Gimme Something Better (52 page)

Read Gimme Something Better Online

Authors: Jack Boulware

Tim was just a character. He has a very slow personality at first, where he just speaks really slow, kinda slang, like he’s trying to be ghetto. But then you realize that he’s always like that. It’s just his personality. He looked like a punk rocker. Because of what I thought at the time a punk rocker was. He always liked to have droopy pants, belts and things falling off of him.

Matt always talked like he was in his 30s, like he’d experienced life way more than everybody else. He had a way of talking like he was a stand-up comedian. Telling you how life is hard and how he’s experienced a lot. He was maybe 21 at the time. But he had confidence about him, and that I was really drawn to. I was an alright drummer, but he taught me a couple tricks on how to play with a bass player. And that’s what I needed.

I met Jesse a couple weeks later. He was a really good guy, but a little more withdrawn. I didn’t really know what to think of him. Honest and sometimes hard to deal with, but very creative. We all got together, and I knew that was gonna be a creative band. At the time I was extremely shy. I really felt that driving force of Tim and Jesse, and wanted to see where that was gonna go.

Matt Freeman:

We played our first show in Dave’s garage.

We played our first show in Dave’s garage.

Tim Armstrong:

Then the next one was with MDC at Gilman Street. It took us two months to get a set together.

Then the next one was with MDC at Gilman Street. It took us two months to get a set together.

Dave Mello:

We all liked catchy songs. We all liked the Clash. We were really young, and all four of us liked to go crazy onstage. I was really shy at first, but the energy that they had—especially Tim, who loves to run around with his guitar onstage and still stay on time. I really dug that. I would do the same thing.

We all liked catchy songs. We all liked the Clash. We were really young, and all four of us liked to go crazy onstage. I was really shy at first, but the energy that they had—especially Tim, who loves to run around with his guitar onstage and still stay on time. I really dug that. I would do the same thing.

Jeff Ott:

Jesse, cute guy, Tim, cute guy. That was a lot of the immediacy of success. I don’t want to sound derogatory about either Rancid or about Jesse’s bands. But for me personally, the thing about that band was Tim and Matt writing the music, and Jesse writing the lyrics. Each half was perfect in its own right.

Jesse, cute guy, Tim, cute guy. That was a lot of the immediacy of success. I don’t want to sound derogatory about either Rancid or about Jesse’s bands. But for me personally, the thing about that band was Tim and Matt writing the music, and Jesse writing the lyrics. Each half was perfect in its own right.

Dave Mello:

It was a lot about playing weekend parties. At such and such house, Eggplant’s house, my garage. It was all these people from Gilman becoming friends and saying, why don’t we just have shows every weekend? If it’s not a show here, it could be a barbeque or picnic here or a party. We played with Crimpshrine all the time.

It was a lot about playing weekend parties. At such and such house, Eggplant’s house, my garage. It was all these people from Gilman becoming friends and saying, why don’t we just have shows every weekend? If it’s not a show here, it could be a barbeque or picnic here or a party. We played with Crimpshrine all the time.

Jesse Michaels:

A lot of young kids were doing very spontaneous obscure little things in backyards and basements. So it was a perfect time to have a real sneaky little underground thing going.

A lot of young kids were doing very spontaneous obscure little things in backyards and basements. So it was a perfect time to have a real sneaky little underground thing going.

Gavin MacArthur:

My band in high school opened for Op Ivy at the Albany Rec Center, across the street from both the Mellos’ and my parents’ house. As soon as Op Ivy showed up, the place just filled up with all these punks. The place went totally crazy. It was super energetic. I’d listened to a few ska things, and of course I listened to punk. That was the first band I heard that combined the two.

My band in high school opened for Op Ivy at the Albany Rec Center, across the street from both the Mellos’ and my parents’ house. As soon as Op Ivy showed up, the place just filled up with all these punks. The place went totally crazy. It was super energetic. I’d listened to a few ska things, and of course I listened to punk. That was the first band I heard that combined the two.

Jesse Michaels:

We played all over the place. Berkeley, Oakland, El Cerrito, Alameda, San Jose, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Pinole, Benicia. If you took a map and drew a 50-mile perimeter around Berkeley, we played within that.

We played all over the place. Berkeley, Oakland, El Cerrito, Alameda, San Jose, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Pinole, Benicia. If you took a map and drew a 50-mile perimeter around Berkeley, we played within that.

Matt Freeman:

We’d go wherever. “Oh, you’re having a party up in Lake County near Healdsburg?” We’d go up there.

We’d go wherever. “Oh, you’re having a party up in Lake County near Healdsburg?” We’d go up there.

Tim Armstrong:

We also played the Albany Laundromat. Wherever we could.

We also played the Albany Laundromat. Wherever we could.

Matt Freeman:

Gilman Street would have all these bands, and Operation Ivy would be at the bottom, always. They’d say, “You gotta play last,” because they didn’t want people to leave.

Gilman Street would have all these bands, and Operation Ivy would be at the bottom, always. They’d say, “You gotta play last,” because they didn’t want people to leave.

Jesse Michaels:

I think we wore the place out a little bit. We’d play there like twice a month. Less than a year into it, we recorded some songs for the

Turn It Around

compilation. I wondered if we were ready. But Matt and Tim are just a machine, they never stop. And of course they were right, you have to strike while the iron’s hot. So we recorded two songs. And did a 7-inch I think within six months after that. We were playing constantly.

I think we wore the place out a little bit. We’d play there like twice a month. Less than a year into it, we recorded some songs for the

Turn It Around

compilation. I wondered if we were ready. But Matt and Tim are just a machine, they never stop. And of course they were right, you have to strike while the iron’s hot. So we recorded two songs. And did a 7-inch I think within six months after that. We were playing constantly.

Tim Armstrong:

Lookout! wasn’t even a label yet. Then ’88,

Hectic

came out. I was skeptical we were gonna sell out the first pressing. But Larry always knew that the shit was important. He would tell us that, and we would be like, “Oh, dude, shut up.”

Lookout! wasn’t even a label yet. Then ’88,

Hectic

came out. I was skeptical we were gonna sell out the first pressing. But Larry always knew that the shit was important. He would tell us that, and we would be like, “Oh, dude, shut up.”

Murray Bowles:

It was a really phenomenal scene. When Op Ivy first started playing there would be 20 or 30 people, and all of a sudden the shows would be packed. Nobody had heard of speed ska before.

It was a really phenomenal scene. When Op Ivy first started playing there would be 20 or 30 people, and all of a sudden the shows would be packed. Nobody had heard of speed ska before.

Billie Joe Armstrong:

People from Danville started flocking over to come see ’em play. I loved ’em, I thought they were the best.

People from Danville started flocking over to come see ’em play. I loved ’em, I thought they were the best.

Jason Lockwood:

They were playing at Gilman, I got there and saw my friends up there making great music. In between sets I climbed over all the kids and got up in Tim’s face and was like, “This is fantastic! I thought you guys were gonna suck so bad, and you’re great!”

They were playing at Gilman, I got there and saw my friends up there making great music. In between sets I climbed over all the kids and got up in Tim’s face and was like, “This is fantastic! I thought you guys were gonna suck so bad, and you’re great!”

Larry Livermore:

They were very good musicians. Matt’s one of the most amazing bass players in the world. Tim’s a very interesting guy, and a very intelligent guy. But he’s also got a persona that some people find it hard to get through. I don’t have any great difficulty talking with him. But some people do. I think he puts it up as a little bit of a barrier. ’Cause he’s very much a self-made man. I don’t know what Jesse’s like now. But in his heyday, he had the room in the palm of his hand.

They were very good musicians. Matt’s one of the most amazing bass players in the world. Tim’s a very interesting guy, and a very intelligent guy. But he’s also got a persona that some people find it hard to get through. I don’t have any great difficulty talking with him. But some people do. I think he puts it up as a little bit of a barrier. ’Cause he’s very much a self-made man. I don’t know what Jesse’s like now. But in his heyday, he had the room in the palm of his hand.

Anna Brown:

The first time you saw them it was just really clear that they were totally special. There were whole groups of people dancing to really good lyrics about things. Deep but catchy. They weren’t ever sappy.

The first time you saw them it was just really clear that they were totally special. There were whole groups of people dancing to really good lyrics about things. Deep but catchy. They weren’t ever sappy.

Sham Saenz:

Gilman had this battle of the bands one time and it was Green Day, El Vez, Crimpshrine, Operation Ivy. Operation Ivy got up and did a cover of Journey’s “When the Lights Go Down in the City” and it was the most amazing thing on earth. It was funny and clever and executed super well and I was like, “Okay, these Gilman guys are doing their own fuckin’ thing.”

Gilman had this battle of the bands one time and it was Green Day, El Vez, Crimpshrine, Operation Ivy. Operation Ivy got up and did a cover of Journey’s “When the Lights Go Down in the City” and it was the most amazing thing on earth. It was funny and clever and executed super well and I was like, “Okay, these Gilman guys are doing their own fuckin’ thing.”

Jesse Michaels:

It’s hard to talk about because we were very lucky. I don’t want to sound like I’m blowing our horn or anything. But we generally won crowds over because we really brought a lot of energy. Every night, no matter how small the crowd was. People dug that. Also a lot of people had never heard the ska thing. We hit ’em with a gimmick right away and they liked that, too.

It’s hard to talk about because we were very lucky. I don’t want to sound like I’m blowing our horn or anything. But we generally won crowds over because we really brought a lot of energy. Every night, no matter how small the crowd was. People dug that. Also a lot of people had never heard the ska thing. We hit ’em with a gimmick right away and they liked that, too.

Tim Armstrong:

After we made our first CD, Christmastime 1988, in our house on Pierce Street, my whole family was there. My uncle from Florida, who’s just this bombastic character, in front of everybody, he was like, “Tim!” Room got quiet. “So Tim, when you gonna find your niche in life? Everyone in here has a niche. What’s your niche? You need a niche.” And my poor mom, “Oh, no, here he goes.” I said, “If anybody in this family has a fuckin’ niche”—the room got dead quiet, I was lookin’ at everybody—“it’s fuckin’ me. I’m in Operation Ivy, I made a record. All I want to do is make a record and be in a band and be a part of somethin’, and I did it! So if anybody in this family has a fuckin’ niche, it’s me!”

After we made our first CD, Christmastime 1988, in our house on Pierce Street, my whole family was there. My uncle from Florida, who’s just this bombastic character, in front of everybody, he was like, “Tim!” Room got quiet. “So Tim, when you gonna find your niche in life? Everyone in here has a niche. What’s your niche? You need a niche.” And my poor mom, “Oh, no, here he goes.” I said, “If anybody in this family has a fuckin’ niche”—the room got dead quiet, I was lookin’ at everybody—“it’s fuckin’ me. I’m in Operation Ivy, I made a record. All I want to do is make a record and be in a band and be a part of somethin’, and I did it! So if anybody in this family has a fuckin’ niche, it’s me!”

That’s almost 20 years ago. I was in Operation Ivy at the right time. It’s weird, I can’t even intellectualize—maybe it doesn’t come across—but I always felt like I made it back then. I tried to tell my uncle that. He don’t really want to talk to me too much about anything, really.

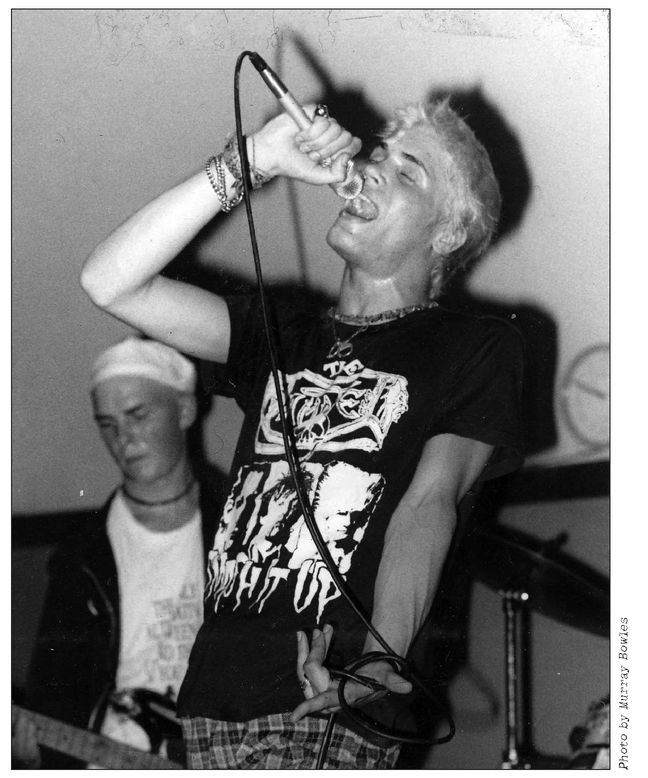

Bombshell: Lint and Jesse Michaels of Op Ivy

Jesse Michaels:

Before I was in a band, I was into stuff like the Bad Brains, Crucifix, Jerry’s Kids, and Minor Threat and MDC and BGK and Marginal Man. Generally with hardcore, it was all political back then. It was even political when it probably shouldn’t have been. Some people had no idea what they were talking about. But I was in that consciousness and did what I knew. The world was an extremely fucked-up place, and you should talk about it with music. That was a natural thing to communicate, especially punk music because it takes basically a rebel standpoint. If you’re gonna be rebellious, what are you thinking? Do you have ideas, or is it just a fashion?

Before I was in a band, I was into stuff like the Bad Brains, Crucifix, Jerry’s Kids, and Minor Threat and MDC and BGK and Marginal Man. Generally with hardcore, it was all political back then. It was even political when it probably shouldn’t have been. Some people had no idea what they were talking about. But I was in that consciousness and did what I knew. The world was an extremely fucked-up place, and you should talk about it with music. That was a natural thing to communicate, especially punk music because it takes basically a rebel standpoint. If you’re gonna be rebellious, what are you thinking? Do you have ideas, or is it just a fashion?

Sham Saenz:

We all knew something big was going to happen when Operation Ivy played the anti-Apartheid riots. There was a huge sit-in at Sproul Plaza up on Telegraph. Everybody was up there protesting, and they had this day show. I sat on this balcony not really giving too much of a shit about Operation Ivy. I had dreadlocks but I was more peace-punky. I looked down and they started to play, and the crowd accumulated, and then it kept accumulating. And then it seemed like as far as you could look there was people watching them and knew the words. I was just going, wow, people like these guys.

We all knew something big was going to happen when Operation Ivy played the anti-Apartheid riots. There was a huge sit-in at Sproul Plaza up on Telegraph. Everybody was up there protesting, and they had this day show. I sat on this balcony not really giving too much of a shit about Operation Ivy. I had dreadlocks but I was more peace-punky. I looked down and they started to play, and the crowd accumulated, and then it kept accumulating. And then it seemed like as far as you could look there was people watching them and knew the words. I was just going, wow, people like these guys.

Noah Landis:

Back then, things like the Specials were what everyone played at high school parties. They tapped into a little bit of that energy and incorporated it with the new punk rock East Bay thing that was happening.

Back then, things like the Specials were what everyone played at high school parties. They tapped into a little bit of that energy and incorporated it with the new punk rock East Bay thing that was happening.

Jesse Michaels:

Part of what we were trying to do was the positive energy thing. To bring a hardcore intensity with less negativity. It was still dark but it wasn’t like Condemned to Death or Flipper. It had a couple more colors in the spectrum.

Part of what we were trying to do was the positive energy thing. To bring a hardcore intensity with less negativity. It was still dark but it wasn’t like Condemned to Death or Flipper. It had a couple more colors in the spectrum.

Anna Brown:

Jesse was a great front person. He just would bounce off the walls the whole time.

Jesse was a great front person. He just would bounce off the walls the whole time.

Billie Joe Armstrong:

I really looked up to him. He was like a hero because he wrote amazing lyrics and was a great artist and had this great punk sensibility. But he was also an incredibly kind person, just really sweet. He took real interest in what people had to say. In what I had to say.

I really looked up to him. He was like a hero because he wrote amazing lyrics and was a great artist and had this great punk sensibility. But he was also an incredibly kind person, just really sweet. He took real interest in what people had to say. In what I had to say.

Martin Brohm:

Everybody knew the words. Seven people wrapped around the mic with Jesse. Everybody was singing except for us. We were telling them to fuck off. We had a bit of banter going back and forth, with Isocracy and Op Ivy. Some people liked it and some people didn’t. We would have fake fights where we’d jump onstage and fight with ’em. It went over good with Jesse. Matt was good with it. Tim didn’t like it at all. Lenny didn’t like it at all. But in between songs we would be screamin’ and yellin’: “You guys fuckin’ suck! Fuck you!”

Everybody knew the words. Seven people wrapped around the mic with Jesse. Everybody was singing except for us. We were telling them to fuck off. We had a bit of banter going back and forth, with Isocracy and Op Ivy. Some people liked it and some people didn’t. We would have fake fights where we’d jump onstage and fight with ’em. It went over good with Jesse. Matt was good with it. Tim didn’t like it at all. Lenny didn’t like it at all. But in between songs we would be screamin’ and yellin’: “You guys fuckin’ suck! Fuck you!”

Jason Beebout:

“You’re breakin’ my heart! You should kick your own ass for suckin’ so bad!”

“You’re breakin’ my heart! You should kick your own ass for suckin’ so bad!”

Martin Brohm:

That was great fun. A lot of people would come to those shows who wouldn’t go to other Gilman shows. So you’d be out in the crowd going, “You guys are fuckin’ shit!” And these 14-year-old girls would be going, “Dude, what the fuck is your problem?”

That was great fun. A lot of people would come to those shows who wouldn’t go to other Gilman shows. So you’d be out in the crowd going, “You guys are fuckin’ shit!” And these 14-year-old girls would be going, “Dude, what the fuck is your problem?”

Tim Armstrong:

That was a part of the whole Isocracy humor. Heckling, garbage, I never took it personal. People probably did, though. All that shit was cool. That was just part of the territory.

That was a part of the whole Isocracy humor. Heckling, garbage, I never took it personal. People probably did, though. All that shit was cool. That was just part of the territory.

Matt Freeman:

They were fucking kooks. So when we got back from tour we did that Isocracy song “Rodeo,” as ska. That was funny, they were watching and—“Ah hah!”

They were fucking kooks. So when we got back from tour we did that Isocracy song “Rodeo,” as ska. That was funny, they were watching and—“Ah hah!”

Jeff Ott:

People would go out after shows and jump in people’s bushes all over the place, in the middle of the night. With the object being to destroy them. Literally. We’d get kids coming from the suburbs to see Op Ivy, to go out and jump in hedges.

People would go out after shows and jump in people’s bushes all over the place, in the middle of the night. With the object being to destroy them. Literally. We’d get kids coming from the suburbs to see Op Ivy, to go out and jump in hedges.

Jesse Michaels:

It was sort of an extension of skating.

It was sort of an extension of skating.

Jason Beebout:

It was a cop’s nightmare, just a bunch of fuckin’ 16-year-old douchebags running around the streets, with nothin’ to do at four in the morning. You’d go up into the Berkeley Hills where all the professors lived. They had these really expensive houses and nice cars. You’d find a really beautifully manicured hedge. Some were really good, some were really forgiving, others were soft and downy, and some were horrible.

It was a cop’s nightmare, just a bunch of fuckin’ 16-year-old douchebags running around the streets, with nothin’ to do at four in the morning. You’d go up into the Berkeley Hills where all the professors lived. They had these really expensive houses and nice cars. You’d find a really beautifully manicured hedge. Some were really good, some were really forgiving, others were soft and downy, and some were horrible.

Martin Brohm:

Your best bush was a finely manicured juniper. Because the juniper had good spring-back. You’d get in there and it’d pop you out. A lot of times, if they’re too soft, you’d jump in and go straight through it, and you’d land on whatever’s on the other side. Or you’d get stuck with one of the strong branches underneath. You’d get a juniper in the rib cage.

Your best bush was a finely manicured juniper. Because the juniper had good spring-back. You’d get in there and it’d pop you out. A lot of times, if they’re too soft, you’d jump in and go straight through it, and you’d land on whatever’s on the other side. Or you’d get stuck with one of the strong branches underneath. You’d get a juniper in the rib cage.

Jeff Ott:

Aaron Cometbus opened his head up.

Aaron Cometbus opened his head up.

Spike Slawson:

I landed on a stump that was cut at an angle.

I landed on a stump that was cut at an angle.

Lenny Filth:

I landed on a sprinkler head in front of the Ford place on San Pablo. I thought I broke my back.

I landed on a sprinkler head in front of the Ford place on San Pablo. I thought I broke my back.

Jesse Michaels:

The person who invented it, to me, was Noah from Christ on Parade. And he probably doesn’t get credit for it. But I remember hanging out with some people and he was doing it. We made a song about it. Maybe not the most well-advised song, but, yeah.

The person who invented it, to me, was Noah from Christ on Parade. And he probably doesn’t get credit for it. But I remember hanging out with some people and he was doing it. We made a song about it. Maybe not the most well-advised song, but, yeah.

What happened to your bush

It’s not the same

Something in your hedge

Made a violent change

We come we see

We dive and destroy

And annihilating shrubs is what we enjoy

Hedgecore hedgedive hedgecore

We’re doin’ hedges to stay alive

It’s anarchy night every night of the year

With chaotic mayhem

We keep your bush in fear

Terrorist assassins of creative gardening

Fucking up your hedge here’s what we sing

It’s not the same

Something in your hedge

Made a violent change

We come we see

We dive and destroy

And annihilating shrubs is what we enjoy

Hedgecore hedgedive hedgecore

We’re doin’ hedges to stay alive

It’s anarchy night every night of the year

With chaotic mayhem

We keep your bush in fear

Terrorist assassins of creative gardening

Fucking up your hedge here’s what we sing

—“Hedgecore,” Operation Ivy

Other books

Happy People Read and Drink Coffee by Agnes Martin-Lugand

The Bully Boys by Eric Walters

Ghost of a Chance by Green, Simon

Our Hearts Will Burn Us Down by Anne Valente

Divinity: Transcendence: Book Two (The Divinity Saga) by Reid, Susan

Mrs. Lizzy Is Dizzy! by Dan Gutman

Unconditionally (Brown County #4) by Amber Nation

Stunner by Trina M. Lee

Summer Storm by Joan Wolf