Ghost Messages (18 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Guest

Tags: #Finians, #Novel, #Chapter Book, #Middle Reader, #Historical, #Ghost, #Mystery, #Adventure, #Atlantic Crossing, #Telegraph Cable, #Irish

“Captain Anderson, would you answer one more question?”

He nodded kindly. “Why, certainly, my dear.”

“Last year, I was friends with the bash boy in the hold, but this trip, he wasn’t on board. Do you know what happened to him?”

Captain Anderson looked puzzled. “I remember you mentioning something about this fellow before. You must be mistaken. There was no bash boy aboard, then or now.”

She shook her head adamantly. “Mistaken? No, sir. Davy worked with a riveter on the iron plates belowdecks. Why, I talked with him there many times.”

“Miss O’Connor,” the captain began indulgently, “I am quite certain there was no bash boy in the hold. There hasn’t been since the last plates were affixed, in 1857.”

A frown creased his brow and he seemed to be recalling some forgotten fragment of information. “There is, however, a legend that has attached itself to the

Great Eastern

. It tells of a riveter and his bash boy who fell while working between the double hulls when building the ship. The calamitous noise of two hundred riveters hammering away drowned out their cries, and they were walled up alive. It is said you can hear a ghostly hammering belowdecks as they continue to pound in their phantom rivets.”

Ailish felt dizzy. A long-ago memory surfaced, of Ma telling her it was possible for fey souls like them to speak to someone who had passed over, gone to the other side. She’d said it started with a numb sort of tingling that turned into a white-hot heat, like a fever were burning inside.

The last time she and Davy had spoken, she had felt that heat.

A thousand clues she’d missed at the time flooded her head. His detailed stories about the building of the

Great Eastern,

clear as if he’d been there; his magic trick with

the gaslights, and the way he’d appeared in the dark passage just when she’d needed him. And her name, she couldn’t remember ever telling him, yet he knew it. His old-fashioned clothes – had she ever seen him in anything but those same faded breeches? And all the mysterious notes – on every one, the ink had blurred and faded away.

She remembered the day she’d wanted to touch him, and he’d become so angry, spouting that nonsense about Ailish thinking he wasn’t good enough for her. He hadn’t wanted her to touch him because he knew she

couldn’t

touch him!

And in all the time she’d been with Davy, she had never seen him any place but belowdecks. The reason was now so obvious. And his answer to her – “

We’re as much a part of the Great Eastern as the iron plates and rivets holding her together.”

It had been the literal truth.

Their last meeting tumbled into her mind. Her invitation for him to leave the ship and join her and Da – it had seemed crazy even at the time, so perhaps she had known, deep in her bones.

Davy Jones was a, a …

She couldn’t say it.

“That is truly a tragic tale, Captain Anderson.” She smiled tremulously. “If anyone asks, the riveter was named Charlie and the bash boy who died was a remarkable young man by the name of David Jones.”

– - • – –

Later, standing beside her da on the deck of the

launch, Ailish looked back at the mighty vessel. It took a long time to get distance enough to see it entirely. The

Great Eastern

was a ship like no other and a true leviathan of the seas.

At last, shading her eyes against the morning sun’s glare, Ailish was able to take it all in. Then she saw, high up on the catwalk, a solitary figure silhouetted against the brilliant blue sky.

The figure waved.

What had Davy said?

“I don’t go on deck unless it’s for someone incredible and extraordinary.”

Smiling at the compliment, she waved back as hard as she could, then watched as he faded into thin air.

Ailish slipped a hand into her pocket and curled her fingers protectively around the rusted old rivet nestled at the bottom. Tears sparkled on her lashes as she remembered his words.

As long as you keep a loved one in your heart, they are with you always.

“You will be with me always, Davy Jones,” she whispered. “You and your ghost messages.”

Author’s Note

While speaking to students on the brilliant devices we use to chat to friends today I realized they had no idea how it all began. The marvels of communication we enjoy in the 21st century make it difficult to fathom that it wasn’t always as it is now. Text messaging, e-mails, satellites and high speed Internet are built upon much humbler beginnings and Canada, especially Newfoundland, played an important role. I decided to investigate and

Ghost Messages

is the result of that snooping into the dusty past.

Ghost Messages

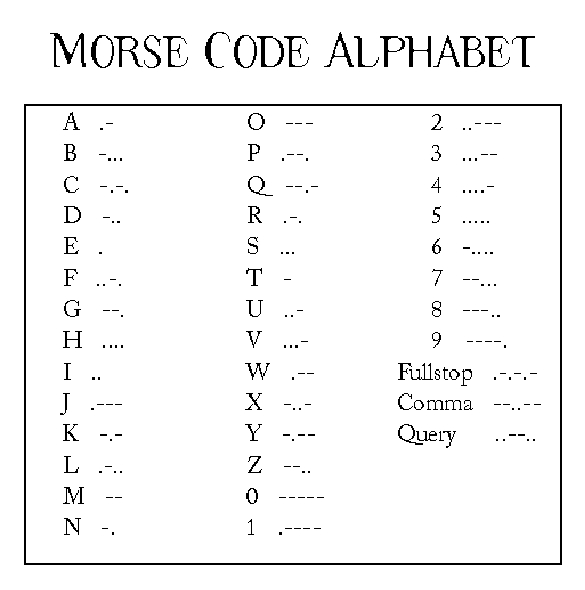

tells of the 1865 attempt to lay the first trans-Atlantic cable which would connect the two halves of the world with instant communication. The communication wasn’t digital; it wasn’t fibre optics or telephone; in fact, it wasn’t even a human voice. It was Morse code transmitted for 2300 nautical miles in dots and dashes along a one-inch thread composed of seven strands of fragile copper wire! (I am pleased to say I have a piece of that original wire cable, dredged up from the bottom of the ocean, and enjoy showing students when I give presentations in schools.)

At the time, a transatlantic cable was thought to be an impossibility – science fiction – but this was an age of miracles when some of the greatest men of vision and science worked together to create miracles of their own.

Their names are synonymous with world-changing advances: Cyrus Field, Samuel Canning, Isambard Brunel, Daniel Gooch, William Thomson (later known as Lord Kelvin), Samuel Morse and Michael Faraday. All of these gentlemen, and many more, contributed to this project.

The

Great Eastern

was a remarkable ship – it was five times larger than any vessel built, was seven hundred feet long and utilized three methods of propulsion – sail, propeller and paddlewheel. The innovative double hull made it unsinkable and nearly indestructible, requiring the invention of the wrecking ball to take it apart.

On that first cable-laying attempt in 1865, one of the greatest captains to sail the blue sea was at the helm, Captain James Anderson. He really did manage not once, but numerous times, to find the one-inch cable when it was lost miles below on the ocean floor. Suspected sabotage by the Fenians is also recorded in the history books, and it was eventually discovered that the cable itself had done the damage when brittle shards of the outer casing imbedded themselves into the wire, shorting the signal.

The legend of the ghost aboard the

Great Eastern

is well documented in the ship’s lore; and when the ship was finally dismantled, the skeletons of both the riveter and his bash boy were found between the hulls, where they had fallen to their deaths when the ship was being built. I have taken a little literary licence by naming these forgotten souls as their true identities have disappeared into the mists.

As a writer, I could not have dreamed up a more exciting plot. History itself has provided the people, setting and dramatic events complete with a ship of legend, ghosts, broken cables, storms, and sabotage. It is my hope that this book will instill in you a sense of wonder and respect for those intrepid scientists and explorers on whose inventions and discoveries our modern communications world is built. The next time you e-mail, text message or Twitter a friend, remember it all began long ago with a fragile thread thousands of miles long and those whispered “ghost messages.”

Glossary of Nautical Terms

Ahoy!:

A very old and traditional greeting for hailing other vessels; originally a Viking battle cry.

Chewing the Fat:

Having a long chat. “God made the vittles but the devil made the cook” was a popular saying used by seafaring men in the 19th century, when salted beef was the staple diet aboard ship. This tough cured beef, suitable only for long voyages when nothing else would keep (remember, there was no refrigeration) required prolonged chewing to make it edible. Men often chewed one chunk for hours, just as if it were chewing gum, and referred to this practice as “chewing the fat.”

Devil to Pay or Paying the Devil:

The expected unpleasant result of some action that has been taken. Sailors adopted the colourful idea of having to pay the devil for whatever fun you had and applied it to the most unpleasant tasks aboard a wooden ship. Caulking (sealing) seams and gaps in the ship was one of them: and it must certainly have been hellish to be suspended high above sea on the outside of a ship, or up to your knees in stinking bilgewater deep in the hold, using shredded rope and sticky black pitch to keep the saltwater out.

Fathom:

A span of six feet. Fathom was originally a land-measuring term, derived from the Ango-Saxon word “faetm” meaning to embrace. In those days, most measurements were based on average size of parts of the body, such as the hand (horses are still measured this way) or the foot (that’s why 12 inches are so named). A fathom was the average distance from fingertip to fingertip of the outstretched arms of a man; or, as it was defined by an act of Parliament, “the length of a man’s arms around the object of his affections.”

Galley:

The kitchen of a ship. It is most likely a corruption of “gallery.” Ancient sailors cooked their meals on a brick or stone gallery laid amidships.

Head:

The bathroom aboard a naval ship. The term comes from the days of sailing ships when the place for the crew to relieve themselves was all the way forward on either side of the bowsprit, the part of the hull to which the figurehead was fastened.

Holystone:

A piece of sandstone used for scrubbing teak and other wooden decks. It was so nicknamed by an anonymous witty sailor because, as its use always brought a man to his knees, it must be holy!

Keelhauling:

A naval punishment. A rope was passed under the bottom of the ship, and the punishee was attached to it, sometimes with weights attached to his legs. He was dropped suddenly into the sea on one side, hauled underneath the ship, and hoisted up on the other. When he had caught his breath, the punishment was repeated.

Pea Coat:

A heavy topcoat worn in cold, miserable weather by seafaring men. Sailors who have to endure pea-soup weather often don their pea coats but the coat’s name isn’t derived from the weather. It was once tailored from pilot, or “P” cloth – a heavy, coarse, stout kind of twilled blue cloth. The garments made from it were called p-jackets or p-coats, later changed to pea jackets or peacoats.

Powder Monkey:

Boys or young teens who carried bags of gunpowder from the powder magazine in the ship’s hold to the gun crews aboard warships.

Scrimshaw:

Carved or incised intricate designs on whalebone or whale ivory.

Scuttlebutt:

Nautical parlance for gossip and rumour. In the navy, a water fountain is still called a “scuttlebutt,” from the days when crews got their drinking water from a “scuttled butt” – a wooden cask (butt) that had a hole punched in for the water to flow through. (Sinking a ship by punching in its hull is called scuttling.) As they waited for their turn for a drink, crew members chatted and exchanged news, just like people still do at an office water cooler or school drinking fountain.

Sextant:

A navigational instrument for determining latitude and longitude by measuring the angles of heavenly bodies in relation to the horizon.

S.O.S.:

Contrary to popular notions, the letters S.O.S. do not stand for “Save Our Ship” or “Save Our Souls.” They were selected to indicate distress because, in Morse code, these letters and their combination create an unmistakable sound pattern.

Starboard:

The right side of a ship. The Vikings called the side of a ship its board, and they placed the steering oar or “star” on the right side. Because the oar was on the right side, the ship was tied to the dock at the left side. This was known as the loading side, or “larboard.” Later, it was decided that “larboard” and “starboard” were too similar, especially when trying to be heard over the roar of a heavy sea, so larboard became the “side at which you tie up in port” or the “port” side.

Tar or Jack Tar:

A slang term for a sailor. Early sailors wore overalls and broad-brimmed hats made of tar-impregnated fabric called tarpaulin cloth. The hats, and the sailors who wore them, were called tarpaulins, which may have been shortened to tars.

Watches:

Divisions in a naval day. Traditionally, a 24-hour day is divided into seven watches. These are: midnight to 4 a.m., mid-watch; 4 to 8 a.m., morning watch; 8 a.m. to noon, forenoon watch; noon to 4 p.m., afternoon watch; 4 to 6 p.m., first dogwatch; 6 to 8 p.m., second dogwatch; and, 8 p.m. to midnight, evening watch. The half-hours of the watch are marked by striking the bell an appropriate number of times.