Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (28 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

Lawrence Beesley

(photo credit 1.55)

The fact that the

Titanic

slowly resumed her course after hitting the iceberg is not included in many accounts of the disaster but it was noted by several others on board besides Lawrence Beesley. Quartermaster Alfred Olliver later testified that Captain Smith gave the “Half Speed Ahead” order for the engines not long after the collision. The captain had by then sent Fourth Officer Boxhall below on a tour of inspection, so it seems likely that he thought the ship would have to limp in to New York or Halifax under its own steam and that they could proceed slowly in the meantime. By best estimates, the ship moved forward for about ten minutes and may have stopped when Chief Officer Wilde reported to Smith that the forepeak tank, a water ballast tank deep in the forward bow, was taking in seawater.

Bruce Ismay had awakened in his deluxe B-deck suite not long after the collision and lay in bed wondering why the ship had stopped. His first thought was that they had dropped a propeller blade. Stepping into the hallway in his pajamas, he asked a steward, “

What has happened?” The steward replied that he did not know, so Ismay donned an overcoat and slippers and went up to the bridge.

“We have struck ice,” Smith explained.

“Do you think the ship is seriously damaged?” Ismay asked.

“I am afraid she is,” he replied.

Ismay returned to the grand staircase, where he met Chief Engineer Bell and asked him if he thought the damage was serious. Bell replied that it seemed to be so but that he thought the pumps would keep the ship afloat. Smith clearly believed this as well, since otherwise he would not have given the “Half Speed Ahead” order.

Just before midnight, Fourth Officer Boxhall returned to the bridge from his brief inspection down as far as F deck and told the captain he had seen nothing awry. Smith ordered him to find the ship’s carpenter so he could “sound” the vessel. Boxhall was on the stairs to A deck when he met the carpenter coming up. “

The ship is making water,” he reported breathlessly. Boxhall asked him to report this to the captain and continued down the staircase until he met a mail clerk, who announced, “The mail hold is filling rapidly.”

“You go and tell the captain and I will go down and see,” Boxhall replied.

When the fourth officer entered the post office on G deck, the mail clerks were hastily pulling armfuls of envelopes out of the sorting racks. On looking down into the lower storage room, he saw mailbags floating in water. When Boxhall reported this to the bridge, the captain gave the order for the lifeboats to be uncovered and went below to see the damage for himself. The ship’s designer,

Thomas Andrews, was already making his own inspection tour of the lower decks. He went into the post office and soon dispatched a mail clerk to find the captain. The clerk hurried along the corridor and returned with Captain Smith and Purser McElroy. After they had viewed the damage, Andrews was overheard saying to Smith, “Well, three have gone already, Captain.” Andrews was undoubtedly referring to three of the ship’s bulkheads that divided the ship into the watertight compartments that gave the

Titanic

its reputation for unsinkability. With only three compartments flooded, however, there was a chance that the pumps could stay ahead of it. The captain then returned to the bridge and gave the order for women and children to go up on deck with lifebelts. Thomas Andrews, meanwhile, continued his inspection.

At around twelve-twenty-five William Sloper saw Andrews racing up the staircase with a deeply worried look on his face. As the ship’s designer passed by Dorothy Gibson, she put her hand on his arm and asked him what had happened. Andrews simply brushed past the prettiest girl and continued upward three stairs at a time. He had just discovered that two more watertight compartments had been breached. Andrews knew how serious this was. The bulkhead between the fifth and sixth compartments extended only as high as E deck. As the ship was pulled down at the bow, the water would spill over it into the next compartment, and then the next, until the ship inevitably sank. In all his planning at Harland and Wolff, he had never imagined a scenario such as this. Andrews informed the captain that the ship had only an hour left to live—an hour and a half at best. Smith immediately told Fourth Officer Boxhall to calculate the liner’s position and take it to the Marconi Room so the call for assistance could be sent out. He also gave orders to muster the passengers and crew.

Only moments after Andrews had rushed by him and Dorothy Gibson, William Sloper heard a steward announce, “

The captain says that all passengers will dress themselves warmly, bring their life preservers and go up to the top deck.” He arranged to meet Dorothy and her mother shortly and returned to his cabin. Having pulled down his lifebelt from an overhead rack, he then went back into the hallway, and there a voice from a nearby cabin called out, “

What has happened?” It was the sickly Hugo Ross, one of the trio of Canadian bachelors that Sloper had dubbed “the Three Musketeers” on the

Franconia

. He went into Ross’s room and tried to reassure him by saying he didn’t think the ship was in serious difficulties. Ross had already been told about the iceberg by Major Peuchen, who had visited him shortly after the collision.

At eleven-forty Peuchen had been preparing for bed when he felt the ship quiver from what he thought was a heavy wave. After going up to A deck and spying ice lying along the railing in the well deck, he had decided to inform Hugo Ross, who reportedly said to him, “

It will take more than an iceberg to get me out of my bed.” The major then knocked on Harry Molson’s door but found him out. Peuchen soon saw another Canadian acquaintance, Charles Hays, walking with his son-in-law on C deck and asked him if he had seen the ice. Hays replied that he had not, so Peuchen took the two men up to the A-deck promenade to show it to them. There he noticed a change from his last visit. “Why, she is listing,” he said to Hays. “She should not do that, the water is perfectly calm and the boat has stopped.” The railroad president was dismissive. “You can’t sink this boat,” he replied. “No matter what we’ve struck, she is good for eight or ten hours.”

Archibald Gracie was also on the promenade deck at around this time but did not sense any listing. He had awakened after the collision to the sound of steam being vented and had decided to investigate. Gracie went up first to the boat deck, which he found deserted, and then down to A deck, where he peered over the rail and saw nothing unusual. On returning to the staircase, he spotted Bruce Ismay hurrying upward with a crewman. Ismay was by then wearing a business suit, and Gracie thought he looked preoccupied but not alarmed. Gracie then ran into his friend James Clinch Smith and a few other passengers by the staircase landing on B deck.

Smith opened his hand to reveal a piece of ice that was flat and slightly rounded, like a pocket watch, and wryly suggested that Gracie might want to take it home as a souvenir. He also told Gracie what he knew about the collision and reported that someone who had rushed out from the smoking room to see the berg claimed that it had towered above A deck. Gracie also heard about the postal clerks dragging mailbags out of the storage room. Soon there was a noticeable list in the floor of the staircase landing, and Gracie and Smith decided to go back to their staterooms and meet later.

Major Peuchen was standing near the A-deck staircase foyer at approximately twelve-twenty-five, when a group of grim-faced people came down from the boat deck, Thomson Beattie of “the Musketeers” among them. “

The order is for lifebelts and boats,” Beattie reported. Peuchen was taken aback. “Will you tell Hugo Ross?” he asked. Beattie replied that he would. Peuchen then returned to his cabin on C deck and began to change out of his evening clothes. After donning heavy underwear, two pairs of socks, and a warm sweater, he put on his overcoat and a life preserver. As he left his small cabin, he glanced at a tin box that contained some jewelry and $217,000 worth of stocks and bonds. This was no time to bother with valuables, he decided, and stepped outside. The corridor was filled with passengers in lifejackets, and a few of the women were weeping. Some wore only dressing gowns or kimonos and were advised to go and dress more warmly. Peuchen, too, turned around and went back into his room. He retrieved his favorite pearl tiepin, pocketed three oranges, and returned to the staircase.

No one had to tell Margaret Brown to dress warmly. After hearing about the order for lifebelts, she had pulled on several pairs of woolen stockings under a black velvet suit with white silk lapels, placed a silk cap on her head, and wrapped herself in sable furs. She found two lifebelts in her cabin and decided to carry both. Before leaving her stateroom, she retrieved the small turquoise tomb figure she had bought in Egypt for good luck and tucked it into her pocket. When she reached the staircase foyer on A deck, her traveling companion Emma Bucknell came toward her. “Didn’t I tell you something was going to happen?” she whispered nervously, recalling their conversation on the

Nomadic

.

Edith Rosenbaum, who had had similar premonitions on the tender, was now surprisingly calm. She had gone up to the boat deck before midnight and seen the ice fragments in the well deck but when told that there was nothing to worry about, had returned to her cabin. As she was about to get back into bed, a crewman knocked on her door and announced that all passengers were required to put on lifebelts.

“

What for?” Edith asked.

“That is an order,” he replied and moved on.

Edith packed up her clothes and jewelry and tidied her room to leave it looking presentable. She locked all her trunks, closed the curtains, put on a warm fur coat, and left the cabin without taking her lifebelt. On meeting her room steward, Robert Wareham, she asked him if he thought there was really any danger or if the order for lifebelts was just following regulations. The steward replied that the orders were for lifebelts and lifeboats but that he expected the ship would be towed to Halifax. Edith pulled out the keys to her trunks and gave them to Wareham, asking him to clear them at customs there for her.

“Well, if I were you, I would kiss those trunks good-bye,” he replied.

“Do you think the boat is going to sink?” Edith asked, slightly startled.

“No one thinks anything, we hope,” the steward responded more circumspectly.

On her way to the lounge, Edith passed the open cabin door of a shipboard acquaintance named Robert Daniel, a young banker from an old Virginia family. Daniel had purchased a French bulldog in England named Gamin de Pycombe and Edith found it whimpering in the stateroom. She tucked the dog under the bedcovers, patted its head, and left.

Norris Williams and his father had also decided to go up on deck after being awakened by the collision, and they, too, had observed the ship slowly gliding forward at half speed. After returning to their room to don their fur coats and lifebelts, they found a steward trying to open a jammed cabin door on C deck. Over objections from the steward, Norris put his shoulder to the door and broke it open—to the relief of the man inside. As he walked away, Norris heard the steward call out, “

I will be forced to report you for having damaged company property!”

Sometime after twelve-thirty, steerage passenger Daniel Buckley watched as a man kicked at a locked iron gate at the top of a forward stairway. The gate had been unlocked earlier when Buckley had

gone through it up to B deck. There he’d seen first-class passengers tying on their lifebelts and decided he’d better return for his. Pushing his way down through a stream of third-class passengers surging upward, Buckley arrived at the corridor to his cabin only to find it under water. As he climbed back up the stairway to B deck Buckley heard a commotion as a crewman pushed a man from steerage back down the stairs and locked the gate, barring the way to the first-class deck. The furious steerage passenger picked himself up, smashed through the locked gate, and raced off in pursuit of the crewman. He later told Buckley he would have thrown the sailor into the ocean if he had caught him.

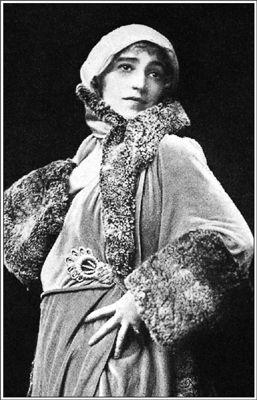

Edith Rosenbaum

(photo credit 1.77)

Thomas Andrews, meanwhile, circulated along the first-class hallways making sure that the stewards were getting passengers out of their staterooms. He saw stewardess May Sloan, whom he knew from Belfast, knocking on doors and told her to make sure that all passengers put on their lifebelts, adding that she should find one for herself and get up on deck soon. His face, she thought, “

had a look as though he were heart broken.”

At around twelve-thirty-five, William Sloper rejoined his bridge companions, Dorothy Gibson, her mother, and Frederic Seward, on the A-deck staircase foyer. The foursome walked up to the boat deck past the elegant wall clock set into a carved relief of Honor and Glory crowning Time. On the chilly boat deck they were greeted by the deafening roar of steam being vented through pipes that ran up the sides of the three forward funnels. The noise made conversation impossible—it even made it difficult for operator Jack Phillips in the Marconi Room to hear replies to his calls for assistance.