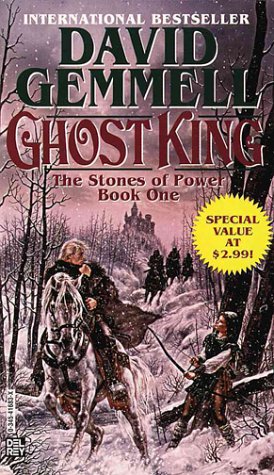

Ghost King

Authors: David Gemmell

Stones of Power 1 - Ghost King

The boy stared idly at the cold grey walls and wondered if the castle dungeons could be any more inhospitable "than this chill turret room, with its single window staring like an eye into the teeth of the north wind. True there was a fire glowing in the hearth, but it might as well have been one of Maedhlyn's illusions for all the warmth it supplied. The great grey slabs sucked the heat from the blaze, giving nothing in return save a ghostly reflection that mocked the flames.

Thuro sat on the bed and wrapped his father's white bearskin cloak about his own slender shoulders.

'What a foul place,' he said, closing his eyes and pushing the turret room from his mind. He thought of his father's villa in Eboracum, and of the horse meadows beyond the white walls where mighty Cephon wintered with his mares. But most of all he pictured his own room, cosy and snug away from the bitter winter winds and filled with the love of his young life: his books, his glorious books. His father had refused him permission to bring even one tome to this lonely castle, in case the other war leaders should catch the prince reading and know the king's dark secret. For while it might be well-known in Caerlyn Keep that the boy Thuro was weak in body and spirit, the king's retainers guarded the sad truth like a family shame.

Thuro shivered and left the bed to sit on the goatskin rug before the fire. He was as miserable now as he had ever been. Far below in the great hall of Deicester Castle his father was attempting to bond an alliance against the barbarians from across the sea, grim-eyed reavers who had even now established settlements in the far south from which to raid the richer northlands. The embassy to Deicester had been made despite Maedhlyn's warnings. Thuro had not wished to accompany his father either, but not for fear of dangers he could scarce comprehend. The prince disliked the cold, loathed long journeys on horseback and, more importantly, hated to be deprived of his books even for a day - let alone the two months set aside for the embassy.

The door opened and the prince glanced up to see the tall figure of Gwalchmai, his brawny arms bearing a heavy load of logs. He smiled at the lad and Thuro noted with shame that the retainer wore but a single woollen tunic against the biting cold.

'Do you never feel the chill, Gwalchmai?'

'I feel it,' he answered, kneeling to add wood to the blaze.

'Is my father still speaking?'

'No. When I passed by Eldared was on his feet.'

'You do not like Eldared?'

'You see too much, young Thuro; that is not what I said.'

But you did, thought Thuro. It was in your eyes and the slight inflection when you used his name. He stared into the retainer's dark eyes, but Gwalchmai turned away.

'Do you trust him?' asked the boy.

'Your father obviously trusts him, so who am I to offer opinions? You think the king would have come here with only twenty retainers if he feared treachery?'

'You answer my question with questions. Is that not evasive?'

Gwalchmai grinned. 'I must get back to my watch. But think on this, Thuro: it is not for the likes of me to criticise the great. I could lose the skin from my back - or worse, my life.'

'You think there is danger here?' persisted the prince.

'I like you, boy, though only Mithras knows why. You've a sharp mind; it is a pity you are weakly. But I'll answer your question after a fashion. For a king there is always danger; it is a riddle to me why a man wants such power. I've served your father for sixteen years and in that time he has survived four wars, eleven battles and five attempts on his life. He is a canny man. But I would be happier if the Lord Enchanter were here.'

'Maedhlyn does not trust Eldared; he told my father so.'

Gwalchmai pushed himself to his feet. 'You trust too easily, Thuro. You should not be sharing this knowledge with me - or with any retainer.'

'But I can trust you, can I not?'

'How do you know that?' hissed Gwalchmai.

'I read it in your eyes,' said Thuro softly. Gwalchmai relaxed and a broad grin followed as he shook his head and tugged on his braided beard.

'You should get some rest. It's said there's to be a stag-hunt tomorrow.'

‘I’ll not be going,' said Thuro. 'I do not much like riding.'

'You baffle me, boy. Sometimes I see so much of your father in you that I want to cheer. And then . . . well, it does not matter. I will see you in the morning. Sleep well.'

'Thank you for the wood.'

'It is my duty to see you safe.' Gwalchmai left the room and Thuro rose and wandered to the window, moving aside the heavy velvet curtain and staring out over the winter landscape: rolling hills covered in snow, skeletal trees black as charcoal. He shivered and wished for home.

He too would have been happier if Maedhlyn had journeyed with them, for he enjoyed the old man's company and the quickness of his mind - and the games and riddles the Enchanter set him. One had occupied his mind for almost a full day last summer, while his father had been in the south routing the Jutes. Thuro had been sitting with Maedhlyn in the terraced garden, in the shade cast by the statue of the great Julius.

There was a prince,' said Maedhlyn, his green eyes sparkling, 'who was hated by his king but loved by the people. The king decided the prince must die, but fearing the wrath of the populace he devised an elaborate plan to end both the prince's popularity and his life. He accused him of treason and offered him Trial by Mithras. In this way the Roman god would judge the innocence or guilt of the accused.

'The prince was brought before the king and a large crowd was there to see the judgement. Before the prince stood a priest holding a closed leather pouch and within the pouch were two grapes. The law said that one grape should be white, the other black. If the accused drew a white grape, he was innocent. A black grape meant death. You follow this, Thuro?'

'It is simple so far, teacher.'

'Now the prince knew of the king's hatred and guessed, rightly, that there were two black grapes in the pouch. Answer me this, young quicksilver: How did the prince produce a white grape and prove his innocence?'

'It is not possible, save by magic.'

'There was no magic, only thought,' said Maedhlyn, tapping his white-haired temple for emphasis. 'Come to me tomorrow with the answer.'

Throughout the day Thuro had thought hard, but his mind was devoid of inspiration. He borrowed a pouch from Listra the cook, and two grapes, and sat in the garden staring at the items as if in themselves they harboured the answer. As dusk painted the sky Trojan red, he gave up. Sitting alone in the gathering gloom he took one of the grapes and ate it. He reached for the other - and stopped.

The following morning he went to Mae-dhlyn's study. The old man greeted him sourly - having had a troubled night, he said, with dark dreams.

'I have answered your riddle, master,' the boy told him. At this the Enchanter's eyes came alive.

'So soon, young prince? It took the noble Alexander ten days, but then perhaps Aristotle was less gifted than myself as a tutor!' He chuckled. 'So tell me, Thuro, how did the prince prove his innocence?'

'He put his hand into the pouch and covered one grape. This he removed and ate swiftly. He then said to the priest, “I do not know what colour it was, but look at the one that is left.” '

Maedhlyn clapped his hands and smiled. 'You please me greatly, Thuro. But tell me, how did you come upon the answer?'

'I ate the grape.'

'That is good. There is a lesson in that also. You broke the problem down and examined the component parts. Most men attempt to solve riddles by allowing their minds to leap like monkeys from branch to branch, without ever realising that it is the root that needs examining. Always remember that, young prince. The method works with men as well as it works with riddles.'

Now Thuro dragged his thoughts from the golden days of summer back to the bleak winter night. He removed his leggings and slid under the blankets, turning on his side to watch the flickering flames in the hearth.

He thought of his father - tall and broad-shouldered with eyes of ice and fire, revered as a warrior leader and held in awe even by his enemies.

'I don't want to be a king,' whispered Thuro.

*

Gwalchmai watched as the nobles prepared for the hunt, his emotions mixed. He felt a fierce pride as he looked upon the powerful figure of his king, sitting atop a black stallion of seventeen hands. The beast was called Bloodfire and one look in its evil eyes would warn any horseman to beware. But the king was at ease, for the horse knew its master; they were as alike in temperament as brothers of the blood. But Gwalchmai's pride was mixed with the inevitable sadness of seeing prince Thuro beside his father. The boy sat miserably upon a gentle mare of fifteen hands, clutching his cloak to his chest, his white-blond hair billowing about his slender ascetic face. Too much of his mother in him, thought Gwalchmai, remembering his first sight of the Mist Maiden. It was almost sixteen years ago now, yet his mind's eye could picture the queen as if but an hour had passed. She rode a white pony and beside the warrior king she seemed as fragile and out of place as ice on a rose. Talk among the retainers was that their lord had gone for a walk with Maedhlyn into a mist-shrouded northern valley and vanished for eight days. When he returned his beard had grown a full six inches and beside him was this wondrous woman, with golden hair and eyes of swirJing grey like mist on a northern lake.

At first many of the people of Caerlyn Keep had thought her a witch, for even here the tales were told of the Land of Mist, a place of eldritch magic. But as the months passed she charmed them all with her kindness and her gentle spirit. News of her pregnancy was greeted with great joy and instant celebration. Gwalchmai would never forget the raucous banquet at the Keep, nor the wild night of pleasure that followed it.

But eight months later Alaida, the Mist Maiden, was dead and her baby son hovering on the brink of death, refusing all milk. The Enchanter Maedhlyn had been summoned and he, with his magic, saved young Thuro. But the boy was never strong; where the retainers had hoped for a young man to mirror the king, they were left with a solemn child who abhorred all manly practices. Yet enough of his mother's gentleness remained to turn what would have been scorn into a friendly sadness. Thuro was well-liked, but men who saw him would shake their heads and think of what might have been. All this was on Gwalchmai's mind as the hunting party set off, led by Lord Eldared and his two sons Gael and Moret.

The king had never recovered from the death of Alaida. He rarely laughed and only came alive when hunting either beasts or men. He had plenty of opportunity in those bloody days for the Saxons and Jutes were raiding in the south and the Norse sailed their Wolfships into the deep rivers of the East Country. Added to this there were raiders aplenty from the smaller clans and tribes who had never accepted the right of the Romano-British warlords to rule the ancient lands of the Belgae, the Iceni and the Cantii.

Gwalchmai could well understand this viewpoint, being pure-blood Cantii himself, born within a long stone's throw of the Ghost Cliffs.

Now he watched as the noblemen cantered towards the wooded hills, then returned to his quarters behind the long stables. His eyes scanned the Deicester men as they lounged by the alehouse and he began to grow uneasy. There was no love lost between the disparate groups assembled here, though the truce had been well-maintained - a broken nose here, a sprained wrist there, but mostly the retainers had kept to themselves. But today Gwalchmai sensed a tension in the air, a brightness in the eyes of the soldiers.

He wandered into the long room. Only two of the king's men were here, Victorinus and Caradoc. They were playing knuckle-bones and the Roman was losing, with good grace.

'Rescue me, Gwal,' said Victorinus. 'Save me from my stupidity.'

"There's not a man alive who could do that!' Gwalchmai moved to his cot and his wrapped blankets. He drew his gladius and scabbard from the roll and strapped the sword to his waist.

'Are you expecting trouble?' asked Caradoc, a tall rangy tribesman of Belgae stock.

'Where are the others?' he answered, avoiding the question.

'Most of them have gone to the village. There's a fair organised.' 'When was this announced?' 'This morning,' said Victorinus, entering the conversation. 'What has happened?'

'Nothing as yet,' said Gwalchmai, 'and I hope to Mithras nothing does. But the air smells wrong.'

'I can't smell anything wrong with it,' responded Victorinus.

'That's because you're a Roman,' put in Caradoc, moving to his own blanket roll and retrieving his sword.

‘I’ll not argue with a pair of superstitious tribesmen, but think on this: if we walk around armed to the teeth, we could incite trouble. We could be accused of breaking the spirit of the truce.'

Gwalchmai swore and sat down. 'You are right, my friend. What do you suggest?'

Victorinus, though younger than his companions, was well respected by the other men in the King's Guards. He was steady, courageous and a sound thinker. His solid Roman upbringing also proved a perfect counterpoint to the unruly, explosive temperaments of the Britons who served the king.

'I am not altogether sure, Gwal. Do not misunderstand me, for I do not treat your talents lightly. You have a nose for traps and an eye that reads men. If you say something is amiss, then I'll wager that it is. I think we should keep our swords hidden inside our tunics and wander around the Keep. It may be no more than a lingering ill-feeling amongst the Deicester men for Caradoc here taking their money last night in the knife-throwing tourney.'

'I do not think so,' said Caradoc. 'In fact, I thought they took it too well. It puzzled me at the time, but it did not feel right. I even slept with one hand on my dagger.'

'Let us not fly too high, my friends,' said Victorinus. 'We will meet back here in an hour. If there is danger in the air, we should all get a sniff of it.'

'And what if we find something?' asked Caradoc.