Goodbye, Darkness (55 page)

Off Motobu, Japanese scuba divers disappear under water and reappear triumphantly holding aloft exotic shells. The Americans have built two golf courses, countless tennis courts, and athletic fields. The Japanese enjoy them very much. Sometimes they play against Americans. When they win, they crow. The Americans are good losers, and they are acquiring a great deal of experience in that. Out in the boondocks you can still find rice paddies, but with rice selling at ten dollars for a twenty-five-pound blue plastic bag, the magnificent hillside terraces which once supported thousands of paddies have disappeared; sugarcane and pineapple plantations, which need far less irrigation, are far more profitable. And though many of the old lyre-shaped tombs still stand, the new mausoleums lack the lyre design. Instead they are small, and, being built of cinder blocks, cheap. One entrepreneur is erecting three hundred of them on Motobu. Reportedly he is giving serious consideration to a suggestion, made in jest, that he call it Forest Lawn East.

There are about thirty-five thousand Americans on the island, ten thousand of them in the Third Marine Division. Okinawa is considered good duty. Since Vietnam-bound B-52s are no longer serviced there, it is also light duty, and now that the old DUKWs have been replaced by the more efficient LBTP-7s as amphibious workhorses, landing maneuvers are far easier. The U.S. PX complex at Camp Butler, a small city in itself, is more impressive than any shopping center I've seen in the United States. Local entertainment is provided by bullfighting, sumo wrestling, and habu-mongoose fights. Bullfights aren't bloody. The matador carries a heavy rope. His job is to loop it around the bull's horns and pull, persuade, or trick the animal out of the ring. Sumo wrestling, subsidized by local businessmen, is very popular with GIs and Marines. It is more psychological than physical. Two grotesque, 350-pound Japanese men circle one another again and again, making little movements and twitches which, one is told, have enormous symbolic significance. The actual struggle, the period of contact, lasts no more than thirty seconds, and the wrestler, like the bull, loses when he is forced to leave the arena. The popularity of the fights between mongooses and habus — the habu is a poisonous snake, much feared — is peculiar, because the mongoose always wins. But the Americans love to watch them, too.

The more they like it, the more they try to integrate themselves into the local culture, the more the islanders exclude them. Before the war, Okinawa's inhabitants, like Korea's, were little more than colonial subjects of the emperor. Since the spring of 1972 the island has been the forty-seventh prefecture (

ken

) of Japan, with a bicameral legislature which swarms with political activity. Although the U.S. victory in 1945 paved the way for this, Okinawan politicians and intellectuals resent the American presence among them. When they say “Us,” they mean themselves and the Japanese; when they say “Them,” they are talking about Americans. From time to time they stage demonstrations to remind the world of their hostility toward Them, though they know, as everyone who has mastered simple arithmetic knows, that an American departure would be an economic disaster for the island, ending, among other things, the $150 million Tokyo pays Okinawan property owners as rent for land occupied by U.S. forces. This paradox, of course, is not unique in history. The British learned to live with it, realizing that the world's most powerful nation is the obvious choice for anyone in need of a whipping boy. When I recall the sacrifices which gave the Okinawans their freedom, the slanders seem hard. Then I remember the corpse of the girl on the beach; our patronizing manner toward a little Okinawan boy we picked up as a mascot and treated like a household pet; the homes our 105-millimeter and 155-millimeter guns leveled; the callousness with which we destroyed a people who had never harmed us. The Americans of today may not deserve the slurs of the demonstrators, but the fact remains that more than seventy-seven thousand civilians died here during the battle, and no one comes out of a fight like that with clean hands.

That night in the Okinawa Hilton I dream of the Sergeant, the old man, and their hill. It is a shocking nightmare, the worst yet. I had expected irony, scorn, contempt, and sneers from him. Instead, he is almost catatonic. He doesn't even seem to see the old man. His face is emaciated, deathly white, smeared with blood, and pitted with tiny wounds, as though he had blundered into a bramble bush. His eyes are quite mad. He appears so defiled and so miserable that on awakening I instantly think of Dorian Gray. I have, I think, done this to myself. I have been betrayed, or been a betrayer, and this fragile youth is paying the price.

Mea culpa, mea maxima culpa

. And for this there can be no absolution.

But I cannot leave it at that. Despite my disillusionment with the Marine Corps, I cannot easily unlearn lessons taught then, and as the youngest DI on Parris Island can tell you, there is no such word as impossible in the Marine Corps. There must be more on this island than I have seen. And there is. Next morning I explore the lands beyond the neon and all it implies, and find that the island's surface tawdriness is no more characteristic of postwar Okinawa than Times Square is typical of Manhattan. Hill 53, for example, once an outer link in the coast-to-coast chain of the Machinato Line, is now shared by an amusement park and a botanical garden. The peak provides a superb view of modern Naha. Looking in that direction through field glasses, it is satisfying to see that the city's tidal flats, where we trapped a huge pocket of Nipponese after Sugar Loaf had been taken, have been filled in and are part of the downtown shopping center. The city's suburbs reflect quiet good taste: flat-topped stucco houses roofed with tiles and shielded for privacy by lush shrubs.

The pleasantest surprise is Shuri, the Machinato Line strong-point which was second only to Sugar Loaf in Ushijima's defenses. Japanese tourists seem to prefer visits to the Cave of the Virgins, or a descent of the 168 sandstone steps that lead to the Japanese commanders' last, underground command post on the island's southern tip, but to me Shuri is more attractive and far more significant. Commodore Matthew C. Perry first raised the American flag over Shuri Castle on May 26, 1853; the Fifth Marines did it again on May 29, 1945. Since 1950 the ruins of the castle's twelve-foot-thick walls — some of which have survived, curving upward with effortless grace — have enclosed the University of the Ryukyus, Okinawa being the largest island in the Ryukyu Archipelago, and dotting the ridges flanking the university are modest, immaculate, middle-class homes. The castle-cum-university is on Akamaruso Dori, or Street, on the opposite side of which are swings, jungle gyms, and sandboxes. Under the shade of a tree in one corner stands an old Japanese tank, rusting in peace. None of the children in the little park pay any attention to it, and neither, after all I've seen, do I.

Before leaving the island I want to pay my respects to scenes once vivid to me. This seems a recipe for frustration, because most of them are gone. Green Beach Two, where my boondockers first touched Okinawan soil, is remarkable only for a silvery petroleum storage tank and two fuel pumps. My leaking cave near Machinato Field is gone; so is the field; only a renamed village, Makiminato, remains, and there is nothing familiar in it. The seawall on Oroku Peninsula and the tomb where I nearly died have completely vanished; a power station has replaced them. Motobu Peninsula, still clothed in its dense jungle, is the least-changed part of the island. The trouble here is not the absence of memorabilia. It is, once more, in my aging flesh. Precipices I once scaled effortlessly are grueling. Nevertheless I make it up the peninsula's peaks, Katsu and Yaetake. The pinnacles there provide first-rate views of the peninsula, and my presence on them attracts inquiring guards. I have been trespassing, once more, and I have been caught. But the guards are more curious than punitive, and presently I am talking to a voluble Japanese technician, Mr. Y. Fujumura. He explains that the peaks are used for Japanese and U.S. Signal Corps equipment which relays long-distance telephone calls, monitors radio traffic, and eavesdrops on phone conversations as far away as North Korea. He provides details. I understand none of them. We part, and on my way once more, checking my notes, I conclude that I have touched all bases on Okinawa.

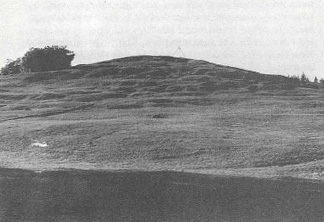

I am wrong. I left the United States believing that a revisit to Sugar Loaf was out of the question because it had been bulldozed away for an officers' housing development. In La Jolla, General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., the retired Marine Corps commandant, said he had been in the neighborhood recently; he assured me that the hill just wasn't there any more. But I ask Jon Abel and Top Milton to join me in a visit to the development anyway. There we pass a teen center, turn from McKinley Street to Washington Street, and, as I give a shout, come to a complete stop.

There it is, a half-block ahead. I am looking at the whole of it for the first time. It is the hill in my dreams.

Sugar Loaf Hill.

Jon and Top, almost as excited as I am, begin digging out old maps, which confirm me, but I don't need confirmation. Instinctively I look around for patterns of terrain, cover and concealment, fields of fire. To a stranger, noticing all the wrinkles and bumps pitting its slopes, Sugar Loaf would merely look like a height upon which something extraordinary happened long ago. That is the impression of housewives along the street when we ring their doorbells and ask them. They are wide-eyed when we tell them that they are absolutely right, that those lumps and ripples once were shell holes and foxholes. Now a mantle of thick greensward covers all. I remember Carl Sandburg: “I am the grass … let me work.”

Up I go — no gasping this time — and find two joined pieces of wood at the top, a surveyor's marker referring to a bench mark below. I take a deep breath, suddenly realizing that the last time I was here anyone standing where I now stand would have had a life expectancy of about seven seconds. Today the ascent of Sugar Loaf takes a few minutes. In 1945 it took ten days and cost 7,547 Marine casualties. Ignoring the surveyor's marker, I take my own bearings, from memory. Northeast: Shuri and its university. Southeast: Half Moon; officers' dwellings there, too. South-southwest: one leg of Horseshoe visible, and that barren. Southwest: Naha's Grand Castle Hotel, once a flat saucer of black ruins. And beneath my feet, where mud had been deeply veined with human blood, the healing mantle of turf. “I am the grass.”

I the Lord am thy Saviour and thy Redeemer.

“Let me work.”

Sacred heart of the crucified Jesus, take away this murdering hate and give us thine own eternal love.

And then, in one of those great thundering jolts in which a man's real motives are revealed to him in an electrifying vision, I understand, at last, why I jumped hospital that Sunday thirty-five years ago and, in violation of orders, returned to the front and almost certain death.

It was an act of love. Those men on the line were my family, my home. They were closer to me than I can say, closer than any friends had been or ever would be. They had never let me down, and I couldn't do it to them. I had to be with them, rather than let them die and me live with the knowledge that I might have saved them. Men, I now knew, do not fight for flag or country, for the Marine Corps or glory or any other abstraction. They fight for one another. Any man in combat who lacks comrades who will die for him, or for whom he is willing to die, is not a man at all. He is truly damned.

And as I stand on that crest I remember a passage from Scott Fitzgerald. World War I, he wrote, “was the last love battle”; men, he said, could never “do that again in this generation.” But Fitzgerald died just a year before Pearl Harbor. Had he lived, he would have seen his countrymen united in a greater love than he had ever known. Actually love was only part of it. Among other things, we had to be tough, too. To fight World War II you had to have been tempered and strengthened in the 1930s Depression by a struggle for survival — in 1940 two out of every five draftees had been rejected, most of them victims of malnutrition. And you had to know that your whole generation, unlike the Vietnam generation, was in this together, that no strings were being pulled for anybody; the four Roosevelt brothers were in uniform, and the sons of both Harry Hopkins, FDR's closest adviser, and Leverett Salton-stall, one of the most powerful Republicans in the Senate, served in the Marine Corps as enlisted men and were killed in action. But devotion overarched all this. It was a bond woven of many strands. You had to remember your father's stories about the Argonne, and saying your prayers, and Memorial Day, and Scouting, and what Barbara Frietchie said to Stonewall Jackson. And you had to have heard Lionel Barrymore as Scrooge and to have seen Gary Cooper as Sergeant York. And seen how your mother bought day-old bread and cut sheets lengthwise and resewed them to equalize wear while your father sold the family car, both forfeiting what would be considered essentials today so that you could enter college.