucked from their haversacks, their generals watched the spectacle of their enemy deploying two divisions in their path, some of them just a few hundred yards to their front on Birmingham Hill. Howe was confident that all the sweat and dust being produced across the way were already futile.

The commander-in-chief walked back to a group of light infantry officers and beckoned to his orderlies to bring food. Sitting on the grass, savouring their picnic, the officers of Howe’s chosen corps were struck by his composure, one recording, ‘Everyone that remembers the anxious moments before an engagement may conceive how animating is the sight of the Commander-in-chief in whose looks nothing but serenity and confidence in his troops is painted.’

So sure was General Howe that things were going his way that he permitted his men a short rest. They were hot with hours of marching, the straps of their cartridge pouches and blankets wrapped around their bodies trapping heat and sweat in their clothes. Many swigged from canteens, knowing battle was imminent. The order to deploy came at 3 p.m. Columns of British troops began moving into the fields on the forward slope of Osborne’s Hill, with the companies moving ‘without hurry or confusion’, out from behind one another into battle order, side by side.

Captain Mecan and the 23rd Light Company were pretty much in the centre of the first line. Looking across his left shoulder he would have seen the 2nd Battalion of light infantry and dozens of green-coated Hessian jaegers trotting into their skirmish line ahead. To his front was a small road that led down the slope of Osborne’s Hill, across a stream and up towards a village called Birmingham, several hundred yards to the front. Just to the right of Birmingham was a distinct hill or knoll on which enemy cannon and troops could be seen. Over Mecan’s right, across the Birmingham road, were the 2nd Battalion of grenadiers, the 1st Battalion of grenadiers and then two battalions of guards. A second line of troops formed behind, the British 3rd Brigade behind Mecan and the other Light Bobs, the Hessian grenadiers, with their towering brass-plated caps behind their British counterparts. The last brigade of British was formed behind these two, in line with the Birmingham road, a

corps de réserve

should everything go wrong.

When the front battalions were all in line, Lieutenant Colonel William Meadows ordered his grenadiers, ‘Put on your caps!’ The precious bearskins that had been stowed safely during the morning’s long march were placed on the grenadiers’ heads as Meadows bellowed out, ‘For damned fighting and drinking, I’ll match you against the world!’

The bands struck up the grenadier’s march and the whole line began to tramp forward. With this stirring theme ringing in their ears, doubts about the purpose of the campaign were banished, officers and men succumbing instead to the intoxicating reverie of power. ‘Nothing could be more dreadfully pleasing than the line moving on to the attack,’ wrote one captain of the 2nd Grenadiers, who added, ‘Believe me I would not exchange those three minutes of rapture to avoid ten thousand times the danger.’

When the grenadiers reached the first American line on Birmingham Hill, there was a spluttering of American musketry, then the grenadiers rushed forward with the bayonet. Most of the defenders did not wait to get acquainted with those blades, running back.

On Mecan’s side of the road, things went quite differently. Some Virginia troops and artillery of Major General Adam Stephen’s division opened up with musketry and grapeshot. Several light infantry were scythed down in this hail of metal. Captain Mecan was among those hit. The battalion split in that moment of fear; some men rushed into cover behind a wall around the Birmingham Meeting House, others found themselves at the foot of Birmingham Hill, right under the guns. This group of light infantry, gripped by ‘the impatient courage of both officers and men’, ran up the hill just as the American gunners got their pieces limbered and away.

When the Light Bobs crested Birmingham Hill, they got a shock, for there, just a few score yards in front of them, were revealed new brigades of American troops, moving to the attack. The redcoats, wrote one light company officer, ‘had nothing to expect but slaughter’, but they pressed on.

Fortunately for the Light Bobs, the flight of the first line of Americans was disordering the new waves sent in by Major General John Sullivan as he struggled to regain control of his flank. Panic was spreading, even among the Marylanders who had shown great courage at Long Island. One of their officers described trying to force his way towards Birmingham Hill:

Of all the Maryland regiments only two ever had an opportunity for form, Gist’s and mine, and as soon as they began to fire, those [Americans] who were in our rear could not be prevented from firing also. In a few minutes we were attacked in front and flank and by our people in the rear. Our men ran off in confusion, and were very hard to be rallied.

The British grenadiers worked their way forward in the textbook style, allowing the enemy to fire, returning their own volley, and running in. Some estimated that they repeated this procedure five or six times as their enemies fell back from the line of one fence to another.

When the British got their own field guns on to the hill, they began spewing grapeshot back at the Americans and these showers of lead ripped lumps out of the draught animals pulling back some of General Stephen’s guns, cutting them down. Light infantrymen rushed forward

claiming five artillery pieces captured, a haul that would be rewarded by their general with a bounty of a hundred dollars per gun.

About one hour into this engagement, the American generals rallied their troops into a second distinct line, in the hope of allowing the soldiers who had been left opposite General Knyphausen to escape. That old German campaigner had however begun his own attack at around 4 p.m. when he heard the action becoming general.

The 4th and 5th Regiments went over first. Knyphausen moved them to Chadd’s Ferry, 300 yards to the right of Chadd’s Ford, the obvious crossing point on the Philadelphia road, in order to avoid some obstacles the Americans had placed there. Doing so, they also sidestepped the worst of the fire of several cannon covering the ford. British artillery had been firing rapidly from the height overlooking the river in order to ease the assault, but such an operation could be very tricky if the enemy put up a spirited defence, since men crossing a river packed together presented a tempting target. The 23rd waited its turn to cross behind them.

As the first British wave charged across the Creek, they were wading up to their stomachs through the stream, grapeshot smacking into bodies and water as they went. The defenders for the most part, however, were wisely reserving their fire until the British were right in front of them. The two advanced regiments splashed out of the creek, formed and moved forward. The redcoats were growing more tense with each step, knowing that the Americans to their front must let fly any moment with their saved volley. When the explosion of fire came, it ‘fortunately being directed too high, did but little execution’, the relieved serjeant major of the 5th wrote. The British response, though, did its job; the rippling wave of musketry broke the Americans and sent them running for the hills behind.

Advancing elements on Cornwallis’s right, the Guards and some of the grenadiers, could see the effects of Knyphausen’s attack as they pushed on. The two halves of General Howe’s vice were only a few dozen yards apart and, by 4.30, several of Washington’s brigades had already been broken by them. The 23rd, crossing Chadd’s Ferry without loss, moved up towards the Guards.

In the woods where Sullivan’s flank had formed its second line, there were still heavy exchanges of musketry to be heard, which caused some loss to the British brigade that had moved up through the grenadiers. By 5 p.m., though, the battle was effectively over.

Washington was able to extricate several more brigades in good order, to add to those that had run off in panic and might be rallied during the following days.

Of the human cost, estimates of the American casualties ranged from 400 to 1,200, exact figures being hard to reach due to the numbers that absconded from broken regiments. The British received 315 American deserters in the aftermath of the battle. Howe’s own losses had been 577 killed, wounded and missing. Major Andre, of the commander-in-chief’s staff, considered that ‘the Light Infantry met with the chief resistance’ on Birmingham Hill. The 1st Light Infantry had lost that day seven killed and 54 wounded. The casualties, among them Captain Thomas Mecan, were loaded on wagons to be taken to the port of Wilmington.