Gallipoli (25 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

The hungry maw of the Dardanelles appears before Admiral de Robeck and the fleet, a maw that has swallowed whole tens of thousands of fighting men before them and never even bothered to spit out the bones. Yes, this is it, the entrance to the channel, a relatively narrow 4400 yards from east to west. It will be here that the first of the Turks' defences may now lash out at them.

Once through the mouth of the Straits, the fleet must continue to shrug off the cannons in the flanking forts and, more significantly, survive the fire of the many mobile howitzers the enemy has set up along both shores (under the watchful eye of their German comrades). About five miles in, the surviving battleships will reach the widest part of the Dardanelles â four and a half miles from shore to shore and just enough width for the ships to turn around â which continues for some three and a half miles before narrowing again. Fourteen miles from the entrance, the fort town of Kilid Bahr is reached on the western shore and Chanak on the eastern shore, and the âNarrows', in their true sense, begin â just 1600 yards across at the thinnest point and continuous for five miles.

Beyond that, the Narrows widen again to a distance of four miles, until the town of Gallipoli on the western shore marks the beginning of the Sea of Marmara. If the ships can just reach that point, they can go all the way to Constantinople, 200 or so miles to the north-east. (True, it is expected that

Goeben

,

Breslau

and the rest of the small Turkish Navy will be waiting for them in the Sea of Marmara, but ideally the British ships will arrive in sufficient numbers to simply overwhelm the lot of them.)

Of course, it is the Narrows that is the true obstacle, and most particularly the five lines of mines that the British know lie across it.

Leading the way,

Agamemnon

enters the mouth of the Dardanelles, flanked by

Prince George

and

Triumph

, even as the destroyers and minesweepers soon move forward to clear any mines that might lie in their way.

Queen Elizabeth

follows them all, sticking close to the European shore.

Once Admiral de Robeck has his Line A battleships correctly positioned, he orders the hoisting of the signal flag âCarry on' at 8.15 am.

Let the hostilities commence.

Among the gun crews beneath the turrets, each Lieutenant flicks the switch. A low buzz fills the air, indicating the circuit is now alive. All is tense and so quiet that they can hear the waves slapping against the side of the ship ⦠until the calm is shattered by two rings on the fire gong ⦠âStand by!'

Then another ring ⦠âFire!'

âThe air in the gunhouse, suddenly compressed then released by the great mass of the gun, was rent at the same time by the noise of the explosion. Before the reverberations had died away the gun's crew, with febrile activity, were reloading.'

15

As are the Turkish artillery and howitzer crews lining both sides of the Dardanelles. With the infidels now in view, the bugleman blows his horn and all the companies engage in a finely focused frenzy of activity. Some bring shells, others open the breeches and calculate the ranges, while still more strain at pulleys to put the charges into place. Everywhere the men's faces are lit up with the special fervour reserved for those engaged in nothing less than a holy war. Above the shouted commands and the sounds of the shells being rammed into breeches and the breechblocks slamming shut, all that can be heard is the sing-song chant of the leader, intoning the same prayer Muslims have used before battle for all of the last 13 centuries: â

Allah is great, there is but one God. And Mohammed is his Prophet!

'

16

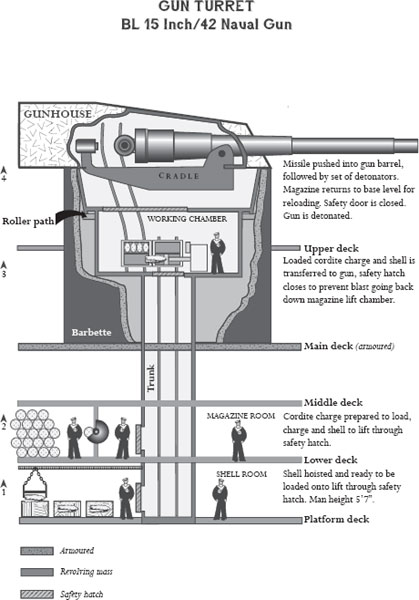

Gun turret, by Jane Macaulay

There!

Just after 11 am, puffs of smoke are spotted coming from the back of the fort at Kum Kale on the Asian side of the Dardanelles entrance, to be shortly followed by a rolling boom and ⦠spouts of water appear some 500 yards in front of the first ships.

To the fore, in the first wave of attack, Line A, is

Queen Elizabeth

â bearing the flag of Admiral de Robeck â together with

Agamemnon

,

Lord Nelson

and

Inflexible.

In the next wave, Line B, just over a mile behind, is the French squadron, comprising

Gaulois

,

Charlemagne

,

Bouvet

and

Suffren

, with the British battleships

Prince George

on the port side and

Triumph

to starboard, riding shotgun. (

Majestic

and

Swiftsure

are to relieve these two covering ships in due course.)

Biding their time before they enter the fray, waiting just outside the Straits, are the ships making up Line C â

Vengeance

,

Irresistible

,

Albion

and

Ocean

â which will relieve the ships in Line B.

Canopus

and

Cornwallis

are held back in reserve.

With the fleet now into the Straits proper, it is the Turkish mobile batteries that do most of the spasmodic firing, and though some of the shells find their mark, the howitzers are too far away to actually bring concentrated fire to bear on the invading naval force. They are like boxers circling in a ring, throwing wild haymakers at arm's length.

But now, the field guns and mobile howitzers of the Intermediate Defences unleash a few glancing blows on the leading line of British ships, even as those ships launch their own salvos upon the forts at the Narrows.

Just before noon, Captain Hilmi stands at the head of his command post at Rumeli Mecidiye Fort, thinking hard. Though the enemy ships are not quite within reach of his guns â and his orders remain not to fire until they are â there is no doubt that his fort is within

their

range. Several shells have already knocked out some of his guns and killed several of his brave men.

They must at least try to strike back.

â

AteÅ! â Fire!

' he yells to his battery officer.

â

AteÅ!

' comes the reply through the megaphone, down the line, to the surviving soldiers manning the guns.

Just as they have trained to do for so long, the men are a-whirl with action. These massive guns are much like the guns on the English battleships now cruising in front of them, with one key difference â there is no hydraulic assistance to raise the shells into the shell cradles. Instead, the shells are lifted by hoists. Then they are rammed by mechanical and physical force into the breech before the breechblock is shut.

Upon hearing the captain's order, the men fire and a massive explosion roars forth â BOOOOOM! The gun recoils and a shell flies out of the muzzle towards

Queen Elizabeth

and ⦠and within seconds ⦠falls uncomfortably short.

The Turks rush up to the platform, remove the expended powder bags and swab the barrel for embers. A new shell is hoisted up and the process repeated.

As they are doing so ⦠BOOM! Another giant German shell bursts forth. Again, no luck.

What the shots do achieve, however, is to draw significant retaliation from the fleet, which had hitherto been shooting blind (and often at the inky cloud of a decoy sewer pipe gun). But now, as the sound echoes and the smoke drifts up from Rumeli Mecidiye Fort, they have a set target.

As Captain Hilmi would recall, âBecause I started to shoot alone, nearly all the ships turned their fire on my fort.'

Within minutes, the battery is âsmothered in smoke from all the shells that landed ⦠The artillery sergeants could not even see the sea, let alone their targets.'

17

On the ships, it soon becomes apparent: the barrage of shells upon the forts is working, and the firing from the closest forts upon the British Fleet is falling â¦

On them once more.

Oh Lord.

Time and time again, just when it appears that a fort is taken out of the battle, suddenly its guns roar once more, and the ships are again under attack. Whether it is a Turkish ploy or the gunners are scrambling to regroup, the reason for their temporary silence is not clear. But the result is the same. For from one minute to the next it is never clear to the fleet just where the next shells will be coming from.

Now at midday, Admiral de Robeck judges it the right time for the French squadron to move further up the Straits, supported from behind by

Queen Elizabeth

and company.

The scene, as Winston Churchill would later describe it, is one âof terrible magnificence. The mighty ships wheeling, manoeuvring and firing their guns, great and small, amid fountains of water, the forts in clouds of dust and smoke pierced by enormous flashes, the roar of the cannonade reverberating back from the hills on each side of the Straits, both shores alive with the discharges of field guns; the attendant destroyers, the picket-boats darting hither and thither on their perilous service â all displayed under shining skies and upon calm blue water, combined to make an impression of inconceivable majesty and crisis.'

18

Around 1 pm, the line of French ships is coming into range of the Intermediate Defences â and this time it is the Turkish guns that take a toll as one shell hits

Gaulois

in its heart. So quickly does the grievously stricken ship take on water that all it can do is begin to retreat, and later beach herself outside the Straits. Both

Agamemnon

and

Inflexible

are also badly damaged, though both remain operational.

The fire coming from the mobile howitzer batteries on the shores continues to worry the mighty ships. Whereas the forts present obvious targets, and it is easy to see where their guns are positioned, who knows where the howitzers

are?

For the most part they are well secreted, and even if the ships are able to draw a bead on them, it is an easy matter for their commanders to whip the buffalo teams into action â yes, a team of buffalo is used to pull the howitzers â to change positions and keep firing from a new position.

Suddenly, just after 1.15 pm,

Suffren

shakes with a shattering roar as smoke billows and alarms go off. And the ship shakes again. And again! Several heavy shells land in succession, exploding with a blast of flame and seething shrapnel that knocks out a gun turret and incinerates the crew inside. Worse, a molten piece of debris falls into the port magazine, and the flames and burning gases are soon spreading. The explosion of the entire ship is imminent. With many of the communication systems down, it is simply not possible for the men to get a firm direction on crucial decisions. The ship begins to list under the weight of water flooding in, fire rages between decks, and men stumble and scream in agonies untold. The junior quarter-master who is responsible for the ammunition store most likely to blow, François Lannuzel, just 23 years old, reacts. All those who can must leave the store immediately, he orders, so he can face this alone.