Grave Concern (29 page)

Authors: Judith Millar

Tags: #FIC027040 FIC016000 FIC000000 FICTION/Gothic/Humorous/General

“Wear rubber boots,” Mary said, and hung up.

“Like hell,” Kate replied to the tone.

Kate and Mary climbed out of Mary's truck and strolled down a shady, pine needle-strewn path to the museum, set back in a grove of trees. All around them, Canada's birthday was in full swing.

In a clearing to their left, a very small, old-fashioned carousel trucked from some distant location was obviously proving a head-scratcher for those in charge of starting it up. Farther along, beside the museum, people were setting up trestles and hauling in logs for the traditional log-sawing competition to take place in the afternoon.

Farther on, a crazily painted truck proclaimed

EXTRAORDINARY WAYNE AND HIS EXOTICS

. On the far side of the truck, through the space between cab and cargo hold, Kate spied a man demonstrating something to a spellbound group of kids. While she couldn't see the man's face â his back was to her â she

could

see the boa he wore, and not a feather one either. This boa was a living scarf, writhing about his neck â¦

A blurred face hovered over Kate. A small voice spoke in her head, as though from a great distance.

Fainted

,

she's just fainted

, it said. A voice Kate knew, but couldn't place.

The voice grew clearer, loud. “Kate â Kate dear, wake up!” Mary gently rubbed Kate's cheek and felt her pulse. “Yes, thanks. Just over here is fine.”

“Mary?”

“I'm here. This nice man is just carrying you to a quiet spot. Yes, she'll be fine, thanks. Thank you so much.”

“Who's that? What happened?” muttered Kate.

“You fainted, dear. One of the First Nations dancers has just carried you over here by the tree. You basically walked into him, just before you collapsed.”

“I fainted?” said Kate.

“Indeed.”

“I'm not a fainter, Mary.”

“You are now,” Mary said. “Just between you and me, dear, I'm feeling a tad faint myself.” Mary lowered her voice to a loud whisper. “His biceps were

to die for

.”

“I w-walked into someone?”

“Yes, dear, the most gorgeous man. Half-naked, dear, with feathers up the ying yang. You really should watch where you're going. I certainly did. What on earth were

you

looking at?”

“Extrrodinâ ”

“Eh? Let me assure you, whatever caught your fancy was not nearly as extraordinary as what you missed. By the way, he wanted to apologize but I thought it best he wasn't there when you woke up. He was all painted up, I thought he might give you a scare.”

“All â all painted up? Extr-orrd-inary Wayne?”

“Extraordinary who? No, dear, the hunky Indian. Look, he's over there with the others, watching the barbershop quartet.”

Kate lifted her head slightly and looked. On the steps of the restored roadhouse, in striped jackets and boater hats, a barbershop quartet was singing in old-time harmony. Their audience was a dozen or so men and boys, resplendent in buckskin and face paint and feathers, seated on folding chairs, awaiting their turn to perform.

Kate's tone was urgent. “Mary,” she whispered. “Where's Extroo â you know?”

Mary looked up slowly, hardly even looking at all. How could Mary be so casual? What was wrong with her?

“Kate, dear. I think we'd better get you inside.”

Kate let her head fall back. Would

no one

understand?

“Never mind, dear. Just be quiet and relax. Put this arm around my neck. Here, like this.”

Museum visitors, licking the special maple-sugar-on-a-stick treat created for the occasion, barely stopped to wonder why the woman in the cow-milking display sat slumped with her head between her knees. They assumed the figure had fallen on hard times and averted their eyes, the more conscientious vowing to drop something in the museum donation box on the way out.

“It was the only chair I could find in the whole bloody place!” Mary replied, when challenged later by Kate on this. “Just be glad it had three legs and not one. You don't let me stop playing doctor for a minute, do you, girl? Jeezus.”

Kate laughed and hugged her friend. “You're an angel, Mary. I don't know how I'd survive without you.”

“Neither do I, frankly.”

But something wasn't sitting right with Kate. She'd never liked snakes, true. But fainting? That was too much. She ferreted wildly around in the shambles that passed for her memory. She was walking along with Mary ⦠glanced to the right ⦠saw the hippy-ish, painted truck, the words

EXTRAORDINARY WAYNE

etc. looping through the design ⦠a man with his back turned ⦠the writhing snake â¦

Okay, okay, rewind.

The man with his back turned

. Not particularly tall, but not short, either. Thick waves of auburn hair. A touch of grey. Well-muscled shoulders. Slightly barrelled chest.

“Mary, Mary!” said Kate.

But Mary was in a snit, bustling about, crowding out Kate's thoughts. “Just about time for you-know-what!” With extraordinary strength, Mary hauled Kate up by her armpits. “C'mon, move it, girl. You think you can walk to the field? It's just a hundred metres or so. Not too far. I should know â I've been up here more times than I want to count, scouting out every jeezus patch of clover.”

Outside, Kate squinted through the trees to where Extraordinary Wayne's truck had stood. But there was no truck, no Wayne, no snake.

What in God's name was going on?

As though holding each other up, Kate and Mary tottered along the forest path toward the open field. “I never thought I'd be so excited about a bowel movement,” Mary said, gripping Kate's arm rather tightly.

Kate wasn't listening, not to Mary at any rate, but to an urgent clop-clop of thoughts stampeding through her head: am I delusional or did I see what I thought I saw? Has obsession overtaken sanity, or is the unthinkable to be thought? And finally: which is more unthinkable â the

substantial

or trans-substantial

explanation?

She looked over at Mary, nose forward, striding confidently toward the farmer's field in anticipation of bovine bliss. Kate could see this was no time to share the vision. She would play along with dull reality for now.

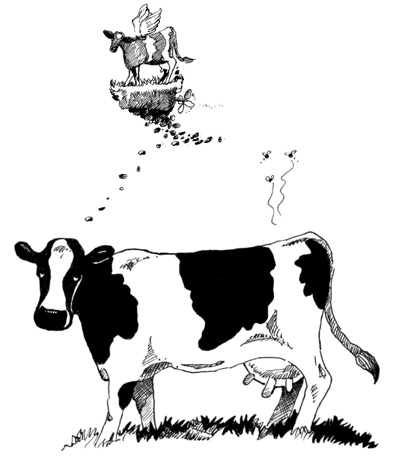

Rosie the Cow stared dumbly at the gathering crowd.

“How do they know when she's going to go?” Kate asked gamely.

“Guesswork, dear. Pure guesswork. Or maybe this is

her time

.”

“I sure hope so. I can't see this taking over from YouTube, can you?”

Twenty minutes later, nothing had happened at Rosie's south end. Many people had already wandered back to the more exciting events. Some stayed and camped out, spreading blankets or jackets on the ground and lying down in the sun. Kate and Mary sat dejected, stupid with heat and growing rather grumpy, having eaten little breakfast and no lunch. At one point, Rosie dipped her head and started to move off. Mary grew excited and gripped Kate's arm again. Kate was beginning to wonder if there'd be a bruise.

“She's heading for the clover! Kate, she's heading for the clover!”

But in the end, Rosie moved just a couple of metres, nowhere near Mary's theoretical patch of field. And still business was slow.

At about one o'clock, as Mary and Kate alternately discussed shapes in the clouds and fell to dozing, who should rush over but Leonard, more animated than Kate had ever seen him.

Mary, with accustomed physician's skill, bolted upright from deep dreaming.

“Kate! Mary! I thought it was you two. Guess what! I won! I

won the motorbike

. I've never in my life won anything! Look, look at this!”

Leonard poked at the map grid brochure the volunteers were giving out, showing the spoken-for squares on the field. The one Rosie had chosen for her business â while Kate and Mary weren't looking â was crossed over in bright red. “That's my square, right there! My dad bought me two as a present. Ever since they became citizens,” he explained, voice dripping with irony, “my parents go positively

wild

on July 1.”

Kate struggled to sitting, still woozy from her faint. Rosie the Cow was a distant blur. “What? Did we miss the big event?”

Mary grabbed Leonard's map-holding hand and brought it to her face. “That's not your square. It's mine!”

Leonard said nothing.

Mary flung Leonard's hand away and fished her ticket from a pocket. “Well, flog my knuckle-pickin' auntie, it

is

yours. Mine are right next to it. All around it!

Jeezus

. Jeezus in heaven, can't a person ever get a break in this life?”

“Congratulations, Leonard,” said Kate. “I had no idea you liked motorbikes.”

“Always wanted one. Never could justify the expense. Just in the cards, I guess.”

“More like in the clover,” Mary said, shaking her head.

“Sorry about that, Mary,” Leonard said. “You can borrow it sometimes, if you like.”

5

The Sign

“Flog my knuckle-pickin' auntie

?” Kate said on the drive home. “A Newfie expression, is it?”

“Not at all,” Mary replied. “Made it up ⦠I think. Created specially for the occasion. Though my mother was heard to say

knuckle-picker

once or twice. I gather it's got to do with yanking the stuffing right out of our lobster friends. Speaking of which, and thanks for asking, Ludmilla is doing fine. Happy as a clam.”

“Glad to hear it,” said Kate. They drove on toward town. Kate could feel skepticism burn off Mary like morning fog. “Really, I am!” Kate averred.

A while later, she said, “See that curve ahead? Could you pull off to the left there? There's a flat spot. You can pull right in.”

“What, you can't pee when we get back?”

“No. It's not that. I want to check out something. You got a couple of minutes?”

Mary said nothing, but a twitch of her mouth told Kate she was resigned. Mary slowed and wheeled them in.

“Not much to recommend the place,” said Mary, looking around.

“Let's get out,” Kate said.

The two ambled across what had once been a dirt parking lot. Here and there the sandy soil shaded into black. At the lot's verge, the forest stood tall and green and quiet.

“So, you going to enlighten me, or what?” Mary asked.

“King's Hotel, years ago.”

Mary nodded slowly. “Where your friend, uh ⦔

“Yeah.” Kate cradled her elbows in her hands as though cold, though the day was far from that. “I haven't been to this spot in years.” Was now the time to confide what she'd seen at the fun fair? No, she decided; not yet.

Mary moved toward some shade at the edge of the clearing.

“It's so ironic,” Kate said suddenly. “Here he was, finally doing something with his life. And the fact that he wasn't even in the hotel when they set it alight. He ran

into the fire

on his own steam, Mary.”

“So to speak.”

“Yeah, whatever.”

“It's not that unusual, Kate. People get killed â or near as damn â all the time, running into fires. They're trying to rescue a family member or a pet or a computer or a box of photos. I've seen the result more times than I'd care to say. When it comes to fire, people lose their minds. They don't think straight. Logically, you'd think they'd skedaddle as far and fast as they could.”

Kate grew quiet. She wandered from the edge of the clearing into the trees a bit.

“Should I avert my eyes?” Mary asked.

“I'm not going to pee, if that's what you're thinking.”

“Well I am. I'm just going to hop over behind that clump of saplings. Just be a jiffy.”

While she waited, Kate mooned about, noticing a couple of ancient-looking bits of charred wood. Then, by a rock deeper in the woods, an unusual shape caught her eye. Kate walked over and squatted down. She reached for the blackened, filthy object. It wouldn't budge, and Kate realized she would have to dig out whatever it was like a potato from the ground. This she did, with a large stone and her fingernails. When it came free, she worked the impacted soil off with a stick.

A fork. Sterling silver, if she was not mistaken. A silver fork, sitting through winter and summer, for eighteen years. The Kings' Hotel with a silver service? Kate smiled. Perhaps old man Marcotte had

contributed to his son's business more than he knew. She tucked the fork in the pocket of her shorts and headed back toward the truck.

Mary emerged from the woods carrying something large and obviously heavy, some kind of panel.

“What on earth is that?” said Kate.

“I have no idea, dear, but I'd venture to say it's authentically antique!” Groaning, Mary lugged the thing over a ditch and let it drop on the sand lot. “What do you think, besides the fact that my T-shirt is ruined?”

Kate considered the thing at their feet. A black metal door-like thing. Not a regular door, but something to be opened and closed nonetheless. A handle was still attached, as were the fittings for hinges.

“Mary,” she said. “Do you mind bringing this back with us in your truck?”

“Not a bit, dear,” Mary said. “But I'll let you do the honours lifting it in. I think I just pulled something in my back.”

Kate wanted and didn't want to know. She got whiffs of rumours: drug deal gone bad; things so dire at home he'd run away; some babe swept him off his feet. Each sliver of news held its own

frisson

. But after a while, with no definitive answer, Kate found it better not to hear or speculate. Whatever the reason, J.P. was gone. He was not coming back.

Kate's enthusiasm failed. Marks at school, which had customarily been good, fell to fair or poor â with the exception of English. For the major essay that term, meant to be a persuasive argument, she wrote a scathing satire in the style of Jonathan Swift, advocating early removal of the sexual organs of nine-tenths of the male population (one-tenth to be kept for reproduction of the species), as a solution to current social ills. These ills Kate construed as those suffered by teenage girls in particular â specifically, romantic heartbreak and unplanned pregnancy â and of the world in general, defined as gonad-driven violence and war. For this literary effort, her English teacher, Miss Brundage, let slip the exalted mark of eighty-seven from her notoriously stingy grasp. But it was the anonymous

second

marker (since it was a major essay assignment) that so stunned Kate and the rest of her class. This anonymous angel had anointed Kate's paper with the unheard-of mark of ninety-eight, giving Kate an overall average for the paper a record 94 percent. This mark in turn raised her English average high enough to win the subject medal that June.

Outside of this small victory, however, life had lost its pizzazz. Kate's weekly jazz dance class had grown stale, prompting her to quit. Finding her duties as secretary of the student council â a position she had fought for with a rather good speech to the assembled school â rather dull, she handed them over without ado to Nancy O'Brien, the girl who had disabused Kate in Grade 6 of her belief in auto-impregnation. Several friends Kate had known all her life, hurt by her lacklustre attitude, drifted beyond reach.

Nicholas kept sporadic contact, but with characteristic good manners, waited nearly a year before asking her to their final year Valentine's dance. Kate said no. And there â ah, there was the rub. Numbskull that she was, Kate said no to the dance. No, when she should have said yes.

The next day, July second, was the appointed date of Adele's visit to Nathan's grave. Kate was to pick her up at Morning Manor at ten, drive her back to the graveyard, and afterward take her into Pine Rapids for lunch, whereupon Adele would be returned to the mournful Manor in time for something called “ghoulish dinner” at five o'clock.

“Goulash?” Kate said. “Mmmm. I love goulash.”

“No dear, ghoul

ish

,” Adele corrected. Ghoulish dinner, it turned out, was Adele's droll term for the house chef's Tuesday menu consisting of skinless breast of chicken, mashed potatoes, and cauliflower, topped off with vanilla ice cream for dessert. In an email, Adele had kindly requested they go to the most “colourful” place Kate could think of for lunch. “Something green, orange or red, crunchy and vitamin-friendly would not go amiss,” she wrote.

Kate found herself looking forward to the day's arrangements â a long outing accompanied by good conversation was always a pick-me-up. She hardly dared hope other widows and widowers might request this sort of treatment; as it was, few besides Adele had sought even the most basic of Grave Concern's services. “Driving Miss Daisy” wasn't on Kate's official services list. But, depending on how the day went, Kate thought perhaps she would add it. She would have to charge for gas, of course, but as long as pickup was no more than forty minutes away, she could manage. Not only manage; enjoy. Tendering occasional grave visits might even give her an edge on the competition.

At five to ten, Kate pulled into a parking stall at Morning Manor. At three minutes to the hour, Kate handed the receptionist a stack of Grave Concern business cards. By five past, her walker folded and stowed in the trunk, Adele was tucked into the passenger seat and chatting amiably about the weather.

With no more to be said on that subject, Adele turned to Kate and said, “Kate Smithers. You're Molly's daughter, yes?”

“Yes, that's right,” said Kate. “You remember me?”

“Oh yes, I remember you, dear. Right from when you were a baby, you always had the most beautiful eyes.”

“Well, thank you. You knew me as a baby?”

“Oh yes, dear. Your mother and I go â

went â

way back. She was a few years younger than I, but oh yes, we worked together for a couple of years.”

“I never knew she worked! She never said. I always thought she went straight from school into marriage. But she never spoke about that time much.”

“Yes, your mother and I worked side by side for the Bell Telephones, down here at the exchange.” Adele nodded her head in such a way as to suggest the exchange still stood just down the road. “We were what they called âoperators.' ”

Kate smiled. Did Adele really think Kate young enough to not know what an operator was? “

Operators!

My mother?”

“Yes, here in town. In Valleyview. You know, this town was a kind of hub in those days. Logging, the whole timber trade. Well, you know. I'm sure they taught you all about it in school. And it was still going on to some extent even when you were young, Kate. Men worked in the lumbering, and the women, well, any with a job, they worked at the telephone exchange. It was a going concern, all right. We covered a large area, up and down the valley, and east and west, too. This road we're on now was the main highway, before they built the bypass.”

Adele talked on, filling in details of the time, but Kate listened only vaguely. She was stunned. As far as she knew, her mother had come straight from Toronto to Pine Rapids after school. She had met Kate's father, gotten married, had Kate â end of story. Of course! A large chunk of her mother's life was missing. How had Kate been so blind?

She thought back. As a child, she had heard things in reference to her parentsâ“May/December,” for instance. She hadn't understood the metaphor, but the words had sounded nice. Fresh, like the changing seasons. “Back door romance” was another phrase she'd overheard. Again, incomprehensible, but glamorous, or so she'd thought. “One lucky girl” Kate

had

understood, and heartily agreed with. Young Kate had indeed considered herself lucky.

Now, forty-some years on, it occurred to Kate that the “lucky girl” subject of hearsay had been not Kate herself but her mother, Molly. An eccentric idea, but there it was, shot through Kate's dull, middle-aged head like a joke shop fake plastic arrow you couldn't resist trying on.