gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (37 page)

The reason behind this noticeable switch from wolf to fox, both of which were forms of the cosmic trickster and the star Alcor in Ursa Major, is easily explained. Whereas the wolf was important to the reindeer hunters of the East European Plain, the fox appears to have played a cosmological role among the Eastern Gravettian peoples of both Central Europe and the Russian Plain. The fox was also important among the Natufian communities of the Levant. Here the bones and teeth of the red fox have often been identified among the faunal remains found at occupation sites.

13

It was arguably for similar reasons that the fox and wolf were interchangeable in their role as cosmic trickster, since the animals meant different things to different cultures in different localities. In ancient Egyptian tradition, for example, the trickster god is Seth, whose animistic form is the

fenekh,

or desert fox, while for the Dogon of Mali in West Africa the trickster is Ogo, the pale fox.

The cosmic trickster, in all its forms, whether as the wolf or fox (or, indeed, the dog, dragon, lion, or any other type of animal) has the potential to quite literally bring about the death of the world through the collapse of the sky pole that holds up the heavens. The crucial knowledge of how to prevent this from happening was, quite possibly, the all-important remedy for the catastrophobia rife among the hunter-gatherers of southeast Anatolia in the wake of the Younger Dryas Boundary impact event.

This then was the knowledge very likely made available to the Epipaleolithic peoples of southeast Anatolia some twelve to thirteen thousand years ago. Those who offered this solution were, most probably, members of a Swiderian ruling elite—hunters, warriors, tool specialists, and shamans—whose journey probably begins as far west as Poland’s Vistula River and the obsidian sources of the Carpathian Mountains and ends with their entry into eastern Anatolia sometime during the Younger Dryas mini ice age, perhaps around 10,500 BC or slightly later. They are the face of the Hooded Ones, whose own great ancestors are most likely immortalized in the twelvefold rings of T-shaped pillars, not just within the large enclosures at Göbekli Tepe but also at the various other Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites throughout the

triangle d’or.

Yet we still need to better understand how exactly the incoming groups of Swiderians were able to convince the Epipaleolithic hunter-gatherers of southeast Anatolia to come together to create the first truly megalithic architecture in human history. How did this happen? It is a matter we address next.

26

STRANGE-LOOKING PEOPLE

C

an we imagine the sense of fear and uncertainty that must have existed in the minds of the Epipaleolithic peoples who lived in the vicinity of Göbekli Tepe during the Younger Dryas mini ice age, ca. 10,900–9600 BC? The golden age once spoken about by the elders was now little more than a utopic dream. Since the great fire from the sky and the time of perpetual darkness and constant rain, when the land had sunk beneath the waters, the world had been an entirely different place—cold, bleak, dry, and almost devoid of the herd animals that had provided life and sustenance to so many.

It almost seemed as if the animal spirits that had addressed their every need had now deserted them, perhaps through their misdeeds in the years leading up to this terrible change in the world. What is more, there was no assurance that these great catastrophes would not happen again and again, until finally nothing more was left, only the darkness that prevailed before time began.

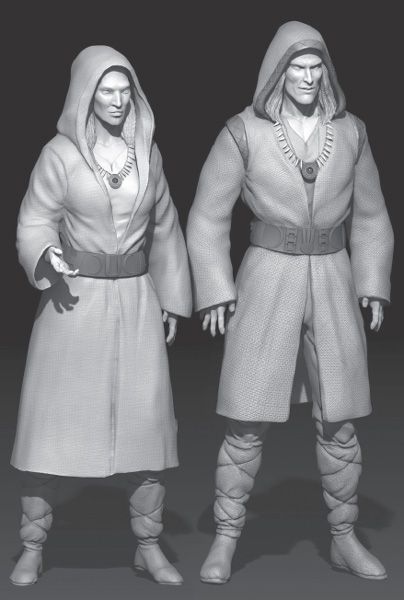

Then one day a group of tall, strange-looking people of striking appearance, with elongated heads, long faces, high cheekbones, strong jaws, and prominent brow bridges due to their ancestry as Neanderthal-human hybrids, enter the settlement. Perhaps they wear long, hooded garments made of linen, flax, or hide, as well as belts decorated with strange symbols, leather leggings, and boots made out of animal skin (a reconstruction by graphic artist Russell M. Hossain is offered in figure 26.1). They are clearly hunters, with bows and arrows slung over their backs and items of personal adornment gained from the chase. They have necklaces of wolf or fox teeth; strings of beads made from ivory, bone, shell, antler, and stone; as well as insignia of office that hang like medallions around their necks. Alongside them are others, peoples of the region, identified as post-Zarzian shamans, warriors, and tradesmen.

Figure 26.1. 3-D digital sculpts by artist Russell M. Hossain depicting the Hooded Ones—the Swiderian power elite behind the creation of Göbekli Tepe. Their physical traits are derived from anatomical evidence of the Brünn population and the Sungir burials of Russia, coupled with a knowledge of Swiderian physiognomy, which suggests Neanderthal-human hybridization.

Leaders of the group will have addressed representatives of the community, showing them examples of exotic materials such as obsidian from Bingöl and Lake Van and flint from farther afield. They might have offered to supply these and other valuable commodities, and then, after gaining the community’s trust, the hooded strangers will have revealed the true purpose of their mission. Their sky magic had successfully combated the baleful influences of the canine trickster, who had attempted to destroy the world at the time of the great fire from the sky. This knowledge they would now pass on at a price. However, to successfully bind the cosmic trickster and ensure the future stability of the sky pole that supported the heavens, the community would have to give up their hunting lifestyles and learn to work together to put into practice this powerful magic.

COMMUNITY NETWORKING

The chances are that this incoming group, of Swiderian descent, visited other Epipaleolithic communities as well, offering exotic materials to their inhabitants while at the same time spreading their potent message and showing their control and influence over the cosmic trickster, perhaps by predicting the appearance of short-period comets. Eventually the Hooded Ones gained control of each and every one of the settlements they entered. When simple exchanges did not work, open conflict might have ensued, although very likely the strangers set existing allies against confrontational groups or tribes to quell any unrest.

This then was very likely the beginning of a type of regional supremacy instigated by the incoming power elite to bring about the building projects that would eventually lead to the creation of major cult centers such as Göbekli Tepe. These stone sanctuaries would function as axes mundi, terrestrial turning points of the heavens, their central pillars acting as gateways or portals to a perceived sky world existing in the direction of the constellation of Cygnus. From these enclosures rites of birth, death, and rebirth would be enacted and the baleful influence of comets countered by shamans.

THE WALLS OF JERICHO

How exactly the ruling elite might have convinced the indigenous peoples to create monumental architecture on such a grand scale remains a mystery. Fear is the most obvious answer—fear that it would all happen again if they did

not

create these monuments in exactly the fashion prescribed. Yet as Klaus Schmidt is at pains to point out, nothing like Göbekli Tepe existed anywhere else in the world at this time. That said, monumental architecture

was

being built contemporary to the construction of Göbekli Tepe 420 miles (675 kilometers) away at Jericho, in what is today the Palestinian territories.

A Natufian site existed at Jericho during the Younger Dryas period, but it was not until the arrival of a Pre-Pottery Neolithic A culture that the place was transformed into a major town complex. Very quickly the inhabitants felt the need to surround the 10-acre (4 hectare) settlement with a stone wall 10 feet (3 meters) thick and 13 feet (4 meters) high, which extended around the entire occupational mound for a distance of nearly half a mile (800 meters).

In addition to the great wall, the Jericho inhabitants constructed an enormous stone tower 33 feet (10 meters) in diameter and 28 feet (8.5 meters) high, accessed through a west-facing doorway that connected with a stone staircase of twenty-two steps.

As well as the almighty stone tower and perimeter wall, a gigantic ditch was cut out of the limestone bedrock around the outside of the settlement. This was 9 feet deep (2.75 meters), 27 feet wide (8 meters), and more than half a mile (over 800 meters) long, with one prehistorian describing it, aptly, as “a considerable feat in the absence of metal tools.”

1

Clearly, something major was occurring at Jericho. The inhabitants seemed eager to keep something out, and it was not simply wild animals or the elements. An aggressor lurked out there somewhere, who was perceived as a potential threat to the well-being and lifestyle of the Jericho population, which numbered in the hundreds.

The existence of sites such as Jericho tells us that the capability to supersize monuments and structures

was

present among the Pre-Pottery Neolithic peoples of the Fertile Crescent at this time. Yet clearly, before the construction of Göbekli Tepe and Jericho, the motivation to create large-scale stone buildings for specific magico-religious purposes was simply not present. Something then changed, and all the indications are that the hunter-gatherers of southeast Anatolia and the Levantine corridor were responding to events happening in their world, and in the opinion of the author that was the Younger Dryas Boundary impact event and the incredible state of fear it left in the world’s human population in its aftermath. However, even then it had taken the intrusion of a powerful elite of European descent to inspire the creation of monumental architecture with the intent of curbing wide-scale catastrophobia once and for all.

SCHMIDT AND THE SWIDERIANS

As controversial as these theories might seem, even Klaus Schmidt has had his eye on the Swiderians as being in some way instrumental in what was going on in southeast Anatolia at the commencement of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic age. Not only does he acknowledge the similarity between the Natufian gazelle hunters and the “reindeer hunters of the North,”

2

that is, those in Europe, and admit that “perhaps there was some kind of connection or communication between the societies of Turkey and those around the Black Sea and the Crimea,”

3

but in a paper written for the journal

Neo-lithics

in 2002, he even names the Swiderians

4

when he writes:

The late Paleolithic Swiderian reindeer hunters of eastern Europe had a similar hunting strategy [to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic peoples of the Upper Euphrates] using the seasonal wandering of reindeer and their crossing of big rivers such as the Vistula (Weichsel).

5

Schmidt obviously recognizes something of the European hunting tradition in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic world that existed in the lead-up to the construction of Göbekli Tepe and other religious centers in southeast Anatolia during the tenth millennium BC. He singles out the Swiderians as an example of these hunting strategies, when he could have mentioned the Hamburgian-Ahrenburgian cultures of North Germany, the Brommian-Lyngby cultures of Denmark and Scandinavia, or indeed any one of a number of other Paleolithic hunting traditions that thrived in Europe toward the end of the Upper Paleolithic age. Why? Was it that he had just read an article on the Swiderian culture and wanted simply to use them as an example of this hunting strategy, or does he too have a sense of their presence at Göbekli Tepe?

The greatest clue is in the German archaeologist’s suggestion that “perhaps there was some kind of connection or communication between the societies of Turkey and those around the Black Sea and the Crimea.”

6

When he said these words to osteoarchaeologist and TV presenter Dr. Alice Roberts, he almost certainly had in mind the incursions of the Polish Swiderian tradition into the Crimean Highlands, immediately above the Black Sea. A simple boat journey along its eastern coast, or a gradual migration overland through the Caucasus Mountains and the Armenian Highlands, would have brought these European hunters directly into contact with the Epipaleolithic peoples of southeast Anatolia, and Schmidt knows this very well. However, I suspect that until now he has found nothing concrete at Göbekli Tepe that might help confirm these surmises, despite the fact that worked flints have been found that are more-orless

identical

to Swiderian tanged points.

THE END OF GÖBEKLI TEPE

The world of Göbekli Tepe remains truly bizarre, and so far we have only been able to scratch the surface of what was really going on here nearly twelve thousand years ago. Having started with grand structures featuring monoliths 18 feet (5.5 meters) high, the Göbekli builders ended up settling for bathroom-size rooms, with standing stones no more than a few feet in height and communal benches like something you might find in a family-size Jacuzzi.