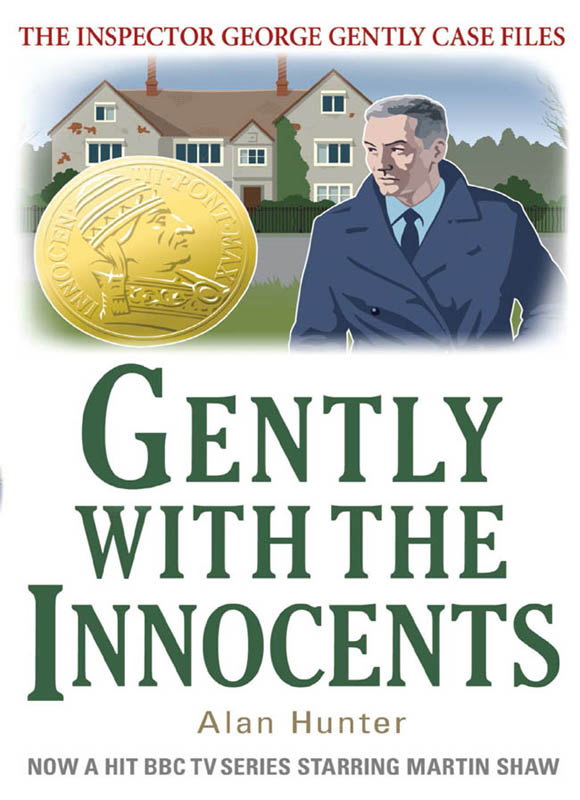

Gently with the Innocents

Read Gently with the Innocents Online

Authors: Alan Hunter

Alan Hunter

was born in Hoveton, Norfolk, in 1922. He left school at the age of fourteen to work on his father’s farm, spending his spare time sailing on the Norfolk Broads and writing nature notes for the

Eastern Evening News.

He also wrote poetry, some of which was published while he was in the RAF during the Second World War. By 1950, he was running his own bookshop in Norwich. In 1955, the first of what would become a series of forty-six George Gently novels was published. He died in 2005, aged eighty-two.

The Inspector George Gently series

Gently Does It

Gently by the Shore

Gently Down the Stream

Landed Gently

Gently Through the Mill

Gently in the Sun

Gently with the Painters

Gently to the Summit

Gently Go Man

Gently Where the Roads Go

Gently Floating

Gently Sahib

Gently with the Ladies

Gently North-West

Gently Continental

Gently at a Gallop

Alan Hunter

Constable & Robinson Ltd

55–56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

First published in the UK by Cassell & Company Ltd., 1970

This paperback edition published by Robinson,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd., 2013

Copyright © Alan Hunter 1970

The right of Alan Hunter to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or to actual events or locales is entirely coincidental

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication

Data is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78033-945-0 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-47210-463-2 (ebook)

Typeset by TW Typesetting, Plymouth, Devon

Printed and bound in the UK

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Cover image by David Woodroffe; Cover by

JoeRoberts.co.uk

The characters and events in this book are fictitious; the locale is sketched from life.

Let me add to the above legend that ‘Harrisons’ is a real house. For the purpose of the narrative I removed it from its village and placed it in the town I have called Cross, but a little detective work with this book and a map may suggest its location to the curious. The quotation given in the text is only slightly doctored, and the description of the house is accurate – except for one minor feature.

The house was for sale when I explored it. I believe the price asked was very reasonable.

A. H.

T

HE TELEPHONE RANG

out in the hall and Gently looked up frowning. Praise the Lord, not tonight – after the sort of day he’d been having!

In Elphinstone Road the rain was still pelting as it had been pelting all day: that chill, penetrating stuff which they kept for the back-end of November. He’d come in sodden, feeling old, and had downed a couple of rum-and-lemons. Mrs Jarvis was out. He’d had to knock himself up a poached egg and a pot of tea.

Now, settled by the fire in his den, he was beginning to feel dry at last, and he didn’t want to know about Assistant Commissioners with bad cases of murder on their minds.

‘For you, sir.’

Mrs Jarvis poked her unexpressive face round the door.

‘Who is it?’

‘Didn’t catch his name, sir. Ain’t none of your lot by the sound of him.’

She’d just come in. Her head was swathed in a glinting pixie-hood of grey plastic.

‘All right, I’ll take it.’

Mrs Jarvis sniffed and drew her head back from the door.

Gently hauled the extension phone over.

‘Chief Superintendent Gently . . .’

For a moment he could hear nothing but the sound of irregular breathing.

‘Yes?’

‘I . . . I . . .’

‘Speak up!’

‘I—please, I want to talk to you.’

‘Who are you?’

The name sounded like ‘piecemeal’: no wonder Mrs Jarvis didn’t get it.

‘So what’s the trouble?’

‘It’s . . . the police . . .’

‘Yes?’

‘They think I’ve murdered my uncle.’

Gently sighed. ‘And did you?’ he asked.

‘No!’

‘So why bother me?’

There were confused sounds at the other end, as though the caller were shifting his grip on the receiver. Gently could hear traffic. The man was probably in a call-box.

‘Look, I must talk to you . . . please! It isn’t as simple as it sounds. Fazakerly told me—’

‘Fazakerly?’

‘Yes. He said you were related . . .’

Gently grimaced. John Fazakerly was a remote connection of his sister’s husband – a ne’er-do-well who had dragged Gently into a case that was none of his business. Not much of a recommendation to quote.

‘I don’t know him, of course . . . my firm sold the lease of his flat. But he’d mentioned you . . . about his wife . . . and I had to talk to someone . . .’

‘And he suggested me.’

‘Yes.’

‘Surely a lawyer would be more appropriate?’

‘But you don’t understand!’

Gently yawned.

‘He said . . . if I were innocent . . . come to you.’

A chunk of coal fell against the bars and lay hissing a geyser of white smoke. In the phone Gently distinctly heard gears being changed. Traffic lights? A junction?

‘Where are you speaking from?’

‘I’m in a call-box. At Tally-Ho Corner.’

‘I see.’

‘Please! If you could give me just ten minutes . . .’

Gently shrugged at nobody. ‘Well, since you’re out here.’

‘I can see you?’

‘For what it’s worth.’

‘Thanks . . . oh, thanks!’

Gently dropped the phone with a grunt.

His name was Peachment, Adrian Peachment, and he gave his age as twenty-six, a rather fey-looking young man with dark hair and shining dark eyes. Not a Londoner. Even over the phone you could spot a broadness in his speech. Yet he dressed in the current semi-military vogue and wore his hair in a nest that brushed his collar. He had parked a Mini with a recent date-letter under the tear-drop lamp across the street.

‘I’m terribly grateful, sir . . .’

He had left with Mrs Jarvis a short alpaca coat and a deer-stalker.

‘Oh, sit down.’

‘I wouldn’t have imposed—’

‘Do you smoke?’

He lit a cigarette jerkily, using a butane lighter.

Gently himself lit his pipe.

‘First, your troubles are none of my business. If the police are dealing with your case I couldn’t interfere anyway.’

‘It isn’t that—’

‘Listen to me! You’ll probably only make matters worse. If you drop something I shall have to report it. You’d be far better off if you talked to your lawyer. You have one, haven’t you?’

‘Well . . . no.’

‘Why not?’

‘At this stage . . . I didn’t think . . .’

‘What do you mean – ‘‘at this stage’’?’

‘The coroner . . . at the inquest they seemed satisfied.’

Gently breathed smoke, staring at him.

‘Didn’t you say you were under suspicion?’

‘Yes.’ Peachment flicked his cigarette nervously. ‘Only the coroner . . . they’re not sure it was murder.’

Not sure it was murder! Gently chewed on his pipe-stem, eyeing the young man with little friendliness. For this he’d interrupted his snug evening, and the book lying open on the side-table . . .

‘Just give me the facts.’

‘Yes, of course.’

Peachment sat like a woman, his knitted legs turned sideways. He had a young-old face, long, hollow-cheeked, and long-fingered hands with bony joints.

‘You see, they found him dead . . . actually, the milkman . . .’

‘Who?’

‘My uncle, James Peachment. He was seventy, you know, and living alone. They found him dead at the foot of some stairs.’

‘In London?’

‘No. No, in Cross . . . that’s a little town on the Northshire border. Uncle always lived there . . . my family . . . I’m up here now, I’ve a job in Kensington.’

‘What did the report say?’

‘A fractured skull.’

‘So?’

Peachment jigged his cigarette. ‘There was other bruising. On the arms, legs, everywhere. As though someone had beaten the old boy up.’

Gently puffed slowly. ‘This happened in his house?’

‘Yes. It’s a queer old place called Harrisons. Elizabethan, something like that. All beams and passages and funny rooms. Well, the milkman found him at the foot of this staircase. It only goes to an empty room. And nothing taken as far as I knew . . . they made me go through the place, to check.’

‘Had it been broken into?’

Peachment shook his head. ‘They wouldn’t need to break in if they knew the place. One of the back doors opens into a lean-to and doesn’t even have a bolt. Of course it’s mad . . . but that’s in the country. People don’t bother so much there.’

‘Carry on.’

‘Well . . . the police were awkward. You see, I was down there the day it happened. My girl-friend lives there. I called on Uncle. They got my finger-prints off one of the door-knobs. Then there’s the bit about me inheriting – my people are dead, so it comes to me. And, well . . . I don’t have a very good alibi, either. You can see their point. I could have done it.’

Gently eased himself back in his favourite chair. Perhaps there was something in it, after all! With a case like that lined-up against him, you might excuse any man for getting jumpy.

‘What is your alibi, just for the record?’

Peachment’s neck was flushing a little.

‘Actually . . . Jeanie and I had a row. I cleared off back here not long after tea.’

‘And that doesn’t cover you?’

‘No, not really. They say he died about eight p.m. Well, I wasn’t back here till close on ten, and nobody saw me get in anyway. You see, I have a flat.’

Yes, indeed, Gently saw. He blew a couple of casual smoke-rings and gazed at Peachment almost benignly.

‘But they haven’t arrested you?’

‘Well . . . no. I mean, the coroner returned an open verdict. Uncle could have got the bruises falling down the stairs – he

could

have done. It’s just possible.’

‘Then what’s your worry?’

Peachment’s eyes widened. ‘The police don’t think he died by accident.’

‘What about you?’

‘I

know

he didn’t. And that’s why I wanted to talk to you.’

He felt carefully in his breast pocket and took out a small, folded manila envelope.

‘This is why Uncle was murdered,’ he said. ‘And the reason why they beat him up.’

Gently took the envelope. The long fingers were trembling as they handed it over. Though small, and folded smaller, the envelope was unexpectedly heavy. Gently weighed it in his hand a moment.

‘A coin?’

‘A medal actually . . . that one.’

‘You mean there are others?’

‘Yes. I’m sure of it. But that’s the only one left.’