Growing Up Laughing: My Story and the Story of Funny (17 page)

Read Growing Up Laughing: My Story and the Story of Funny Online

Authors: Marlo Thomas

Marlo:

Did your daughter, Melissa, ever get mad at you for making jokes about her in your act when she was younger?

Joan:

She was never the butt of my jokes. Same with Edgar. I made myself the butt of

their

jokes.

Marlo:

Like?

Joan:

Like, “On my wedding night I came out of the bathroom and Edgar said, ‘Let me help you with the buttons,’ and I said, ‘I’m naked.’ ” It always came back on me.

Marlo:

Your whole career—your life—is about being a survivor.

Joan:

It’s mountain after mountain, Marlo. And the mountain at this moment is the age thing, and staying relevant.

Marlo:

Do you think you’ll do a book on aging now?

Joan:

I don’t know—I still don’t feel old. But people say to me, “You should really think about selling your apartment.” I say, “Are you crazy?” And then I think,

What would I tell a seventy-six-year-old woman? I would say, “Sell your apartment.”

Marlo:

Will you?

Joan:

Probably, because my life has changed.

Marlo:

And will that new life sit well with Joan Rivers, lion tamer?

Joan:

It will be fine. Cindy Adams, Barbara Walters and I have talked about this. We want to live at the Pierre Hotel, have three apartments on the same floor—and share one nurse. It’s our dream.

Marlo:

What a dream.

Joan:

And we’ll have one person to walk all of our dogs. We’ll have a very good time.

T

he saying goes, “Dying is easy, comedy is hard.” I think that’s what makes comedy such an obsession. And you have to be an obsessive to work in it. Fixing, honing, scratching out. You know it when you hear it. And until you can hear it, you can’t stop.

I remember when we were shooting the pilot of

That Girl,

I was going over lines in the script, working through each scene to be sure we’d covered everything. Our director, Jerry Paris, looked at me, amused.

“What is it with you?” he said. “Every scene is opening night?”

“Yes,” I said, incredulous. “Isn’t it with you?”

But it

was

with Bill Persky, who was a co-creator of the series, along with his writing partner, Sam Denoff. As the Executive Producer I worked closely with both of them, but I had an immediate bond with Billy. He liked women, and was one of the first men I’d ever worked with who had no problem having a woman as a boss (even one in her twenties). There weren’t a lot of guys who did. Lucille Ball was our landlord at Desilu Studios, where we rented our soundstage. She had real power—she owned the studio. Tony told me years later that, whenever someone was looking for me, the joke was “She’s having a meeting in the men’s room with Lucy.” That was the climate in the late Sixties, which made Billy unusual. He really seemed to understand the feelings of a young woman. He had grown up with a sister and had three daughters. So he got it.

I depended on Billy a great deal during the first year of the show, and we quickly became friends. One day he developed serious muscle spasms in his neck—obsessiveness can do that to you—and was confined to his bed by his doctors. I was worried about him, and worried about how the show would proceed without him.

At the table with Billy Persky—on the same side, in more ways than one.

Billy loves to tell the story of my coming to his house to discuss some trouble we were having with the script we were about to shoot. There he was in traction, lying absolutely flat on his back with a nine-pound weight pulling on his head. He couldn’t see anything but the ceiling, so he had to wear a special pair of glasses that were actually mirrored cubes, cut diagonally so that he could see down even though he was looking up—kind of like a periscope. But since he couldn’t move his head, he could only see me when I was directly in front of him.

Undaunted, I paced back and forth at the foot of his bed, passionately laying out the script’s problems, oblivious to the fact that he was flat on his back—and oblivious to the mirror’s limited range of vision. Billy could barely move, but he desperately tried to follow me with his eyes as I darted back and forth in his mirrored glasses. At one point he moved his head to try to catch my fleeting image, and winced in pain. I felt terrible, so I sat on his bed to comfort him—which caused the mattress to depress and him along with it, as the weight stayed stationary, almost pulling his head off. Then we burst into uncontrollable giggling at the absurdity of the situation. We were obviously made for each other.

A few months later, I was in the makeup room at the studio, about to begin the day’s work. I took a brush to my hair and, after a few strokes, I froze in pain. I couldn’t get my arm to come down. I had my own muscle spasm, and ended up in a similar hospital bed and neck brace.

My father came to visit me. He walked into the room, stood at the foot of the bed and said, “If you live, you’ll be a big star.” Then he lectured me on pacing myself.

Now he tells me.

FOR THE SECOND YEAR

of

That Girl,

we had the great fortune of getting Danny Arnold to produce the show. Danny had produced the first year of

Bewitched,

and would later create a hit show of his own,

Barney Miller

. He was superb at everything—writing, directing, editing, producing—and was the ultimate obsessive. I felt like I had died and gone to heaven. I would leave the studio at 9:30

P.M.

after a day of shooting—having first arrived that morning at 5

A.M.

—and I would see the lights on in the editing room and know Danny was still there. A man like that makes an obsessive like me sleep like a baby. Someone was minding the store.

Danny did so many great things for me. One of them was to bring in a female story editor, Ruth Brooks Flippen. Until Ruth joined our all-male staff, I had felt like a lonely voice in the wilderness, constantly explaining,

But a girl wouldn’t say that to her father . . . or her boyfriend . . . or her best friend . . .

I had always known that, for a woman, there was safety in numbers. It’s never wise to be the only female at the table. Experience had taught me: One is a pest, two is a team, three is a coalition. Now I had Ruth. We were only two but, together, we were like the Red Army.

I remember one late night we were leaving the office of one of our writers, who had been moaning about how hard we were being on him.

“Why do some men always make you feel like you’ve beaten them up just because you don’t agree with their opinion?” I asked.

“I know what you mean,” Ruth said. “All I’ve ever really wanted was a good cry, but my husband always beats me to it.”

I loved her—she always nailed it.

And I was learning that, even for a woman with power, the path was dotted with land mines—

she’s so ambitious, she’s so aggressive, she’s ruthless.

“Funny thing,” I used to say, “a man has to be Joe McCarthy to be called ruthless . . . all a woman has to do is put you on hold.”

After the series ended, I went to New York to study acting with Lee Strasberg, and learned a whole new way to work. It became my true obsession—I felt like I had found a home. Strasberg wanted all you had to give. He welcomed it.

When I had my first meeting with Lee, he asked me why I wanted to study with him after having had such success in television.

“Because I’ve gone a long way on charm and a natural comic ability,” I said. “I want to learn how to work deeper.”

“Don’t look a gift horse in the mouth,” Lee said. I loved him for that. I had heard he was a stern man, even mean, but that’s not the man I met that day. I told him that I really loved comedy and wanted to work on a comedy scene in his class. He said no—no comedy scenes. I wouldn’t understand why until much later. I would learn that the sense of truth that was at the heart of the dramatic work would

feed

the truth of the comedy.

My father teased me. “Call me when they have the class on comedy timing,” he said. “I want to attend.”

BUT I WAS

still a bit intimidated by Lee because of his reputation, and I felt that everyone in the class knew the work—but me. I didn’t want to make a fool of myself (

look who’s a TV star!

), so it took me six months to stop hiding in the back row and come forward.

When I finally got up to do my first scene in front of the class, Lee’s eyes twinkled.

“Well, welcome,” he said, and then he announced the scene as he always did. “This scene is from

The Gentle People,

by Irwin Shaw.” But I was so nervous that his voice sounded like it was coming from a great distance and through a filter. I thought,

How unfortunate to lose my hearing the day I do my first scene for Lee Strasberg.

Fear does play its tricks.

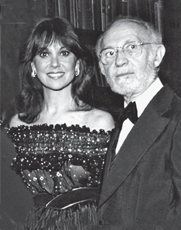

With Lee at a black tie gala. While everyone hobnobbed, he hung out with the waiters. He could spot from across the room that they were aspiring actors.

But once I got that first scary day behind me, I couldn’t wait to do more. And I did

three years

more. I only wish Lee could have lived to see me portray a schizophrenic in

Nobody’s Child

. I never would have gotten near playing that kind of part without Lee’s exercises, and the subsequent work I did and continue to do with his primary disciple, the brilliant Sandra Seacat.

On the set of

Nobody’s Child

with two of my favorite obsessives: Tom Case (my makeup artist of 40 years) and my acting coach Sandra Seacat (who was emoting).

Sometimes two obsessives don’t make a right—and it didn’t with me and my guy at the time, Herb Gardner. Herbie was a wonderful playwright, a funny man and a true original. But when it came to work, there was only one way—his. And there was no talking him out of his position.

Herbie wrote a play for me called

Thieves

. He even wrapped it in a box tied up with a ribbon and gave it to me for my birthday. What a deeply romantic and loving man he was. But when Herbie and I started to talk about the play, I questioned the ending, which I thought went awry. Herbie became furious. We argued so much about it that I finally said, “Let’s not do this. It’s going to be the play or us. We all won’t survive.”

So I backed away, and the part was given to Lily Tomlin. Soon after, Lily had a conflict and had to pull out, and Valerie Harper was cast, with Michael Bennett directing.

The play wasn’t received well in its Boston tryout, and the producers canceled the New York opening. Herbie was heartbroken—three years of work, and it was over. Just like that. Welcome to show business.

A few nights after the opening, some good friends of Herbie’s flew in to be with him in Boston. I had been on the road promoting

Free to Be . . . You and Me

and had flown in with Chuck Grodin. We were all at a restaurant after the show—producers Norman Lear and David Picker; Frank Yablans, the head of Paramount who was backing the play; Chuck and me. After a while, Frank came up with the idea that if I stepped into the lead role, and Chuck redirected the play, Paramount would put in some more cash, and maybe we’d all just pull it off. Herbie, Norman and David enthusiastically agreed. Chuck and I were stunned. We had just come to

see

the show. It felt like a set-up, but what could we do? We both loved Herbie and didn’t want to see his work die in Boston. Only problem was, we’d have just four days in which to do it. The perfect scenario for a pack of obsessives.

I’ll never forget that opening night. Herbie and Chuck came to my dressing room before the show to give me a pep talk and burst out laughing when they saw the expression on my face. I looked like a trapped rabbit. I wasn’t entirely sure of my lines, and I had no idea where to make my entrances in the complicated, multilevel set. It was the classic actor’s nightmare of being totally unprepared. Only it was really happening.

When the curtain went up, I was lying in a bed and I could feel my heart pounding. It felt like it was banging through the mattress.

Oh my God,

I thought.

I’m going to have a heart attack on stage.