Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (3 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

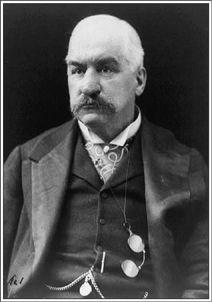

J. Pierpont Morgan

(photo credit 1.32)

The brilliant showcasing of American paintings and sculpture at the Chicago exposition spurred the idea of creating an academy in Rome where American artists could soak up classical inspiration. Charles F. McKim, one of the partners in the famed architectural firm McKim, Mead and White, spearheaded the academy project, and Frank Millet agreed to be the secretary of its first board. With all the funds for the American Academy having to be privately raised, McKim sought out the greatest moneyman of the age, J. Pierpont Morgan. On March 27, 1902, McKim breakfasted with the financier at his home at 219 Madison Avenue and came away with more than he had expected. Morgan had agreed to give financial support to the American Academy but had also asked McKim to draft plans for a private library to house his collection of rare books and manuscripts on land next to his Madison Avenue brownstone. “

I want a gem,” Morgan declared, and McKim’s Italian Renaissance design for the Morgan Library still stands as one of New York’s architectural treasures.

J. P. Morgan traveled and acquired for his collections constantly, but at sixty-five showed no signs of lessening his business interests. “

Pierpont Morgan … is carrying loads that stagger the strongest nerves,” wrote Washington diarist Henry Adams in April of 1902. “Everyone asks what would happen if some morning he woke up dead.” Among Morgan’s many “loads” at the time was a scheme to create a huge international shipping syndicate that could stabilize trade and yield huge returns from the lucrative transatlantic routes. By June of 1902 he had purchased Britain’s prestigious White Star Line for $32 million and combined it with other shipping acquisitions to form a trust called the International Mercantile Marine. In 1904 Morgan installed White Star Line’s largest shareholder, forty-one-year-old J. Bruce Ismay, son of the line’s late founder, as president of the IMM. The second-largest shareholder was Lord William J. Pirrie, the chairman of Harland and Wolff, the Belfast shipbuilders responsible for the construction of White Star’s ships. Pirrie had been the chief negotiator with Morgan’s men and was placed on the board of the new trust.

The British government had acceded to Morgan’s flexing of American financial muscle in the acquisition of White Star but had also provided loans and subsidies to the rival Cunard Line for the building of the world’s largest, fastest liners,

Lusitania

and

Mauretania

—with the proviso that they be available for wartime service. By the summer of 1907, the

Lusitania

had made its record-breaking maiden voyage, and Pirrie and Ismay soon hatched White Star’s response. They would use Morgan’s money to build three of the world’s biggest and most luxurious liners. Within a year Harland and Wolff had drawn up plans for two giant ships, and by mid-December the keel plate for the first liner, the

Olympic

, had been laid. On March 31, 1909, the same was done for a sister ship, to be called

Titanic

. A third, initially named

Gigantic

, was to be built later.

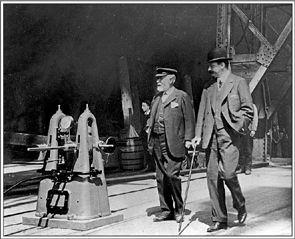

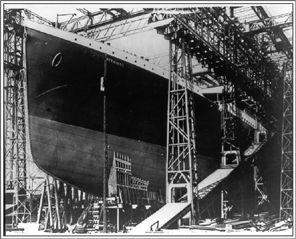

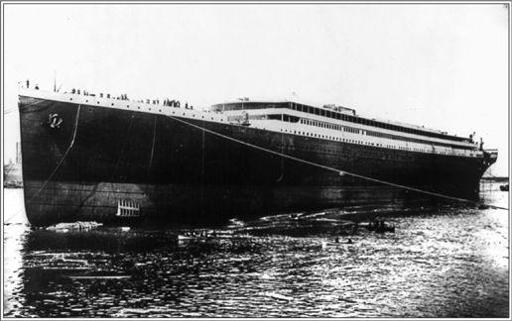

Lord Pirrie (top, at left) and J. Bruce Ismay inspect the

Titanic

in the Harland and Wolff shipyard (middle) before her launch on May 31, 1911 (above).

(photo credit 1.33)

There is a now-famous photograph of J. Bruce Ismay walking with Lord Pirrie beside the massive hull of the

Titanic

shortly before its launch on May 31, 1911. The tall, mustachioed Ismay, sporting a bowler hat and a stylish walking stick, towers over the white-whiskered Pirrie, who wears a jaunty, nautical cap. Missing from the photo is J. P. Morgan, who had traveled to Belfast with Ismay and would shortly join him and other dignitaries on a crimson-and-white-draped grandstand. To the crowd of more than a thousand onlookers, Morgan would have been instantly recognizable from countless newspaper cartoons depicting him as the archetypal American moneybags—his walrus mustache and giant purple bulb of a nose, the product of a skin condition called rhinophyma, being easily caricatured.

For the launch ceremony, there was no beribboned champagne bottle to smash against the bow and no titled dowager to pronounce “I name this ship

Titanic

.” That was not how White Star did things. Instead, at five minutes past noon, a rocket was fired into the air, followed by two others, and then the nearly 26,000-ton hull began to slide into the River Lagan to cheers and the blowing of tug whistles. A white film from the tons of tallow, train oil, and soap used to grease its passage spread over the water as the ship was brought to a halt by anchor chains. Soon, the

Titanic

’s hull gently rocked in the river while the newly completed

Olympic

waited nearby.

The launch had gone off just as planned and a highly pleased Lord Pirrie hosted a luncheon for Morgan, Ismay, and a select list of guests in the shipyard’s offices, while several hundred more were entertained at Belfast’s Grand Central Hotel, where a third luncheon was held for the gentlemen of the press. During the speeches at the press luncheon, the construction of the “leviathans,”

Olympic

and

Titanic

, was hailed as a “

pre-eminent example of the vitality and the progressive instincts of the Anglo-Saxon race.” That American money had paid for them was made a positive by the observation that “the mighty Republic in the West” and the United Kingdom were both Anglo-Saxon nations that had become more closely united as a result of their cooperation. While the Belfast men toasted their success and the primacy of their race, a shipyard worker named James Dobbins lay in hospital, his leg having been pinned beneath one of the wooden supports for the hull during the launch. Dobbins would die from his injuries the next day.

Following the luncheon, J. P. Morgan and Bruce Ismay boarded the

Olympic

along with other guests and sailed for Liverpool. Exactly seven months later, on December 31, 1911, Morgan would walk up the

Olympic

’s gangway once again, this time in New York bound for Southampton. From England he went on to Egypt, where he spent the winter at a desert oasis called Khargeh supervising the excavation of Roman ruins and an early Christian cemetery. By mid-March, Morgan was in Rome, and on the morning of April 3, 1912, he stood with Frank Millet atop the Janiculum Hill, reviewing the plans and site for the new American Academy building. Like the Morgan Library, this was to be another of Charles McKim’s Italian Renaissance palaces, built from a design drawn up by the architect before his death in 1909. Millet was keen to see McKim’s dream realized and Morgan told the

New York Times

, “

I hope that here will eventually be an American institution of art, greater than those of the other countries, which are already famous.” The next day the financier went on to Florence, where Millet soon joined him, perhaps to lend an informed opinion on Morgan’s ceaseless acquiring of art and antiquities. “

Pierpont will buy anything from a pyramid to a tooth of Mary Magdalene,” his wife had once noted. Morgan was no doubt pleased that Millet was sailing on the maiden voyage of the

Titanic

. He had planned to be on board himself before changing his plans in favor of a stay at a spa at Aix-les-Bains with his mistress.

WHILE MORGAN TOOK

the waters in Aix on April 10, Millet waited on the Normandy coast for Morgan’s newest ship to arrive. Eschewing the loud Americans crowding the waiting room, he may have chosen to stretch his legs after the long train ride from Paris. In front of the small, Mansard-roofed Gare Maritime stood the White Star tenders,

Traffic

and

Nomadic

, on which luggage and mail sacks were being loaded. The two tenders had been built at Harland and Wolff to service the new

Olympic

-class liners which were too large to dock in Cherbourg, the first stop after Southampton on White Star’s transatlantic route. The quay in front of the Gare Maritime led to a long jetty with an ancient stone tower at its end. It was a mild spring day with scudding clouds allowing bursts of sunshine, so Frank might have walked out on the jetty to see if there was any sign of the liner on the horizon. The walk would have helped to clear his mind of the institutional politics that had plagued him in Rome. As he wrote to Alfred Parsons the next day: “

If this sort of thing goes on I shall chuck it. I won’t lose my time and my temper too.”

It would be a big disappointment for Lily Millet if Frank chose to “chuck” his post as head of the American Academy. She was enchanted with the Villa Aurelia, the ochre seventeenth-century cardinal’s palace that went with the job. Now that her children were grown, Lily was establishing a career as an interior designer and had great plans for the villa and its gardens with their sweeping views of Rome. Here she could imagine the serene evenings of their twilight years, reconciled and reunited with her wandering husband.

Frank’s friend Archie Butt, too, had admired the villa when the two men had stayed there together before Lily arrived. Since 1910, Frank’s more-or-less permanent base had been Washington, D.C., where he had shared a house with Major Archibald Willingham Butt, the president’s military aide, known to all as “Archie.” It was Frank who had persuaded an exhausted Archie to come with him to Rome the month before and take some rest-and-recovery time before the fall presidential election. President Taft needed his closest aide to be in fighting trim for the coming campaign, and had arranged letters of introduction for Archie to the pope and the king of Italy to grant an air of officialdom to his trip. According to a March 31 social column in the

New York Times

, Major Butt had “

had the entrée to every house worth while in Rome,” and “by doing exactly what the doctors forbade,” as Archie himself had put it, he was in splendid condition and ready to return home. Major Butt had gone on to visit embassies in Berlin and Paris before continuing to England to see his brother. At about the same time that Frank was departing from Paris on the

Train Transatlantique

, Archie had boarded the Boat Train at London’s Waterloo Station for the noontime departure of the

Titanic

from Southampton.