Golden Hill (33 page)

Authors: Francis Spufford

‘You should try the experiment of seeing yourself through my eyes.’

‘What would I see?’

‘Beauty. – And rage, and bitterness, and solitariness, and a very foul temper; but first of all, beauty. You make everything else in a room look dull. Your face is more alive than anyone else’s, to me. All the other faces are dirty windows, to me, smeared with chalk and street-spatter; yours is clear through, to the soul behind. – And I know the shape of your mouth by heart. I know the colour of your eyelids when they are closed. I know your long legs and your careless walk. And what I do not know, I would like to learn; all of it, for many years, gently, greedily—’

Too much. She had been coming closer to him, stepping wonderingly in, as if he had some small flame in his hands she might warm herself at: but now she blushed, the rose-brown going to glaring unhappy carmine, and she drew suddenly back.

‘That’s enough,’ she said nervously. ‘Stop; that’s enough of that. What are you asking me, Smith? What are you proposing? Be plain.’

‘I am asking you to come out of the cage. The door is open.’

‘No; no! I don’t want to hear it in pretty figures. I am a merchant’s daughter. We sell cloth and rum and metal goods. We ship grain. We lend at interest. We buy mortgages. We are not poets. You want me to – run away with you? And be – what, exactly? Your wife? Your mistress? An entertainment for the road?’

Smith hesitated again. He was impeded by the reflection that, if she came with him, and five minutes later as promised he explained himself to her, she might by no means then agree to stay with him. He was sure of his own intentions, but he was not so sure of her that he could rule out her being horrified. It was difficult to make somebody a declaration of honourable devotion, when you were conscious of this conditional check to it, so

near a prospect; this no that might follow so hard on the heels of a yes. And what would he do then? Would he leave her at the last house in New-York, at the gate of Rutgers’ Farm or at the snowy crossroads in Greenwich, after an engagement of five minutes’ duration? This stumbling-block, this awkward juncture at which he was trying to elicit trust without yet bestowing it whole-heartedly himself, he had contrived to glide over, in his planning, without examining its difficulty too closely. Yet here it was, arrived at. – Perhaps he must take things by stages.

‘As … my friend, to begin with?’

‘Oh, your

friend

,’ she said, with a relieved derision. ‘What an anti-climax. What a very small delivery after such a mighty labour.’

‘I meant to suggest, that you would be protected; honoured, as a friend; that nothing would be expected of you, at

all

, until you knew the whole truth; till you were able to consider without, um, prejudice, the proposal I would

like

to make you. To be making you

now

. Tabitha, I

want

to say, just, m—’

‘Heavens, how your eloquence has flown out the window all of a sudden,’ said Tabitha, ignoring the later parts of this speech. ‘You know, your reputation for protecting your friends is not very good, lately. It is a dangerous business, being a friend of yours. Do you think I would end up dead in a ditch, too?’

‘I promise—’

‘Where are you going, anyway?’

‘I … can’t tell you.’

‘I

see

. How tempting! I might end up dead in a ditch on the way to Trenton; or dead in a ditch on the way to Philadelphia; or, maybe—’

‘Tabitha—’

‘—or

maybe

, dead in a ditch on the way to Boston! Wouldn’t that be exciting? I have always wanted to go to Boston!’

‘

Tabitha

.’

He held her with his eyes, and she steadied somewhat, though she was breathing fast. They seemed to be going backward; he seemed required to make his most delicate declarations as she skittered away from him into hostile gaiety.

‘What?’

‘You will be surprised, if you come with me, yes: and perhaps you will be shocked, and the – complexion of things – might seem very different to you, from what you had expected; but I swear, I swear to you with utmost seriousness, that you would not learn anything about me that made any essential difference to what you know of me now. I am as you see me. You may trust what you know. Please, trust what you know.’

‘I don’t see an occasion for trust,’ she said. ‘I see a resistible invitation to ruin myself. I see you asking me to make a mad gamble with my future. You are a felon, and a liar, and a mountebank, and careless with those who love you. And you have been unfaithful to me with that

slug

of a woman before we even begin.’

‘Those are all true,’ said Smith. ‘But they’re not the reason you hesitate, are they? Not really. The real reason is that you’re afraid to let go of what you know, even if you don’t like it; even if you hate it; even if it won’t let you breathe. Come on, Tabitha. I dare you. The world is wide. The cage door is open. Come out. Won’t you come out?’

‘I don’t know,’ she said in a tiny voice. She had wrapped her long arms around herself, and was looking at the floor.

‘What is there for you here?’ he said, coming closer. ‘Nothing. Nothing but the chance to make trouble; and that isn’t enough

for a life, you can’t make a life out of that, can you? Come away. Bring your temper and your tongue, and come with me, love.’

‘I don’t

know

,’ she said, louder, with a dry intensity, with an anguished deliberateness, as if she could not let go of not letting go.

He took the last step and put his hands on her shoulders. He felt them shifting, warm and live, the whole slender quire of bone and muscle and spirit that composed her, moving articulate beneath his fingers, trembling. She looked up at him with big astonished eyes, and it seemed to him that her trembling was between possibilities, that she stood irresolute on the brink between two different lives; not strong enough, he thought, to decide to jump, yet too strong to let herself be carried over passively. He tried to look courage into her. She took a gulping breath, he thought to steady herself, but the tremble grew bigger, grew to a positive shake, so that she rattled from side to side in his hands; and when she took another, still more convulsive, her eyes still fixed on his, her face began to heave and twitch, and to pull out of true. Something was coming loose in her, boiling up from beneath, struggling to the surface. – He nodded. – Her eyes swam, and he expected tears, but the drowning look in them wavered, held; helpless, unable to help herself, but strangely, very strangely,

content

, almost smiling, as if she had decided not to help herself, but to surrender to some oncoming pleasure. And her mouth kinked, stretched, worked, widened, into a desperate grin; and then stretched on and out and into a vibrating black square from which burst a scream so loud and painful at close quarters it felt as if a knife had been stuck in Smith’s ear.

He reeled back with his hands clapped to his head, and without ceasing to scream she whirled about and began to sweep objects

off the mantel, seizing them in spasms and twitches and flinging them down to shatter on the boards. A china shepherdess – smash – the matching shepherd boy – smash – the clock and the Meissen candle-sticks – smash, smash, smash.

Smith tried to reach into the whirlwind, and she snapped at him with her teeth. Feet came pounding up the stair; Zephyra burst into the room, still holding the cloth with which she had been polishing silver.

‘What you said to her? She not like this for months!’

‘I—’ said Smith, ‘I – just—’

‘Step back from her. Mistress,’ said Zephyra, who rather than entering the zone of Tabitha’s fury was carefully drawing pieces of furniture away from her, ‘you settle down, now; it be all alright; you be a good girl, and take some breath; you hush yourself, now.

You

,’ she said to Smith, with a furious jerk of the chin, ‘go!’

‘But—’

‘Don’t you see you make it worse?’

‘But – I am responsible—’

‘Go!’

Seeing that Smith still gaped, and that Tabitha seemed now to be locking into place, a stationary banshee with fists rigid at her side, eyes closed, lost in an ecstasy of protest, Zephyra, sighing, grabbed his sleeve and towed him from the room, and down the stairs.

‘You go before the Mister comes,’ she hissed.

It was too late for that, however. Lovell, issuing falteringly out of the passage-way from the counting-house, moving as if against a hurricanoe-headwind of his own reluctance, met them at the foot of the stair with his hands clutching at his wig.

‘

You!

’ he cried. ‘What has – what have you—?’ He made a grab

at Smith’s lapel, but the shrieks from above, the rising howls, distracted him, and instead he pushed past. ‘Oh God, not again,’ he could be heard to mumble.

‘Now, out!’ said Zephyra, and she thrust Smith ahead of her along the passage; to the street-door, and out into the cold.

And stopped dead, on the threshold, seeing what was waiting for Smith there in the snow: what he had accomplished at last, in New-York, with his thousand pounds.

Mr Smith had been shopping in the slave-market. There, in two of the largest possible sizes of sledge, hitched up to driving horses, twenty or so silent Africans were packed. He had dressed them all in winter furs, but he must have selected his purchases according to some peculiar principle, for they were an unlikely crowd to choose for labour: old women, children, sullen-looking wenches, a girl with a wall-eye, another whose visage had the far-off serenity of deafness, and a crew of men most owners would have found intolerably villainous, for they were blue-black of skin, with the nakedly belligerent expressions of those not yet resigned to the country. Two had tribal scars.

Smith bolted across the snow-crust of the street in two bounds, like a cat escaped from a scalding. But then surprised her by turning back, when he had reached his strange cavalcade. He was weeping, but he smiled, and held out his hand to Zephyra.

‘

Aane, me ara ni nnipa a wo twen no

,’ he said.

What a difference a frame makes. The aching winter light that glared up into the glassy humour of her eye from the street, where the blue shadows were beginning to lengthen, was just the same; the sight before her was unaltered; but in her unmoving dark face, armoured to stillness by long sorrow, the pupil through which the light flowed in flared wide of its own accord, in miniscule

astonishment, for the meaning of the scene was suddenly reversed. There was Smith, still shaking with the early shock of what he had just lost, and with much more to feel of it ahead of him, and yet with a tension falling from his face – no, more than that, with a whole role falling from it, in flakes and pieces and cascading blocks, like a collapsing wall – that had been maintained in place without a pause since he landed. And there was Achilles from the Fort, who, the word had been, was sold now down to a tobacco farm in the Carolinas, here instead in gloves and furs, holding the reins of the front sleigh to drive it; and there was Smith, jumping up beside him, and the others around him all budging up, shuffling up, to give him his place among them. Smith looked at her again; again held out his hand. The messenger of her new fortune had indeed arrived; if she was willing to hear him.

Which she was. Zephyra dropped the rag she was still holding, and without looking back, without even closing the door, clasped her hand across her belly and walked out of the house on Golden Hill for ever: a step, and another step, and one more step through the crunching snow, to the dark hands reaching to lift her up. Ten seconds later, the street was empty.

Banyard & Hythe, Partners: Mincing Lane, London, 10th December 1746

My dear Sir,

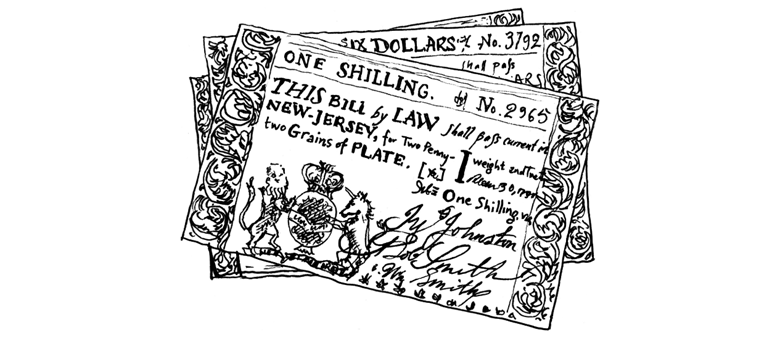

I received yours of the 2nd November, and confess Myself surprised at its indignant Tone. For though it is true, that the Balances owing between your Office and ours, are usually settled by means of the Jamaica Trade, yet, a Debt is a Debt, and while it rests upon our Books, it is our Right to issue any Bills whatever upon it that We see fit. The mulatto Smith having presented Himself here with a thousand Pound (Sterling) in right Currency, it was a Matter of straightforward Advantage to Us, to sell Him immediately what He desired to buy immediately.

The Bill is a true Bill and may therefore be paid with Confidence. Nevertheless, it is understandable that You may have been taken aback by his sudden Appearance with it, and for your greater Surety of Mind, We have made the Enquiries concerning Him that You have requested.

The Tale is certainly a striking One. Richard Smith is, it seems, the Descendant of a Slave of the late Lord ––— (the present Lord ––—’s Father) by Way of two Generations of Marriage to Englishwomen. His Grandfather Hannibal was a

favourite Page of this elder Lord’s Wife, who being brought to England in the Seventies of the last Century, was enfranchised at his Majority and became a Servant, taking the Sur-Name of Smith. Or, truer to say, became as it were a favoured Ward of the Family, to the Extent that his Son (your Smith’s Father) was upon showing Proof of promising Parts, actually sent to Oxford as a Servitor or Scholar-Servant to Lord ––—’s Son, and later rewarded by the Living of one of the Churches in Lord ––—’s Gift, and consequently settled there in Dorset as a country Parson, where He presently remains. The same Strategy of Benevolence was purposed to be followed for the Parson’s Son, but the Boy ran off, pertly objecting to the Fate planned for Him. Rather, He endeavoured to make his own Way, here in the City of London, tricking Himself out first as a Dancing-Master, where He had but little Success, and then as an Actor in small Parts: where He shone more, being as You will have observed handsome of Face and pleasing of Manner, yet not so much as to secure Himself a Competency. This He found instead as Secretary or Factotum to the Mimick Club of Drury Lane, a dining Society not unlike the Beefsteak, where He has mingled for the last two Years with a Scattering of Persons prominent in Drama, the News-Sheets, and the Exchange.

But the Errand on which He came to You proceeds, it seems, from his Sunday Affiliation rather than his Week-day one. He is a Worshipper, in a small Congregation where the Fringes of Aristocratic Zeal meet London’s Population of emancipated Africans: the Countess of Malmesbury’s Abyssinian Connection. This Group receiving a Bequest of a thousand Pounds from one of its Patrons, it was decided that it should be laid out for the Purchase, the Freeing, and the Establishing in Independency

of their Country-Men and -Women. New-York was chosen as a Market far enough from the West Indies Hub of the Trade for the Transaction to be unobtrusive, and Richard Smith volunteered to accomplish It, as the Person among Them most fitted to pass without Difficulty in different Companies. He had a written Commission for the Business in his Pocket-Book, which He shewed Me.

The Bill, then, to repeat the essential Point, is good, and You may pay It without Demur. Indeed, if the Seas be as usual, You will have paid It long before this Assurance can reach You. But I trust this Information will set your Mind at Rest, and that, after the initial Surprise, the Transaction proceeded on your Side without any further Difficulty or Perturbation.

With a warm Protestation of the Value we place upon our long Association with the House of Lovell, and my best Regards to Mr Van Loon, I have the Honour to remain,

Your Servant,

Barnaby Banyard