Fusiliers (35 page)

SEVENTEEN

In Which the 23rd Cover Themselves With Glory

The scene around the American bivouacs at Rugeley’s Mill on 13 August 1780 was one of nervous anticipation. Thousands of troops had marched into that South Carolinian township earlier in the day, scattering the Tory militia, who had kept up some outposts there. Serjeant Major William Seymour, of the Delaware Regiment, summed up the mood of Horatio Gates’s army as it anticipated its march on Camden: ‘Confident … that we should drive the enemy, we being far superior to them in numbers.’

At the core of Gates’s army was a division of 1,400 Continental troops, seven regiments from Maryland and one from Delaware. Their campaign had begun four months before at Morristown in Pennsylvania with orders to make haste for Charleston, in order to repel the British. They were seasoned regiments, quite the best division for such a task at General Washington’s disposal. It was the Marylanders and Delaware men who had faced the 23rd at Long Island in 1776, or been part of Sullivan’s division thrown back at Brandywine in 1777. Hard fighting and hard living had tempered them into something quite impressive. One British officer, a prisoner of the Americans in Pennsylvania, watched one of the Maryland brigades marching by shortly after it set off and recorded, ‘They were 450 strong, had good clothing, were well armed, and showed more of the military in their appearance than I had ever conceived American troops had yet obtained.’

Some of the journey down south had been done by ship, but most of it by foot-slogging through baking Virginia and North Carolina’s backcountry. Serjeant Major Seymour meticulously noted the marches

in his journal: 843 miles to Rugeley’s Mill. Towards the end, problems started.

As the Continental troops joined with Virginia men and thousands of militia from the Carolinas, food had run out. Gates blamed the local militia for ‘devouring’ the little fat of the land and admonished their commander, telling him, ‘This is a mode of conducting war I am a stranger to — the whole should support and sustain the whole, or the parts will soon go to decay.’ Gates sent off to Virginia, pleading for supplies, setting his sights also on the British magazines at Camden.

Cast in the role of pillagers of meagre Carolinian farms, the American soldiers returned hostile stares from the locals and convinced themselves there were loyalists everywhere. During the first two weeks of August the official ration had amounted to just half a pound of beef per man, ‘and that so miserable poor’, wrote the Delaware serjeant major, ‘that scarce any mortal could make use of it. Living chiefly on green apples and peaches which rendered our situation truly miserable, being in a weak and sickly condition and surrounded on all sides by our enemies the Tories.’

This bad atmosphere helped starve Gates of information as well as rations. Even early in August, his picture of British dispositions was hopelessly wrong, believing that Cornwallis had left the state and forces at Camden were being run down. Gates pushed on, anxious to do battle.

On the same evening that the Americans reached Rugeley’s Mill, Cornwallis had arrived in Camden, just eleven miles to the south. There the British had built a base with ample stores, protected by redoubts and a palisade of wooden stakes. The town had been established in 1733 as part of the early upland settlement and many of its citizens were hostile to the Crown forces. Even so, with 3,000 of them present, the locals exploited the opportunity to sell the product of their distillery and other supplies to the army.

When Cornwallis arrived it was the height of summer, a time considered by many as unsuitable for campaigning in those latitudes because of the epidemics it touched off. Some 800 of the troops at Camden were sick, stricken down by fluxes and fevers to which local people were often immune. In the township’s military hospital as well as many private houses, soldiers endured their personal hell, festering with fever and flux.

Among those who had fallen ill that August was none other than the 23rd’s major, Thomas Mecan. He had come through Lexington, Bunker Hill, Long Island, Brandywine and a dozen other affairs, but the forty-one-year-old Irishman, a tough customer, was finally faltering in his fight for life on that sweat-drenched bed. In the space of a couple of days Mecan burned up and died. One New York newspaper reported it thus: ‘We feel great concern in communicating the death of a brave veteran officer, Major Thomas Mecan, of the Royal Welch Fusiliers; a violent fever carried him off.’ Lieutenant Colonel Balfour, down in Charleston, wrote that Mecan’s ‘loss will be long felt and regretted in the regiment, his activity and exertions were too much for a bad constitution in this very unhealthy climate’.

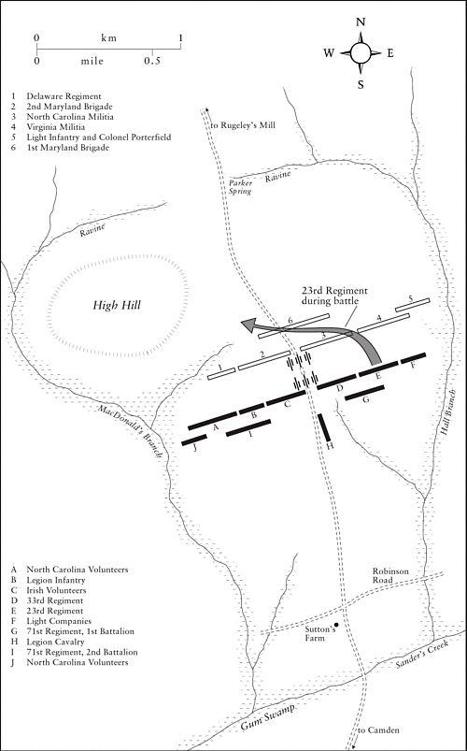

The battle of Camden

With Mecan’s death, only one of the older generation of officers remained. Frederick Mackenzie was last of the Minden leaders, but was far away in New York where, since the evacuation of Rhode Island, he had found his way on to General Clinton’s staff. The command of the 23rd in the field therefore went to a younger generation.

Cornwallis was loath to remove Balfour from that city, regarding his presence there as essential for the efficient administration of army and province. He could not, in any case, travel upcountry before the anticipated engagement. Control in the field of the Royal Welch thus devolved upon a twenty-five-year-old captain named Forbes Champagne. Irish-born of Huguenot descent, Champagne’s family was connected by marriage to an aristocrat who was willing to advance the young man’s career. Balfour, who knew Champagne well from the time they had both spent in the 4th Foot, would have preferred somebody else, but at that moment, on 15 August, news had not yet reached the lieutenant colonel in Charleston that his major and second in command had died.

On the eve of battle, the 23rd was able to parade thirteen serjeants, eight drummers and 261 rank and file. There were three captains and six subalterns. Those officers combined the physical vigour of youth with considerable battle experience. Champagne’s brother captains were both in their early twenties, but had served several campaigns.

Harry Calvert, still only sixteen years old, had acquired promotion to a lieutenancy and acting command of a company. Another lieutenant, Thomas Barretté, having none of Calvert’s family money to back him, was older, twenty-four, one of ten children (also of Irish-Huguenot origins); he had been in the forces since the age of fourteen,

when he joined the marines. For each of Calvert’s lucky turns of fate, Barretté might remember a disaster: his wife had died a few years earlier leaving him to maintain a son at school in England; resigning his commission in the marines for a captaincy in a loyalist regiment, he had been swindled by its colonel and left with no choice but to fight as a volunteer in the Guards light company in 1779, getting shot in the arm for his trouble. Barretté had exploited an old family connection to get recommended for a commission and considered himself deeply indebted to General Clinton for it. Sending money home for his son’s upkeep, Barretté was barely able to live on his pay.

What that Irish lieutenant, Calvert and the other subalterns had in common was their willingness to perform their duty in this scorching corner of America, to lead their men from the front. Several of these young Fusilier officers had strong religious feeling, and there were also a few loyalist Americans among them. So the 23rd’s cadre of officers serving in the field in their teens and twenties were fortified by strong beliefs. They were quite different from those disappointed middle-aged men who had celebrated St David around a festive board in Boston in March 1775, especially that dismal selection of them who had gone to such lengths to avoid serving in the field.

With such a shortage of officers, arrangements were reached that might have caused George III to splutter into his Bath water if he had ever found out about them. Intelligent young serjeants like Roger Lamb could play the part of officers, so when the 23rd marched out of Camden, he would be taking that honourable but dangerous post as Mecan had done at Minden, carrying one of the regiment’s two colours. The wise old head of Adjutant George Watson, in his early forties, was there to maintain discipline and administer the regiment.

Despite the sickness, the temperature and the loss of their major, the Welch Fusiliers were ready to take to the field with alacrity – morale was high. Credit for this belonged to two men outside the regiment, as well as all those active officers and serjeants within it. General Cornwallis, from the moment he arrived in Camden, infused the army with what Lieutenant Calvert called ‘that decision and promptitude which marks his military character’. The other vital character was James Webster, lieutenant colonel of Cornwallis’s own regiment, the 33rd, and commander of the brigade formed by uniting that corps with the 23rd.

Webster, the son of an influential Edinburgh theologian, an elder in the Church of Scotland, was a professional soldier of unstinting energy

and zeal for the service. Many officers had marvelled at Webster’s bravery in battle. His religious faith and occasionally maudlin personality left him apparently indifferent to death. After suffering the hardships of campaigning in Germany during the Seven Years War, Webster told his cousin, the diarist James Boswell, ‘Men are in that way rendered desperate; and I wished for an action, either to get out of the world altogether or to get a little rest after it.’ It can easily be imagined that Webster’s ‘wish for an action’ was just as great that 15 August in Camden.

Cornwallis had invested enormous energy and considerable sums of his own money turning the 33rd into an elite regiment. Years before it was sent to America, he had trained it in light infantry tactics of his own devising. The realisation of Cornwallis’s grand designs involved Webster as master builder. The Scotsman’s desire to gratify his patron was such that one captain of the 33rd noted bitterly, ‘[Webster] wishes to make his Lordship believe there is not an officer in the regiment but himself and that he is the only man of merit.’

In America during the campaigns of 1776 and 1777, Cornwallis had employed the 33rd as a full regiment of light infantry, taking them with his flank battalions on numerous operations. Even Henry Clinton had acknowledged admiringly this patronage in command, telling the earl, ‘Wherever you are I shall naturally expect to find them [the 33rd].’ Cornwallis, then, was the type of committed colonel that the 23rd lacked in William Howe, and Webster the excellent executive officer that circumstances had denied them for so long. Serjeant Roger Lamb had seen the 33rd serving in Ireland and noted a little enviously, ‘I never witnessed any regiment that excelled it in discipline and military appearance.’

It might be imagined that finding themselves thrown together with a model regiment such as the 33rd, under the eye of its impassioned leaders, the Welch Fusiliers might resent it, assuming that they would come second in all matters. This did not happen. Quite the contrary, for the spirit of emulation and competition possessed the Fusiliers and, as Serjeant Lamb wrote, ‘Both regiments were well united together, and furnished an example for cleanliness, martial spirit, and good behaviour.’ So well did they mix that the two understrength corps that formed Webster’s ‘brigade’ might have been assumed to be a single regiment of two wings or halves.

Webster’s brigade was guaranteed a key role, as the army prepared

to quit Camden, for its 530 troops were the principal redcoat force out of Cornwallis’s 2,000 or so troops. Two battalions of the 71st, Fraser’s Highlanders, were there too, but their total strength was less than that of the Welch Fusiliers. The British general would have no choice but to put loyalist American regiments into his battle line, namely the Royal North Carolina Regiment, as well as some North Carolina militia, corps made up mainly of Scottish refugees from that state, and the Volunteers of Ireland. As Cornwallis prepared for the fight, these American Tories were brigaded under Lord Rawdon, with Tarleton and his Legion ready to act as advanced guard or, once action was joined, the earl’s reserve. They set off on the evening of 15 August.