Gandhi & Churchill (66 page)

Read Gandhi & Churchill Online

Authors: Arthur Herman

The beginning of Gandhi’s Salt March at Sabarmati, March 1930. The smokestacks of Ahmedabad can be seen in the distance. (GandhiServe/Peter Rühe)

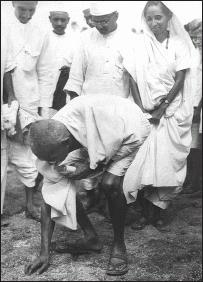

This photograph is usually identified as Gandhi making salt at Dandi at the end of his epic march, on April 6, 1930. In fact, it was taken four days later, at Bhimpur. (V. Jhaveri/Peter Rühe)

Salt satyagraha in Bombay, as dark-clothed Indian police charge with lathis. (

Daily Herald

Archive/Peter Rühe)

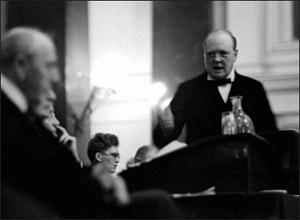

Churchill speaks against Indian independence to meeting of the Indian Empire Society, December 10, 1930. “It must be made plain that the British nation has no intention of relinquishing its mission in India or failing in its duty to the Indian masses.” (Fox Photos/Getty Archives)

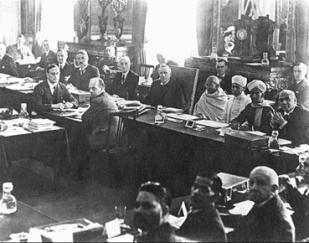

Gandhi (with Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald [sixth from left] and Sir Samuel Hoare [center] sitting to the Mahatma’s right) at second Round Table Conference, London 1931. Discussions there convinced Gandhi that only passive resistance, or

satyagraha,

could give India complete independence. (V. Jhaveri/Peter Rühe)

A left-wing cartoonist’s view of Churchill against the Government of India Bill, 1933. Churchill’s bitter five-year battle against the bill alienated him from his own Conservative party, and drove him into the political wilderness. (Broadwater/Churchill Archives)

Gandhi with the

enfant terrible

of Indian nationalist politics, Subhas Chandra Bose (center), at the Indian National Congress meeting in 1938. Gandhi feared Bose’s radicalism and tried unsuccessfully to keep him from being re-elected president of the INC. Here he tries to put the best face on their relationship. The face of Gandhi’s deputy Vallalabhai Patel (right) tells a different story. (Hulton/Getty Archives)

The crux of the matter was the communal problem and the need to reassure India’s multiple minorities that their rights would be respected in a democratic state dominated by a quarter-billion Hindus. Gandhi chaired the Committee on Minorities meetings of late September and early October, where representatives for Muslims, Sikhs, Anglo-Indians, and untouchables bickered over separate electorates province by province. It was a tedious and dismal exercise. Elaborate formulas were proposed for deciding who would vote for how many seats in the Punjab, the United Provinces, and Bengal.

20

The debate raged for hours, to no avail, over what had become an elaborate game of constitutional musical chairs. No group was willing to give up its claim to reserved seats or votes, not even in exchange for more seats and votes in the future, for fear that someone else might steal their original allotment.

Gandhi himself would consent to separate electorates for only two groups, Muslims and Sikhs. But other minorities insisted on separate representation as well, while Gandhi horrified Hindu delegates by suggesting they should give Muslims “a blank check” on the question of separate voting. The Muslim delegates then demanded that all communal questions be settled before the constitution was drawn up—whereas others, including Gandhi, saw that issue as

part

of drawing up a constitution.

21

In the end discussion collapsed on what to do about the Punjab, where Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs all vied for power in a provincial legislature that did not yet exist. On October 8 Gandhi and the Committee on Minorities had to report their failure to the general conference. William Shirer watched with consternation: “Hindus, Moslems, Sikhs, Christians, and untouchables fairly flew at each other’s throats.”

22

If anything seemed calculated to show the British delegates that Indians were incapable of peaceful self-rule, this was it.

The bitterest words toward Gandhi came from Dr. B. R. Ambedkar. Born in the garrison town of Mhow and the son of an untouchable soldier, Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar had been educated in America at Columbia University. A Mahar dalit by caste, “the highest of the lowest,” he was now the leading spokesman for India’s estimated fifty million untouchables.

23

He respected Gandhi’s desire to lift the burden of shame and discrimination from India’s depressed classes, but he also resented Gandhi’s attitude of knowing what was best for them. Ambedkar knew firsthand the hardships of being an untouchable; Gandhi did not. As even Muriel Lester had to point out, “Who was likely to know best where the shoe pinched?”

24

However, Gandhi claimed that untouchables were an indissoluble part of the Hindu nation and therefore were part of Congress. Special electoral protections were unnecessary. Ambedkar vehemently disagreed, accusing Gandhi of committing a “breach of faith,” dealing dishonestly, and handling the whole minorities problem in an “irresponsible” manner. It was a bitter tirade; Gandhi murmured only a sarcastic “Thank you, sir,” in reply. But that evening he confessed: “This has been the most humiliating day of my life.”

25

He wrote a note to Lord Irwin: “It does not dismay me. I shall toil on.” But he knew it was hopeless.

26

The impasse was complete. The only possible umpire were the British, but Gandhi rejected that solution at once. He blamed the British for the entire problem of communal strife in India, just as he blamed them for India’s poverty, its famines, and its cultural and economic dependency. “I have not a shadow of a doubt,” he said on October 8, “that the iceberg of communal differences will melt under the warmth of the sun of freedom.” It was a gross oversimplification of history, but it seemed to gain credence when, over the September 18 weekend, the British government without warning had devalued the rupee.

27

Industry, businesses, and pensioners in India all took it on the chin. Even wealthy Indians were left to conclude that the sooner India separated from Britain, the better.

Time for reaching an amicable solution was running out. Less than two weeks after Gandhi had to admit his “failure” to find a solution to the communal tangle, Britain held yet another general election. This one resulted in a Conservative sweep; Labour lost almost 236 seats. Ramsay MacDonald still clung onto his premiership, but of the National Government’s 554 members, 473 were now Tories. The election of October 27, 1931, brought “the most Conservative Parliament of the century.”

28

Churchill himself had almost doubled his vote in his constituency. Chances that Britain would “give away” India anytime soon seemed to fade.

The Round Table Conference met for another fruitless month. On December 1 Prime Minister MacDonald addressed the final session. His Majesty’s Government, he stated, was still committed to the process of granting India “responsible government” and self-rule in an all-India federation, but Britain might have to decide how to handle the Muslims and the minorities by itself.