Growing Pains

Authors: Emily Carr

Tags: #_NB_fixed, #_rt_yes, #Art, #Artists, #Biography & Autobiography, #Canadian, #History, #tpl

GR WING PAINS

WING PAINS

Emily Carr,

Cedar,

1942, oil on canvas, Vancouver Art Gallery Collection, Emily Carr Trust,

VAG

42.3.28. Photo by Trevor Mills

WING PAINS

WING PAINSTHE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF EMILY CARR

EMILY CARR

FOREWORD BY IRA DILWORTH

INTRODUCTION BY ROBIN LAURENCE

Copyright © 2005 by Douglas & McIntyre

Text of

Growing Pains

copyright © 2005 by John Inglis,

Estate of Emily Carr

05 06 07 08 09 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright licence, visit

www.accesscopyright.ca

or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

First published in 1946 by Oxford University Press

Douglas & McIntyre Ltd.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver, British Columbia

Canada

V5T 4S7

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Carr, Emily, 1871–1945.

Growing pains : the autobiography / by Emily Carr ; introduction

by Robin Laurence ; preface by Ira Dilworth.

ISBN

1-55365-083-2

1. Carr, Emily, 1871–1945. 2. Painters—Canada—Biography. I. Title.

ND249.C3A2 2005

e 759.11

C

2004-906462-2

Library of Congress information is available upon request

Editing by Saeko Usukawa

Cover and text design by Ingrid Paulson

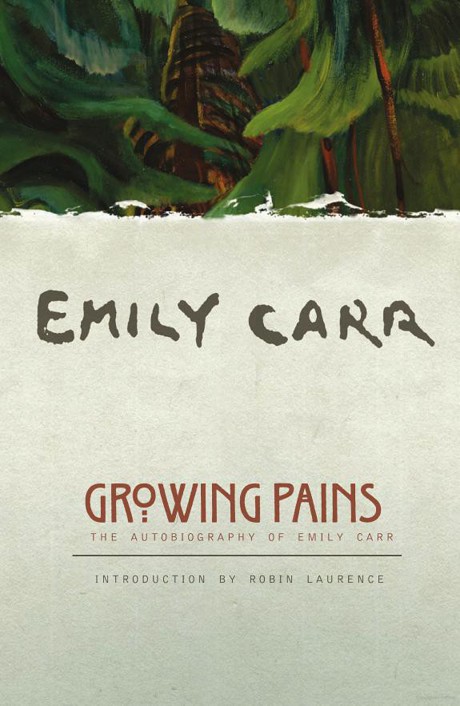

Cover painting: detail from Emily Carr,

Cedar,

1942, oil on canvas,

Vancouver Art Gallery Collection, Emily Carr Trust,

VAG

42.3.28.

Photo by Trevor Mills

Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens

Printed on acid-free, forest-friendly (100 per cent

post-consumer recycled) paper, processed chlorine-free

Distributed in the U.S. by Publishers Group West

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (

BPIDP

) for our publishing activities.

NOTE

: About a thousand words were deleted from “The Mansion” after the first edition of

Growing Pains

; they have been restored.

To Lawren Harris

INTRODUCTION: THE MAKING OF AN ARTIST

by Robin Laurence

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN NUDE AND NAKED

WESTMINSTER ABBEY—ARCHITECTURAL MUSEUM

LEAVING MISS GREEN’S—VINCENT SQUARE

PAIN AND MRS. RADCLIFFE—THE VICARAGE

KICKING THE REGENT STREET SHOE-MAN

THE RADCLIFFES’ ART AND DISTRICT VISITING

SEVENTIETH BIRTHDAY AND A KISS FOR CANADA

:

THE MAKING OF AN ARTIST

by Robin Laurence

OVER THE PAST

few decades, Emily Carr’s reputation has soared so high that it now can be argued she is Canada’s best-known artist, historic or contemporary. Her impassioned paintings of the West Coast of Canada—her depictions of the monumental sculpture of British Columbia’s indigenous peoples and of the towering trees and dense undergrowth of the region’s rain forests, executed during the early decades of the twentieth century—have superseded even the Group of Seven’s iconic claim to Canadian wilderness. And to national identity. Yet it is not simply Carr’s images that speak to us but also the story behind them. The romantic striving to manifest her vision, through decades of adversity, informs her work and amplifies our interest. We are moved by her struggle to survive economically and creatively, and to discover a way of expressing herself that accords with her sense of who she is and what her subject must be. We see not only aesthetic and thematic accomplishment in her work but also the difficult journey towards overcoming the gender and social biases of her time and place. We see the final realization of the artist she always knew herself to be.

We also see an artist to whom we can attach our own relationship to place, an artist whose legend haunts the West Coast landscape and shapes our understanding of it. An artist who confounds our expectations, too. When I was a graduate student of art history, I lived in the James Bay district of Victoria, across the street from the last house that Emily Carr occupied. The little blue cottage that belonged to her sister Alice was the final place to which the artist laid claim before checking herself into a nursing home to die. When I was a student, I was moved by the story of Emily Carr’s last days and weeks—she was said to have walked across the street to telephone for an ambulance—and by all the other stories told about her in the neighbourhood, her neighbourhood, the one in which she was born and raised and lived the majority of her seventy-three years.

When I was that person, young and green and casting around for a thesis topic, I looked at the indigenous art of the Northwest Coast, looked at Emily Carr’s mature paintings, and knowing a little about both but not a lot about either, I was certain the painting style had been influenced directly by the carvings they depicted. I could see so many formal similarities: the sinuous lines and organic forms, the volumetric handling of space, the smooth and graceful transitions from plane to plane. And then there was her own claim, made in the pages of this book: “Indian art broadened my seeing.” Only later did I come to understand that there was more Paul Cézanne than Charles Edenshaw in her treatments of carved poles and primordial forests. There was more European modernism percolated through the Group of Seven than revelation directly acquired from the hands of classic Haida or Kwakwaka’wakw artists. Only later did I learn that Carr needed the direction of her white male teachers and colleagues

to find a way through First Nations art—and then past it to her own understanding of the landscape. The paradox is unsettling: so much of Carr’s struggle seemed to be in throwing off the dictates of the conservative and patriarchal society into which she was born; so much of her mature accomplishment involved the advice and encouragement of men.

Born in Victoria, British Columbia, in 1871, Carr had to leave what was then a cultural backwater to study art with the seriousness her calling demanded. Over the course of twenty-one years, between the ages of eighteen and thirty-nine, she took herself to San Francisco, to London and to Paris in order to equip herself to be an artist. It was not until she was in her mid-fifties, however, living again in conservative Victoria, poor, alienated, at times despairing, that she made the connections with the Group of Seven, and with Lawren Harris particularly, that catapulted her into becoming the artist we now recognize as Emily Carr. The astonishing thing about her career is that the most definitive part of it—the part upon which her reputation is based—occurred when she was in her late fifties and early sixties. Hers was a long and uncomfortable apprenticeship.