Grow a Sustainable Diet: Planning and Growing to Feed Ourselves and the Earth (16 page)

Read Grow a Sustainable Diet: Planning and Growing to Feed Ourselves and the Earth Online

Authors: Cindy Conner

Tags: #Gardening, #Organic, #Techniques, #Technology & Engineering, #Agriculture, #Sustainable Agriculture

Mississippi Silver cowpeas and Bloody Butcher corn in the garden.

Corn sheller in action.

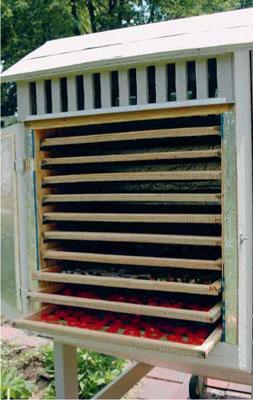

Solar food dryers in the garden.

Inside of solar dryer based on SunWorks design.

Inside of solar dryer based on Appalachian State University design.

Rotations and Sample Garden Maps

N

OW THAT YOU HAVE AN IDEA

when things are going to be in the garden beds, it might be a good time to fill in the crops on your garden map. It would be easy to just decide where your crops go according to height — short ones on the south side and tall ones in the back. I’ve seen some plans like that and I am always left wondering — but what about next year? As far as I’m concerned, garden maps need to show rotation arrows. These are arrows that show where the crops in one bed move to the next year. A garden growing a sustainable diet will have something growing in each bed all twelve months of the year. It is particularly important to make sure the cover crop that is planted in the fall is the crop you want in that bed in the spring.

Height is still a consideration, but when the sun is high in the sky during the summer months, it may not be as much of a problem as you might think. Observe how much of a shadow your tall crops cast at different times during the growing year. My solar food dryers are on the northwest side of a large maple tree. They get plenty of sun until September when the shadow from that tree extends to the dryers. That’s when I move them. If a sun-loving crop were in that spot it would be fine, as long as it was harvested by early September.

You will want a tight rotation. By tight rotation, I mean that when one crop is harvested, the bed is amended with compost and anything else it needs, and the next crop is planted without delay. The easiest way to accomplish that is to have it all decided ahead of time and shown on your garden map. You will know what is planted where and when, and would have bought the seeds well in advance. I will be talking about seeds in

Chapter 9

.

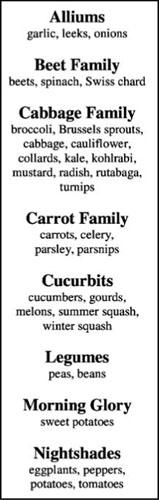

In deciding where everything goes, it is important to not plant crops in the same place they were the year before. Different crops require different things from the soil. If you planted everything in the same place every year, the soil would become depleted of certain nutrients. You can fertilize, but moving things around is a more balanced approach. That is, in addition to having your soil tested and adding any organic amendments, of course. Also, if you plant things in the same place each year, pests and diseases will accumulate. The pests know just where their favorite crops are and use those spots to raise their young, with the assurance that food will be there when they need it. There is no break in the disease cycle, either. You can fix that by rotating your crops — not planting them in the same places each year. In fact, you want to avoid planting anything in the same family there for the next couple years. With that said, I do have to mention that many sources recommend that tomatoes can stay put year after year. Whoever recommends that must not live in Virginia. With our hot humid summers, there are many tomato diseases here and I rotate my tomatoes each year. I’ve provided a list of some common crops and their kin, so you know which ones are related.

Figure 8.1. Crop Families

There are more things to know than simply not planting the same crop family in a bed. Legumes — peas and beans — leave behind some nitrogen for the next crop, so they might be followed by crops that are a little hungrier for nitrogen than others. If you have mulched a crop, the mulch will have discouraged weeds, leaving a cleaner seedbed for the next crop. It might be advantageous to plant something like carrots in that bed next.

In

The New Self-Sufficient Gardener

, Seymour divides his garden into four sections with groups of crops divided as (1) Miscellaneous,

(2) Roots, (3) Potatoes, and (4) Peas, Beans, and Brassicas. The crops in each section rotate to the next spot each year. In

New Organic Grower

, Eliot Coleman has an excellent chapter explaining rotations with an eight year plan. His plan inspired Pam Dawling to make a ten year plan and put it on a pinwheel. You can read about that in

Sustainable Market Farming

. If you are like me, you never have the one perfect plan. You work out rotations and that plan may do you well for a few years; then you decide to grow more or less of something or throw some new crops into the mix. If you understand how it all works, it will be easier making adjustments.

In my garden I had grown peanuts after wheat and rye for years. The grain harvest finished just in time to get the peanuts in. I thought that, since peanuts were legumes, it didn’t really matter what preceded them. I started to stay away from following grains with peanuts because the grain beds attracted voles, which are my biggest garden pest. One year, when I planted peanuts in a bed after garlic and onions, the half that was planted after the onions did considerably better than the half that followed the garlic. At first I thought I had planted two different varieties, but I hadn’t. I checked my garden records and realized that the onions, which were planted from sets in the spring, had followed Austrian winter peas. The garlic was in there since the fall. I adjusted my garden plan, and that fall I planted Austrian winter peas in a bed where peanuts would go the following year. My yield that next year was almost three times in that bed compared to the peanut crop following a bed of kale, onions, and garlic. When you are in your garden, make it a practice to notice little things like that. Write it down and find out what happened. It only took a glance at my garden map to realize the difference in the onion half of the bed. I could immediately see that there had been Austrian winter peas before the onions. Then I vaguely remembered reading about a legume cover crop before peanuts, which is also a legume, so I checked

How to Grow Vegetables & Fruits by the Organic Method

, my favorite reference book. That book actually suggests two soil building crops before peanuts. Okay, so there goes the guideline about not following with the same crop family. I had avoided legumes before peanuts for just that reason. Now I know better. Become a student of your own garden and let it teach you.

Read all you can and make a list of guidelines you come across. You might keep that list in your garden notebook so you’ll know where it is. At the same time, begin a list of guidelines drawn from your own experience in your garden. The companion planting charts list potatoes and cabbage as friends. Since the voles cause problems for me, I thought planting potatoes with cabbage might offer some protection. Not a chance. The voles took out the potatoes every time I tried that. I had also tried oilseed radish as a cover crop before potatoes, thinking it would offer an early fertile seedbed for the potatoes in the spring. That’s when it really hit me how much the voles like to hang around the cabbage family plants. There were vole holes galore, just waiting for my potatoes. One item on my personal list of guidelines is to keep the potatoes away from the cabbage family. If you don’t have any problems with voles, potatoes and cabbage might just work well for you.

I map out my beds with arrows to show how they will rotate. The examples of garden maps with crops, complete with the times they will be in the beds, are here to get you started thinking about how you can plan your garden. I will explain my reasoning behind the choices, how I would manage the cover crops, and give suggestions for variations on what is presented. When trying to decide how much space to give everything, it helps to map it out on graph paper. You can find suggested spacing in the seed catalogs, on the seed packets you buy in the store, and in

How To Grow More Vegetables.

The more intensively you plant, the more important it is to make sure your beds have enough fertility and that you provide enough water if rainfall is lacking. The dates on these maps are based on the frost dates in Zone 7 — last frost April 25 and first frost October 15. The Plant/Harvest Schedule (

Figure 7.2

) will help you determine the times to plant in your area.

The three bed garden in

Figure 8.2

is called the Transition Garden because it shows a garden with crops most people are already comfortable with, plus some new ones and cover crops. It combines what you already know with growing staple crops. The spacing of the main summer crops is shown in detail. What you see is the beds with what they contain for the calendar year. The rye and hairy vetch cover crop in Bed 1 was planted the previous fall when the combination of crops that have now rotated to Bed 3 were in Bed 1, leaving the rye and hairy vetch to overwinter there. In this plan the rye/vetch cover crop is cut and left to lie on the ground as mulch on about May 7, or when the rye is shedding pollen. The vetch would be flowering by then. Vetch can get pretty rangy and tangle in the rye. I only use these crops in combination if I’m going to be cutting them early like this. If I was to leave the rye go to seed, I would have planted Austrian winter peas as the legume and pulled out the winter pea plants for compost material when they flowered, at least a month before the time to harvest the rye seed. In this case, it doesn’t matter. I like vetch before tomatoes and sometimes plant only vetch as the cover crop preceding tomatoes. The legumes don’t have the heavy root system that the grains do, so when they are cut, the bed is friable and ready for planting the next crop. I always leave the roots right there in the soil. With the grains cut at pollen shed like this, you need to wait two weeks for the roots to start decomposing before you can transplant into the bed. Even then, it would be transplants only. The grain bed, cut at this time, is not ready for seeds even two weeks later. If hairy vetch was the only cover crop, I could transplant the tomatoes the same day I cut the vetch, leaving the vetch as mulch. The legumes don’t have as much carbon, thus don’t have the staying power as a mulch that the grain crops do. You see the date I cut the rye/vetch as (5/7) because it is not ready for the next crop yet. May 21 is the date the bed is ready for transplanting.