Girl at Sea

Authors: Maureen Johnson

Tags: #Italy, #Social Science, #Boats and boating, #Science & Technology, #Sports & Recreation, #Fiction, #Art & Architecture, #Boating, #Interpersonal Relations, #Parents, #Europe, #Transportation, #Social Issues, #Girls & Women, #Yachting, #Juvenile Fiction, #Fathers and daughters, #People & Places, #Archaeology, #Family, #Action & Adventure, #General, #Artists, #Boats; Ships & Underwater Craft

maureen johnson

For Mary Marguerite Johnson,

the world’s greatest mother,

arguably its best nurse,

and the person likely to find

the most safety violations in this story

Contents

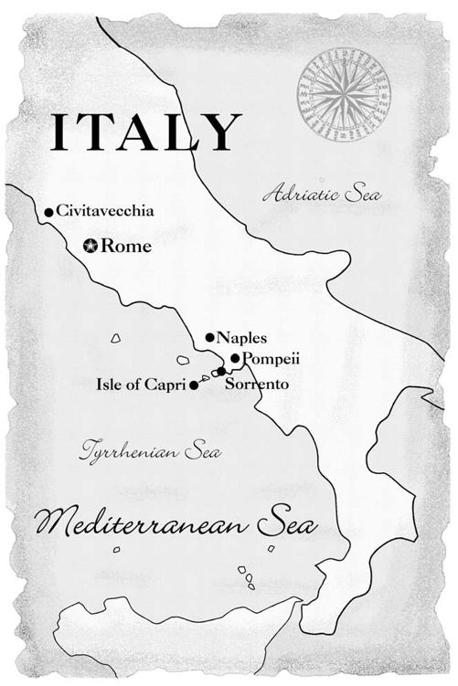

Map

vi

1

The Secret That Dare Not Speak Its Name

5

Where There Is a Balloon, There Is Always a Pin

14

22

29

41

Mental Scarring and Jokes That Aren’t Funny

50

59

70

77

93

98

116

126

133

142

A Brief History of Floridian Girl-Lifting

151

162

167

174

186

192

204

213

220

226

236

Do Not Push the Shiny Orange Button

244

248

260

269

276

293

305

313

316

Other Books by Maureen Johnson

Lightning flashed over Big Ben, and a bruise-like darkness draped over the dome of St. Paul’s. On the streets of London, sudden claps of thunder caused horses to start and carriages to collide. The British Museum was packed with people seeking shelter from the oppressive weather within its massive halls, among its great stones. Unfortunately, too many people had the same idea; there was hardly room for them. The pressure in the air grew as screaming children ran between the display cases and tables, knocking into them. Crowds bumped around the price-less Elgin marbles from the crown of the Parthenon.

Eighteen-year-old Marguerite Magwell slipped through easily, not really noticing the chaos that was going on around her.

She was even unaware of the ominous sky outside. If you had asked her at that moment if it was hot in the museum, she would not have been able to answer. Her own body was bone cold. The humidity that dampened her cornflower blue dress simply made 1

her colder. She was hatless and gloveless. Her blond hair was loosely pinned up and curled wildly in this intense weather. Her appearance was not a concern; she didn’t know what she looked like, didn’t care. The only thing that mattered was the small slip of paper she clutched in her right hand. In her mind there was one thought only:

go to Jonathan

. Jonathan Hill had been her father’s favorite student, besides herself. Jonathan needed to know. Jonathan could help her now, at the only time in her life when she truly did not know what to do.

Other people noticed her. Even in this state, Marguerite was striking, equal parts wild and delicate, with a face whose fine proportions could have been immortalized in marble. People eased aside as she pressed her way forward to the statue of Ramses II in the long Egyptian gallery. The statue occupied a place of pride in the columned hall. Marguerite fixed her eyes on the cold, pupil-less ones above her, the eyes of a king dead for thousands of years. She had never understood until this moment why the Egyptians tried so hard to preserve themselves after death. How wonderful it must have been for them to believe so strongly that the dead lived on, that they could be reached, that they would need their bodies!

No time to think about that.

She continued on, pushing between the overstuffed display cases and people, moving from room to room, feeling like she had less and less air to breathe. The door she was looking for was unmarked. Most people would not have been able to tell that it wasn’t just a wooden panel between two cases of monkey skulls.

The curators worked behind these secret doors, unseen by the populace, in offices even more crowded than the museum floor 2

itself. Having practically grown up in the museum, she knew exactly what she was looking for. Marguerite moved aside two little boys who leaned on the panel she required and pounded on the door with the flat of her hand. A moment later, a familiar face appeared, smiling, slightly dazed. Jonathan’s sandy hair was in need of a barber’s touch, and he had ink all over his long fingers.

“Marguerite!” he said, shifting his collar nervously. “What brings you to the museum today? Sorry, I’ve been writing all morning; I don’t want to cover you in this . . . Oh, I’ve just gotten it on my neck, haven’t I? Never mind. . . .”

Marguerite could not bring herself to say why she had come just yet. Her throat was dry, and it felt like a hand had grabbed it and was squeezing it.

“It’s very hot today,” he sputtered, noticing her distress.

“Would you care to take a walk around the courtyard with me?

They’re selling lemon ices in the square.”

“Lemon what?” she asked abruptly.

“Ices?” he repeated.

“Oh. Ices.”

There was a darkening at the windows, and a great crack of thunder broke above the museum, causing several ladies to cry out. A moment later, there was a pounding on the roof as the rain came down.

“Listen to that,” Jonathan said, looking up at the ceiling. “It’s like the great flood out there. I suppose that rules out the possibility of the lemon ices. Let me get the porter to start turning on the lights so that they—”

“I have news of my father,” she interrupted.

3

“Wonderful!” He touched her hand lightly. “How’s the work in Pompeii going? When does he arrive home? Did I get ink on you? Oh, I did, didn’t I? Here, let me—”

“He doesn’t,” she interrupted him again.

“What do you mean?” he asked, already grabbing for his hand-kerchief and dabbing the spot of ink on her hand unsuccessfully.

“His ship,” she managed.

“His ship?” he repeated. “What about his ship? Marguerite, are you well? Do you need to sit down? You’ve gone very pale.”

She held out her tightly closed fist, the paper sticking out of it. Jonathan carefully pried it loose. She watched him take in the words. He reached up and held the doorframe, then looked at her.