Galileo's Daughter (6 page)

Read Galileo's Daughter Online

Authors: Dava Sobel

Indeed, it appears that the Maker of the Stars himself, by clear arguments, admonished me to call these new planets by the illustrious name of Your Highness before all others. For as these stars, like the offspring worthy of Jupiter, never depart from his side except for the smallest distance, so who does not know the clemency, the gentleness of spirit, the agreeableness of manners, the splendor of the royal blood, the majesty in actions, and the breadth of authority and rule over others, all of which qualities find a domicile and exaltation for themselves in Your Highness? Who, I say, does not know that all these emanate from the most benign star of Jupiter, after God the source of all good? It was Jupiter, I say, who at Your Highnesses birth, having already passed through the murky vapors of the horizon, and occupying the mid-heaven and illuminating the eastern angle from his royal house, looked down upon Your most fortunate birth from that sublime throne and poured out all his splendor and grandeur into the most pure air, so that with its first breath Your tender little body and Your soul, already decorated by God with noble ornaments, could drink in this universal power and authority.

In the continuing paean of the remaining paragraphs of this dedicatory note, Galileo took it upon himself to name the planets the Cosmian stars. But Cosimo, the eldest of eight siblings, preferred the name Medicean stars—one apiece for him and each of his three brothers. Galileo naturally bowed to this wish, though he was thus forced to paste small pieces of paper with the necessary correction over the already printed first pages in most of the 550 copies of

The Starry Messenger.

The book created a furor. It sold out within a week of publication, so that Galileo secured only six of the thirty copies he had been promised by the printer, while news of its contents quickly spread worldwide.

Within hours after

The Starry Messenger

came off the press in Venice on March 12, 1610, the British ambassador there, Sir Henry Wotton, dispatched a copy home to King James I. “I send herewith unto His Majesty,” the ambassador wrote in his covering letter to the earl of Salisbury,

the strangest piece of news (as I may justly call it) that he hath ever yet received from any part of the world; which is the annexed book (come abroad this very day) of the Mathematical Professor at Padua, who by the help of an optical instrument (which both enlargeth and approximateth the object) invented first in Flanders, and bettered by himself, hath discovered four new planets rolling about the sphere of Jupiter, besides many other unknown fixed stars; likewise, the true cause of the

Via Lactea

[Milky Way], so long searched; and lastly, that the moon is not spherical, but endued with many prominences, and, which is of all the strangest, illuminated with the solar light by reflection from the body of the earth, as he seemeth to say. So as upon the whole subject he hath first overthrown all former astronomy—for we must have a new sphere to save the appearances—and next all astrology. For the virtue of these new planets must needs vary the judicial part, and why may there not yet be more? These things I have been bold thus to discourse unto your Lordship, whereof here all corners are full. And the author runneth a fortune to be either exceeding famous or exceeding ridiculous. By the next ship your Lordship shall receive from me one of the above instruments, as it is bettered by this man.

In Prague, the highly respected Johannes Kepler, imperial astronomer to Rudolf II, read the emperor’s copy of the book and leaped to judgment—despite the lack of a good telescope that could confirm Galileo’s findings. “I may perhaps seem rash in accepting your claims so readily with no support of my own experience,” Kepler wrote to Galileo. “But why should I not believe a most learned mathematician, whose very style attests the soundness of his judgment?”

The copy of

The Starry Messenger

that had the greatest impact on Galileo’s life, however, was the one he sent to Cosimo, along with his own superior telescope. The prince expressed his thanks late in the spring of 1610 by appointing Galileo “Chief Mathematician of the University of Pisa and Philosopher and Mathematician to the Grand Duke.” Galileo had specifically stipulated the addition of “Philosopher” to his title, giving himself greater prestige, but he insisted on maintaining “Mathematician” as well, for he intended to prove the importance of mathematics in natural philosophy.

In negotiating his Tuscan future, Galileo requested the same salary he had recently been promised by the University of Padua— the figure of one thousand to be paid now in Florentine

scudi

instead of Venetian florins. Rather than plead for more money, he made the base pay stretch farther by seeking official release from responsibility for his brother’s share of their sisters’ dowries.

Galileo also secured a bonus in personal liberty by arranging for his university appointment at Pisa to entail no noisome teaching duties. He would be free to study the world around him for the rest of his days, and to publish his discoveries for the benefit of the public under the protection of the grand duke, who promised to pay for the construction of new telescopes.

To have the truth

seen and recognized

Nine-year-old Livia rode south with her father when he moved to Florence to assume his new court post in September of 1610. They left behind the serpentine canals of Venice, where the doge’s palace brushed the water’s edge like a fantasy spun from pink sugar and meringue. They crossed the fertile Po Valley and the Apennine spine of the Italian peninsula into the foreign country where the grand duke reigned. Italy in the seventeenth century comprised a pastiche of separate kingdoms, duchies, republics, and papal states, united only by their common language, often at war with one another, and cut off from the rest of Europe by the Alps.

The landscape changed. Spires of cedar and cypress trees soared out of the rolling terrain, while ocher stucco houses sank roots into it. Here Galileo introduced Livia to the earth tones and square, sensible beauty of Tuscany. His older daughter, Virginia, already awaited them in Florence. She had gone the previous autumn at the insistence of Galileo’s mother, who took Virginia home with her after an unhappy visit to Padua. Finding her son too absorbed in his new spyglass to extend the sort of hospitality she demanded, and her not-quite daughter-in-law not worthy of her attention, Madonna Giulia cut short her intended stay and returned to Tuscany.

“The little girl is so happy here,” she crowed in a letter to Alessandro Piersanto, a servant in Galileo’s house, “that she will not hear that other place mentioned any more.”

Neither Virginia nor Livia had any idea when they would ever see their brother, Vincenzio, again. For the time being at least, Galileo deemed it best for the boy, still a toddler, to remain in Padua with Marina.

Soon after Galileo’s departure, Marina married Giovanni Bartoluzzi, a respectable citizen closer to her own social station. Galileo not only approved of their union but also helped Bartoluzzi find employment with a wealthy Paduan friend of his. Still, Galileo continued sending money to Marina for Vincenzio’s support, and Bartoluzzi, in turn, kept Galileo supplied with lens blanks for his telescopes, procured from the renowned glassworks on the Island of Murano, within the waterways of Venice, until Florence proved a source of even better clear glass.

Galileo rented a house in Florence “with a high terraced roof from which the whole sky is visible,” where he could make his astronomical observations and install his lens-grinding lathes. While waiting for the place to become available, he stayed several months with his mother and the two little girls in rooms he let from his sister Virginia and her husband, Benedetto Landucci. Galileo’s relatives provided an amicable enough atmosphere in their home, despite the recent legal fracas, but “the malignant winter air of the city” made him miserable.

“After the absence of so many years,” Galileo lamented, “I have experienced the very thin air of Florence as a cruel enemy of my head and the rest of my body. Colds, discharges of blood, and constipation have during the last three months reduced me to such a state of weakness, depression, and despondency that I have been practically confined to the house, or rather to my bed, but without the blessing of sleep or rest.”

He devoted what time his health allowed to the problem of Saturn, much farther away than Jupiter—at the apparent limit of his best telescope’s resolution—where he thought he could just discern two large, immobile moons. He described what he had seen in a Latin anagram, which, when correctly unscrambled, said, “I observed the highest planet to be triple-bodied.” Thus staking his claim to the new discovery without making a fool of himself before establishing proper confirmation, he dispatched the anagram to several well-known astronomers. None of them correctly decoded it, however. The great Kepler in Prague, who by this point had held the telescope and deemed it “more precious than any scepter,” misinterpreted the message to mean Galileo had discovered two moons at Mars.

*

All through that same autumn of 1610, with Venus visible in the evening sky, Galileo studied the planet’s changing size and shape. He kept a telescope trained on Jupiter, too, in a protracted struggle to ascertain the precise orbital periods of the four new satellites to further validate their reality. Meanwhile, other astronomers complained of struggling just to catch sight of the Jovian satellites through inferior instruments, and therefore they questioned the bodies’ very existence. Despite Kepler’s endorsement, some sniped that the moons must be optical illusions, suspiciously introduced into the sky by Galileo’s lenses.

Now that the moons had become matters of the Florentine state, this situation required immediate remedy to protect the honor of the grand duke. Galileo scrambled to build as many telescopes as he could for export to France, Spain, England, Poland, Austria, as well as for princes all around Italy. “In order to maintain and increase the renown of these discoveries,” he reasoned, “it appears to me necessary . . . to have the truth seen and recognized, by means of the effect itself, by as many people as possible.”

Famous philosophers, including some of Galileo’s former colleagues at Pisa, refused to look through any telescope at the purported new contents of Aristotle’s immutable cosmos. Galileo deflected their slurs with humor: Learning of the death of one such opponent in December 1610, he wished aloud that the professor, having ignored the Medicean stars during his time on Earth, might now encounter them en route to Heaven.

To cement the primacy of his claims, Galileo thought it politic to visit Rome and publicize his discoveries around the Eternal City. He had traveled there once before, in 1587, to discuss geometry with the preeminent Jesuit mathematician Christoph Clavius, who had written influential commentaries on astronomy, and who now would surely welcome news of Galileo’s recent work. Grand Duke Cosimo condoned the trip. He thought it might heighten his own stature in Rome, where his brother Carlo currently filled the traditional position of resident Medici cardinal.

Unfortunately, Galileo’s sickly reaction to the air of Florence prevented him from setting out until March 23, 1611. He spent six days on the road in the grand duke’s litter, and at night he set up his telescope in every stop along the way—San Casciano, Siena, San Quirico, Acquapendente, Viterbo, Alonterosi—to continue tracking the revolutions of Jupiter’s moons.

Upon Galileo’s arrival at week’s end, the warmth of his Roman welcome surprised him. “I have been received and feted by many illustrious cardinals, prelates, and princes of this city,” he reported, “who wanted to see the things I have observed and were much pleased, as I was too on my part in viewing the marvels of their statuary, paintings, frescoed rooms, palaces, gardens, etc.”

Galileo garnered the powerful endorsement of the Collegio Romano, the central institution of the Jesuit educational network, where Father Clavius, now well into his seventies, was chief mathematician. Clavius and his revered colleagues, regarded by the Church as the top astronomical authorities, had obtained telescopes of their own, and now as a group corroborated all of Galileo’s observations. Bound as these Jesuits were to Aristotelian belief in an unchanging cosmos, they did not deny the evidence of their senses. They even honored Galileo with a rare invitation to visit.

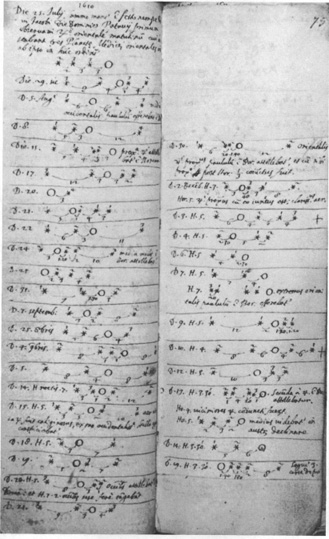

Page from Galileo’s notebook tracking the orbits of the satellites of Jupiter