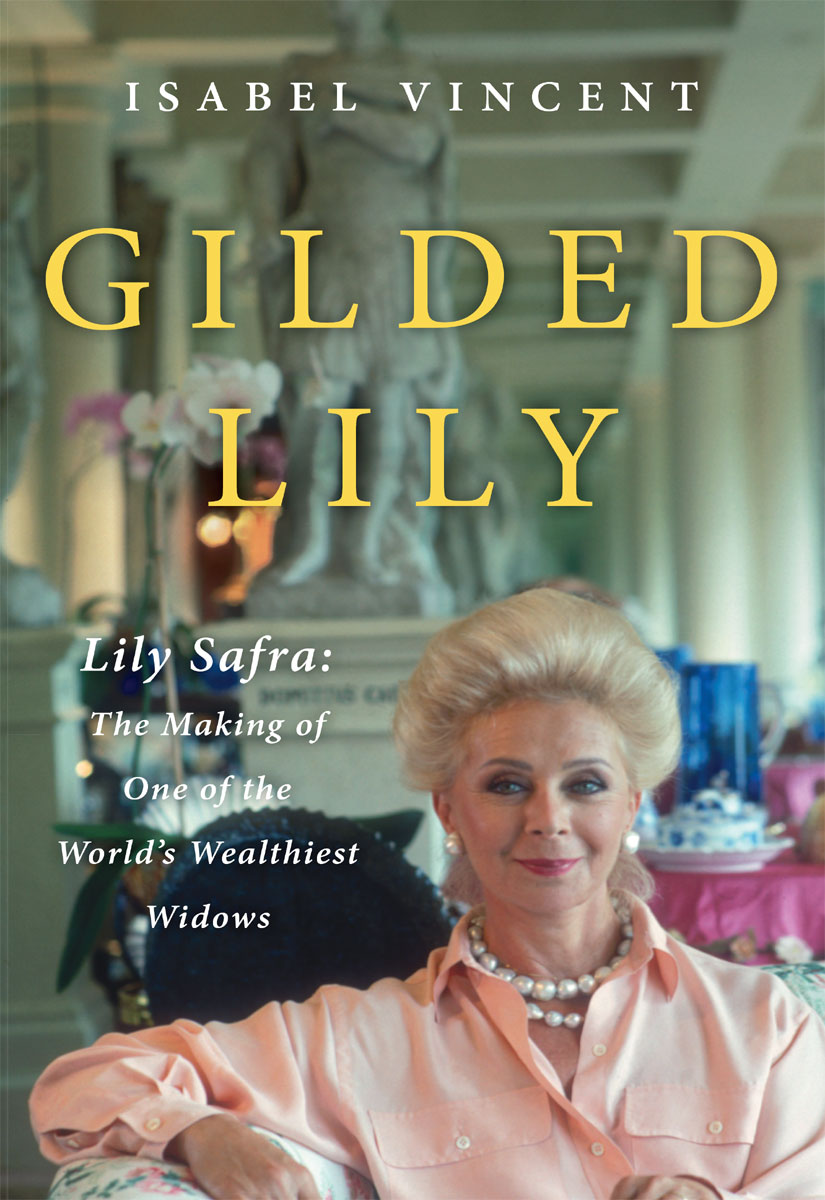

Gilded Lily

Authors: Isabel Vincent

Lily Safra: The Making of One of the World's Wealthiest Widows

In memory of my mother

“The Plot of a Great Novel”

“The Most Elegant Girl”

“Everything in Its Place”

“She Behaved Beautifully”

“Edmond Said He Would Fix Everything”

Two Weddings

“The Billionaires' Club”

“When I Give Lily a Dollar, Lily Spends Two Dollars”

“Not Our Fault”

“Years of Sorrow and Days of Despair”

“We Know Everything and We Know Nothing”

“The Plot of a Great Novel”

T

HE DRAMA THAT

would lead to the death of Edmond Safra began at 4:49 a.m. on Friday, December 3, 1999. That was when Patrick Picquenot, the night watchman at the Belle Epoque, first noticed the noise of the service elevator as it lumbered down from the fifth-floor back entrance to the banker's sumptuous duplex penthouse with its panoramic views of Monte Carlo. Moments later, the doors opened to reveal a man Picquenot had never seen before.

Perhaps he was a new member of Monsieur's staff?

It never occurred to the night watchman that the man might be an intruder because everyone who worked in the beaux-arts building on the avenue d'Ostende knew that Safra, one of the world's wealthiest bankers, was obsessed with security and had installed state-of-the-art alarm systems and steel doors and shutters in his residence above the Monaco branch of his Republic National Bank of New York, which was housed on the first floor of the Belle Epoque. The building also housed branches of Banque Paribas and Banque du Gothard. For all intents and purposes, the Safras' 10,000-square-foot penthouse, which contained two separate wings, was a bunker, impossible to penetrate.

The Safras also employed almost a dozen Mossad-trained security guards. Edmond himself suffered from a debilitating case of Parkinson's disease and was constantly attended by a team of well-trained

nurses. And even though he lived part of the year in Monacoâone of the safest places on earth, where there are myriad surveillance cameras monitoring the streets, one policeman for every 100 of its 30,000 residents, and two hundred identity checks carried out by the authorities every dayâEdmond refused to dispense with his extremely loyal security detail. But on that early Friday morning in December, not one of the members of his security staff was on duty at the apartment. They were all in Villefranche-sur-Mer, at the Safras' palatial summer home, which was a twenty-minute drive from Monaco.

Still, things were typically so quiet in Monaco that a lesser professional than Picquenot, a small, wiry man who was not armed, could probably be excused for nodding off on the job from time to time. In fact, Picquenot, who hailed from the sleepy town of Menton on the Italian border, was hard-pressed to remember a time when he had had to respond to any kind of robbery or break-in. He wasn't alone. A policeman who had spent twenty-two years on the Monaco force later confessed in court that he had never seen a gunshot wound. The only violence that he had witnessed, he said, involved an antiques dealer who attacked someone with a broken champagne bottle. Crime was rare in this luxe principality, known for its lavish casinos, Formula One racing, and generous tax breaks for its citizens, who are among the world's wealthiest people.

The truth is that Picquenot, at thirty-eight, had little experience when it came to dealing with any kind of violent emergency, which was why he was momentarily dazed when he saw the manâtall and lanky with dirty blond hair and a strange gleam in his piercing blue eyes. He hobbled out of the elevator doubled over in pain, his hands stained copper. He was shouting something in English, a language that Picquenot could barely understand. The man was clutching his stomach and limping, and blood, which appeared to be dripping from his stomach or his leg or both, was pooling on the Italian marble floor.

But Picquenot needed little translation to understand that something was terribly wrong at the Safra apartment. At first, he thought that the man had been shot, although he could not remember hearing anything resembling a gunshot in the moments before he appeared in the lobby. “I called the police,” recalled Picquenot. “A little later, a fire alarm went off on the west side. I called the fire brigade. Very rapidly, the police and fire services arrived.” But his recollection proved incorrect. There was no fire alarm until much later, a situation that was partly to blame for the chaos of that early winter morning in Monaco.

A few police officers reached the Belle Epoque at 5:12 a.m. and immediately began questioning the bleeding man, who Picquenot quickly found out was Ted Maher, an American and one of Edmond's nurses. Maher told the police officers that he had been the victim of two hooded intruders who had entered through an open window in Safra's penthouse. Before an ambulance arrived to take him to Princess Grace Hospital, the wild-eyed Maher, a former Green Beret with a sterling reputation as a neonatal nurse in New York, told police that the intruders were likely armed, and that Safra and another nurse, who huddled with the billionaire in his bunker-like bathroom, were in terrible danger. Maher was wincing in pain and bleeding profusely, and no one doubted his version of events. Not yet.

It was Maher's statements to police that would further contribute to the chaos of the next three hours and result in the horrible deaths of the sixty-seven-year-old billionaire banker and his night nurse Vivian Torrente, fifty-two. Perhaps, like Picquenot, police and firefighters in Monaco simply didn't have the experience of dealing with an emergency of this scale, so they took their time analyzing the situation, making sure that it was safe to send their own men to Safra's apartment to save the financier and put out the blaze that an hour later was still raging in Safra's bedroom.

They were careful to the point of stunning ineptitude, for when Safra's own chief of security showed up to help with the rescue op

eration, a police officer promptly arrested him and told him to get out of the way, even as he offered up the keys that would open the steel doors in the Safra apartment.

As the sun rose over Monaco, billows of black smoke began escaping through the roof of the Belle Epoque. Edmond and his nurse made frantic calls to police and family from the cell phone Maher had given to Torrente before he fled the apartment to alert authorities. Beginning at 5:00 a.m., Torrente would make six anguished phone calls to her boss, head nurse Sonia Casiano Herkrath, begging her to call police. Later, in her statements to police, Herkrath said she advised Torrente to place rolled-up wet towels around the room. Torrente told her that the bathroom was filling with black smoke, and that Safra stubbornly insisted they remain until he was certain that the police had apprehended the hooded intruders. Safra, a legendary banker to whom the world's wealthiest had entrusted their funds, had provided evidence for an FBI investigation into Russian money-laundering a year earlier. Since then, he had redoubled his security because he feared for his life.

“Enemies?” said his friend Marcelo Steinfeld. “Of course, Edmond had enemies. You don't get to make that much money and not have any enemies.”

Perhaps this explained why Safra huddled with his nurse in the bathroom, shaking uncontrollably in his yellow pajamas. He must have been terrified that these unnamed enemies, these shadowy “intruders,” had come to exact their revenge.

“Telephone calls between third parties and the occupants of the apartment, which was filled with smoke from the fire, apparently did not convince the occupants to let the firefighters in,” wrote the medical examiner who was assigned to carry out the autopsies hours later.

Edmond's first two calls were to his beloved wife, Lily, urging her to leave her apartment, which was across the hall on the sixth floor, and to get help immediately. Lily made a daring escape through her

bedroom window onto a balcony, and in a flowing nightgown with a navy school blazer that belonged to one of her grandsons draped over her thin shoulders, she appeared dazed and confused as she gingerly made her way down several flights of stairs to the lobby.

If Picquenot and the dozens of police officers who had by now assembled in the palatial lobby of the Belle Epoque noticed the rather frail and frightened banker's wife shivering in the ill-fitting blazer, few took any notice.

That would come later, after the funeral, and after the sale of her husband's bank to the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) made the front pages of the world's financial papers. Of course, the chatter among the aristocrats and the socialites who moved in the Safras' rarefied circles began soon after the media trucks pulled up outside the Belle Epoque to film the blaze and report live from Monaco on the bizarre series of events that would leave one of the world's richest bankers asphyxiated in his own home. By 6:15 a.m., many could clearly see the blaze from their own stately apartments along the avenue d'Ostende and avenue John F. Kennedy. A torrent of intercontinental phone calls began.

“As soon as I turned on the television and saw that the penthouse was on fire, the phone rang,” said one longtime resident of Monaco who could also see the Safras' burning penthouse from her own apartment. “The phone kept ringing with people calling me from London, New York, Paris, and Rio de Janeiro. Everyone wanted to know the same thing: âWhere is Lily?'”

Lily, one of the world's richest and most elegant women, was used to the chatter about herself. In many ways she courted it, propelling the media-shy Safra into society columns on three continents. Safra was her fourth husband, and her greatest catch, but he was less than enthusiastic about what seemed to be Lily's need to court publicity and appear at all the best parties.

“I saw their relationship as very unique,” said Eli Attia, who had worked as Safra's architect for nearly fifteen years, beginning in 1978.

“She gave him a new angle on life. He was very shy and not comfortable in his dealings with people. They were very complementary to each other and you can't escape [the fact] that it was a great love story.”

Safra, balding and stocky, with thick black eyebrows and sad eyes, moved slowly and deliberately. With his courtly Old World manner, he was in many ways the stereotype of the dark-suited prosperous banker, singularly devoted to his clients around the world. Lily once likened going to bed with him to attending a board meeting because “he would telephone his far-flung business associates all night.” Still, Safra was clearly in love with Lily, “a slim blonde charmer,” who was forty-two when they married in 1976. What she lacked in beauty in her later years, Lily made up for in elegance, sophistication, and extremely good taste. Safra, forty-four when he married her, was a legend in the banking community who was known for his sober discretion. The motto of his Republic National Bank in New York was “to protect not only your assets, but your privacy.”

“No other major banker since the era of the Morgans and Rockefellers has been so successful as an entrepreneur,” said

BusinessWeek

in a rare profile of Edmond Safra.

But the mighty banker allowed Lily to have her wayâmost of the time. Following their marriage, the couple regularly dined with such luminaries as Karl Lagerfeld, Valentino, and Nancy Reagan, and befriended

Women's Wear Daily

society columnist Aileen Mehle. One of the earliest mentions of Lily's entrée into Manhattan high society occurred in March 1981 at a dinner in the Safras' honor chez the Brazilian ambassador to the United Nations attended by Diana Vreeland, Bill Blass, the Safras' friends Ahmet and Mica Ertegun, and Nancy Reagan's “walker” and Manhattan society fixture Jerry Zipkin. “Lily answered a toast from her host with a sweet little speech, using one of the Plexiglas lorgnettes that Jerry Zipkin gives friends who are farsighted or nearing 40.” Lily was a few months shy of her forty-seventh birthday.

Later, Edmond and Lily attended the same benefits and luncheons as Elton John, Blaine and Robert Trump, and the Monegasque royals. Mehle wrote that Lily and her friend Lynn Wyatt, the Texas billionairess, were among a large entourage “tagging along” with Prince Albert of Monaco during his visit to New York in 1997.

Lily became such a luminary in haute circles in New York that her name became a boldface fixture alongside more established high-society icons. At a luncheon in New York in 1994, Lily must have been thrilled to be mentioned alongside Brooke Astor, the doyenne of the New York social world for decades and a paragon of East Coast old money. At the luncheon, Brooke Astor “wore her sable hat, and Lily Safra wore her velvet one.”

The Safras had “exquisite taste” and were considered important collectors. After Edmond's death, Lily sold their collection of eighteenth-century European furniture and decorative objects at a Sotheby's auctionâa two-day event in New York that raised a staggering $50 million, double the pre-auction estimate.

But the superlatives were saved for the Safras' magnificent homes around the world. A house Lily bought in London after Edmond's death was “perhaps the most beautiful home in all of London with a swimming pool on the ground floor, surrounded by what looks like the Garden of Eden.”

The jewel in the crown was surely their home in the south of Franceâa place

Women's Wear Daily

described as “one of the most wonderful private houses on the Cote d'Azur, maybe in the world.” Lily and Edmond threw fabled balls and “intimate dinners” at La Leopolda, the sprawling seaside villa, named for the estate's first owner, King Leopold II of Belgium. Invitations to the villa, which was surrounded by orange groves and stately cypresses, were the most sought-after among members of high society during the summer social season on the Riviera.

When

Women's Wear Daily

featured one of her most sumptuous balls at La Leopolda in August 1988âa vernissage of sorts after lav

ish renovationsâthe magazine referred to her as “The Gilded Lily” in the headline.

By the time Edmond died, Lily was well on her way to establishing her high-society bona fides. But even before she married Edmond, Lily had already honed her reputation as an elegant hostess. In South America, where she was only a minor fixture on the social circuit, first as the wife of a hosiery factory owner in Argentina and Uruguay, and then as the wife of one of Brazil's wealthiest men, friends remembered her for her acts of generosity and her sumptuous parties.

“Lily was an extremely generous woman, a great hostess, with elegant manners,” recalled Vera Contrucci Pinto Dias, who socialized with her in Rio de Janeiro in the 1960s. “She wasn't Princess Diana, but she was pretty close.”