Growing Up Laughing: My Story and the Story of Funny (24 page)

Read Growing Up Laughing: My Story and the Story of Funny Online

Authors: Marlo Thomas

How do you not love this guy?

It was too late to call off the party, so we decided that I would phone the party and tell my story to the assembled guests. There were a lot of obsessives there that night—so they got it. Phil said it was a great evening. I wish I had been there.

As disappointed as I was to miss the party, the sacrifice paid off. The work sessions with Stephen were thoroughly successful, and he quickly turned out a vibrant score. One melody was so beautiful, and Phil was so charmed by it, that he shipped the sheet music to a company in Switzerland and had it made into a music box as a gift for me—in time for Christmas. Obsessives were

everywhere

.

OUR MOVIE,

which we renamed

It Happened One Christmas,

aired on ABC two weeks before Christmas. It got an incredible 46 share of the audience, and played for four successive seasons after that—just as Freddie had wanted. Some critics were abashed that I had monkeyed with the gender in a Capra film, some thought it ingenious. But most important, the audience took the film’s message to heart as passionately as they had with the original. And the mail we received was all about Capra. So I guess he was part of our movie, after all.

A few months later, Orson Welles was a guest on

The Tonight Show

.

“So you appeared in a movie with Marlo Thomas as the producer,” Johnny Carson said to him. “What was that like?”

“She’s an interesting woman,” “Orson answered. “She’s a cross between St. Theresa of the Flowers and Attila the Hun.”

All comedy buffs think they’re the one who discovered Steven Wright. And once we’ve made that discovery, it’s hard to let go of him. He’s addictive—hear one Wright joke and you need to hear another. There have been other comedians who built their acts on a string of one-liners, but Wright’s are different. More than just zingers, each line tells a miniature story—at first bizarre, then eye-opening, then finally brilliant, as we get a deeper, funnier look at the things we thought we knew.

—M.T.

“I like to reminisce with people I don’t know.”

—Steven Wright

M

arlo:

You know, preparing for this interview wasn’t so easy. Your bio on your website was about as short as your jokes. The whole thing is twenty-eight words—twenty-six if you don’t count “The End.” Why? Don’t you want anyone to know about you?

Steven:

Well, my publicist wrote this really long biography of all the stuff I had done, and I felt self-conscious about it, like I was making a speech about myself. So I made a smaller version. I didn’t do it to be mysterious. The other one just seemed too self-centered.

Marlo:

Well, that’s sort of what a biography is, you know? There are a lot of them on Winston Churchill, like twenty-seven volumes. He must have been a very self-centered man.

Steven:

Yeah. That’s hilarious.

“I remember when the candle shop burned down.

Everyone stood around singing ‘Happy Birthday.’ ”

—Steven Wright

Marlo:

You can say in one sentence what it takes most comics to say in a paragraph. Your one-liners are like gold. How many rough drafts do you go through to get it so perfect?

Steven:

Something in my mind starts to edit down the joke so I can get the point across with the fewest amount of words. I don’t like standing there if they’re not laughing. I don’t like doing big, long set-ups.

Marlo:

It’s so economical, what you do. You take us from the beginning to the end in such a short amount of time. And you embrace the absurdity of life. If the world were more normal, would you be out of work?

Steven:

Probably. There are so many weird things in life—from the time you wake up till the moment you go to sleep. So many pieces of information go by, and some of it just jumps out at me as a joke.

Marlo:

How many of these lines do you do in a typical show—like eighty?

Steven:

A typical ninety-minute show has a couple hundred lines, probably.

Marlo:

Wow.

Steven:

To do a five-minute thing on

The Tonight Show,

that would be about twenty, twenty-two jokes.

“I had a friend who was a clown.

When he died, all his friends went to the funeral in one car.”

—Steven Wright

Marlo:

What’s the longest Steven Wright joke on record?

Steven:

It was a pretty traditional story.

Marlo:

Tell it to me.

Steven:

I was on a bus and I started talking to this blond Chinese girl and she said, “Hello,” and I said, “Hello, isn’t it an amazing day?” And she said, “Yes, I guess.” And I said, “What do you mean, ‘I guess’?” And she said, “Well, things haven’t been going too well for me lately.” I said, “Why?” She said, “I can’t tell you. I don’t even know you.” And I said, “Yeah, but sometimes it’s good to tell your problems to a total stranger on a bus.” And she said, “Well, I’ve just come back from my analyst and he’s still unable to help me.” And I said, “What’s the problem?” And she said, “I’m a nymphomaniac, and I only get turned on by Jewish cowboys.” Then she said, “By the way, my name is Diane.” And I said, “Hello, Diane, I’m Bucky Goldstein.”

That’s, by far, the longest joke I’ve ever done. It was worth it because the laugh was huge. I did it so many times, I kind of retired it.

“It was the first time I was in love and I learned a lot.

Before that I never even thought about killing myself.”

—Steven Wright

Marlo:

People always call you deadpan. How did that start?

Steven:

It was an accident. I was so afraid of being on stage that I’d talk very seriously, even though I was saying these insane things. I was concentrating so hard on trying to say them in the correct way, and in the correct order, that it came out deadpan. And that became my trademark.

Marlo:

You don’t ever appear nervous. I mean, when I’m nervous, I talk as fast as possible. How did you keep that kind of unflappable calm?

Steven:

A friend of mine gave me some good advice when I would do

The Tonight Show

. I would be so nervous that I’d almost get, like, numb. So my friend told me to play the studio audience like I was playing in a little club. There were 500 people in the studio, so I just ignored the idea that it was going out on TV. And once they started laughing, it became just like in the clubs. If you stop to think that 10 million people are watching you, you’d get so nervous you couldn’t even function.

“I was reading the dictionary.

I thought it was a poem about everything.”

—Steven Wright

Marlo:

How did it all start for you?

Steven:

From TV. I have two brothers and one sister. My brother controlled the television because he was older, so I had to watch what he watched. And I liked it—Johnny Carson’s monologue, and all the comedians he had on, like Robert Klein, David Brenner and George Carlin.

Also, there was a radio show in Boston every Sunday night. The host played two entire comedy albums, and I kept a little radio in bed with me. I guess I was studying it all without knowing I was studying. I loved Woody Allen the best. I also loved Bob Newhart’s albums and Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks’s

2000-Year-Old Man

. By the time I was sixteen, it was my fantasy to be doing this.

Marlo:

But your work is so different from theirs. How did you find your style?

Steven:

I started listening to the way Woody Allen structured jokes. Then I got into surrealistic painting. I loved the way the artists combined different realities that couldn’t be combined in the real world. Years later, when I started writing jokes, I did the same kind of thing.

Marlo:

That’s really interesting. Sid Caesar and other comics have talked about comedy in terms of music, but no one has talked about it in terms of painting.

Steven:

Well, I’ve always been very visually stimulated. Drawing helps my comedy, because when you draw something, you examine it in a much closer way. Like, if you’re drawing a table that has a wine bottle on it, and a wineglass beside the bottle, not only do you see the glass and the bottle, you also see the shape in between them. Exercising that part of my mind helped me with my comedy, because it taught me to notice things more closely than I normally would.

“I went to the museum where they had all the heads and arms

from the statues that are in all the other museums.”

—Steven Wright

Marlo:

Were you the funny guy in school?

Steven:

I was always joking around with my buddies and making them laugh. I wouldn’t make the whole class laugh, because I was a shy kid and didn’t want the attention.

Marlo:

What’s a Steven Wright joke, circa junior high?

Steven:

I made up a joke that made my friends laugh, about a flock of false teeth. I remember thinking that, even though there was no such thing, the words were assembled in a funny way.

Marlo:

So what did your flock of false teeth do?

Steven:

I have no idea. Just fly by, I guess . . .

“I was at my uncle’s funeral and I was looking at the coffin and

thinking about my flashlight and the batteries in my flashlight. And I

told my aunt, ‘Maybe he’s not dead, he’s just in the wrong way.’ ”

—Steven Wright

Marlo:

Okay, so here’s this kid in school who knows he’s funny, and has his own craft. What was your first professional gig like?

Steven:

When I did my first open mike, I tried about three minutes of jokes, and the audience laughed at, like, half of it. I thought it was a failure because they didn’t laugh at all of it. One of the other comedians pulled me aside and told me that I was pretty good for never having done it before.

Marlo:

After that, did you think you’d make it?

Steven:

You never know what’s going to happen. I wanted to try stand-up. I wanted to give it a shot. And I didn’t want to wonder my whole life about what would’ve happened if I had tried it. I’ve had this whole career and this whole life because I took that initial risk.

“I went to a restaurant that serves ‘breakfast at any time.’

So I ordered French Toast during the Renaissance.”

—Steven Wright

Marlo:

Last question: Have you ever owned a comb?

Steven:

Used to as a boy.

Marlo:

What happened to it?

Steven:

I think I lost it.

“I’m writing a book. I’ve got the page numbers done.”

—Steven Wright

ANOTHER STORY FROM BOB NEWHART

There was a comic who called himself Professor Backwards. His name was actually Jimmy Edmondson. In his act, people in the audience would call out their state or city, then Jimmy would instantly pronounce it backwards. He was probably dyslexic, but he made a small living from the act.

Jimmy was always hard up for funds, so during the era of person-to-person telephone calls, he figured out a way to avoid paying for calls to his agent. Whenever he needed to know when his next club date would be—and what he’d be paid—he’d speak in code to his agent, through the operator.

“Person-to-person call from Jimmy Edmondson,” the operator said on one occasion.

“He’s not in right now,” the agent answered.

“Do you know where I can reach him?” interrupted Jimmy.

“Yes, he’ll be at the Fontainebleau Hotel on January 1st through the 13th,” the agent said.

“Do you know what room he’ll be staying in?” asked Jimmy. (This was the code for how much money he’d be paid.)

“Yes, he’s in room 750,” the agent said.

“Wait!” said Jimmy. “I thought he was supposed to be in room

1500

.” To which the agent replied:

“Tell him he’s lucky he’s not in room 500 . . .”

W

here’s she gonna go?”

That’s what my uncles (all eight of them) would say whenever they had an argument with their wives. And no matter how angry those women might get with their husbands, the bottom line was: Where’s she gonna go?

Was it then? Sometimes I think it

was

then that I became a different kind of female from all the women in my family. As a girl growing up, I witnessed sixteen marriages—nine on Dad’s side, four on Mom’s, two sets of long-married grandparents, Italian and Lebanese. And, of course, my parents’ marriage. And in every one of them, the husband was

numero uno

. There wasn’t any abuse or that kind of thing. Just the everyday drip, drip of dissolving self-esteem.

I made up my mind somewhere in the middle of all this that the whole domestic scene was not for me. I had things I wanted to do and didn’t want to do.

I knew I didn’t want to give up my dreams for love and miss them for the rest of my life, like my mother.

I knew I didn’t want to be dominated by another person.

And, most important, I knew I always wanted to have a place to go. That above all. No one would ever say about me, “Where’s she gonna go?”

So when I told my mother I had fallen in love with a divorced man who lived with his four young sons, she said, “Oh, what a joke on you!” A below-the-belt punch line if there ever was one, but it still made me laugh. My mom knew a good set-up when she heard one, and my life had been the perfect set-up for that line.

Not only had I always had a fight-

and

-flee response to commitment and marriage, I was also the girl who had a stockpile of sassy remarks, like “Marriage is like living with a jailer you have to please.” And “Marriage is like a vacuum cleaner—you stick it to your ear and it sucks out all your energy and ambition.”

I was “pinned” in college, but that was the fun, romantic thing to do. And romance I liked. I also liked men—their soft, fuzzy necks, their strong legs, their firm behinds. And in the morning there was something about a man in a terry-cloth robe—I always had a strong genetic urge to start squeezing orange juice. But still . . .

My eyes were on the horizon, not on the hearth. And I actually felt betrayed by my best girlfriends as they dreamily walked down the aisle.

Hey, what about that swell loft we were gonna get together?

How ’bout that great trip to the Far East we had planned?

One by one they deserted me. Sometimes I wondered if I was the only girl in the world who felt like I did. Then I read

The Feminine Mystique

by Betty Friedan. And I knew I wasn’t.

Around this time, I was screen-tested for a TV pilot for ABC called

Two’s Company

. I was thrilled when I got the part, and the pilot was terrific. It didn’t sell. No big news—most pilots don’t sell. But the show brought me to the attention of Edgar Scherick, the head of programming for ABC. Scherick told me that he and the people from Clairol, one of the network’s prime sponsors, thought I could be a television star, and he described a few ideas they had for a show for me. In all of the shows, I’d be playing the wife of someone, or the secretary of someone, or the daughter of someone.

I hesitated for a moment, then charged ahead.

“Mr. Scherick, did you ever think about doing a show where the girl is ‘the someone’?” I asked. “You know, a girl like me—graduated from college, doesn’t want to get married and has a dream of her own.”

Scherick looked at me like I was speaking in Swahili.

“Would anyone watch a show like that?” he said. I asked him to read

The Feminine Mystique

—which he did. He was a one-of-a-kind executive. He called me after he finished the book and said, “Is this going to happen to my wife?” He was so intense he made me laugh. Then he said, “Everybody thinks I’m crazy, but I’m going to go with you on this.”

Edgar (by this time he was Edgar) was the true father of

That Girl

. And a true mentor of this one.

Despite Edgar’s support, there wasn’t a lot of enthusiasm for the premise of the show. And the research proved it. Television audiences didn’t like show business stories, they didn’t like girls without families and they didn’t much care for shows starring actors no one ever heard of.

But the night we premiered, we won our time slot. What happened? What happened was that this girl, who seemed like a revolutionary figure to the men in suits who did the research, was not a revolutionary figure at all. She was a fait accompli. There were millions of

That Girl

s in homes across America. We were not our mother’s daughters. We were a whole different breed. As Billy Persky would later proudly note, “We threw a grenade into the bunker and cleared the way for Mary Richards and Kate and Allie and everyone else to walk right in.”

Once we began taping the series, the mail started pouring in—and it was startling. We got the usual “I love your haircut” type of letter. But I was also receiving mail from desperate young females unloading their secrets.

“I’m 16 years old and I’m pregnant, and I can’t tell my father. What should I do?”

“I’m 23 years old, and have two kids, no job and a husband who hits me. What should I do?”

I didn’t expect it. I was doing a

comedy

show. But the more I read these letters, the more I realized that these young women had no one to go to but this fictional young woman they identified with on TV. They laughed with me, so they felt they knew me. I was close to their age. And I felt responsible.

So my assistants and I tried to find places of refuge for these young women. We hunted in city after city, but there weren’t any such places. This was before the term “battered wives.” Back then, it was just called “unlucky.” That mail politicized me. And as much as anything else I had witnessed in my life, it was the seed for much of what I’d put my energy toward in the years ahead.

Even though the show was doing well, the battles went on. Some at the network wanted my character to have an aunt move into her apartment with her.

“Why?” I asked.

“Because people would prefer to see a girl living in a family unit.”

“A family unit?” I countered. “

The Fugitive

doesn’t even have a city. Why do I have to have a family?”

The debates weren’t just in the executive offices. We were finding our way in the writers’ room, as well. One week, we were reading the script for the next episode, when I stopped cold at a joke. The story was about computer dating. Ann Marie sends in her picture, as does a handsome young man (played by comedian Rich Little). On the night of the big date, Ann is getting dressed when the doorbell rings. So her neighbor, Ruthie (played by Ruth Buzzi), runs to answer the door. Ruth had become famous for her funny characters on the variety show

Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In

. An audience favorite was a funny-looking biddy who was suspicious of all men and rapped them on the head with her purse.

In our script, when Ruth opens the door, Rich was to look at my picture in his hand, then at her, and mutter, “She must have gone right through the windshield.” The guys in the room thought this was very funny.

I hated that joke. It undermined everything I believed we should be saying to girls. And I didn’t want Ruth to feel insulted.

“I want to take this out,” I said.

“Why?” Ruth asked. “It’s funny.”

“It’s not funny, Ruth, it’s demeaning.”

“Hey, c’mon,” she said. “It’s my bread and butter.”

I should have known. I grew up with comedians. Phyllis Diller had made a livelihood with this kind of self-deprecating routine. The joke stayed in, but I was always uncomfortable that it was in my show.

AFTER THE FIRST

successful year of

That Girl,

an agent had the idea of my playing the part of Gloria Steinem, a young reporter who had gone undercover as a bunny at the Playboy Club and revealed what young women were being put through on the job. The agent set up a meeting to discuss the deal with Gloria and me. This would be the first time Gloria and I met.

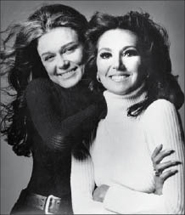

Gloria and I go glam—wind machine and all.

We sat across from the agent at his desk. He beamed appreciatively at us.

“Boy,” he said, “I don’t know which one of you I’d like to fuck first.”

Boy, did he pick the wrong two women to say that to. I don’t think we heard anything else he said that day. The meeting—and the idea—came to an immediate end. But Gloria and I were at the beginning of a long and deep friendship.

SOON AFTER,

Gloria called me and asked if I would pitch in for her at a welfare mothers event in New Hampshire.

“Welfare mothers? Are you crazy? They’ll hate me,” I said. “I’m a kid from Beverly Hills and I don’t have any children. What will I talk to them about?”

“Trust me,” Gloria said. “They’ll love you—and you’ll love them. You’re all women.”

I was terrified. But I wanted to rise to the occasion, and I think I was curious to see if these women and I would be able to connect. So I started by talking about family.

I told them about my grandmothers, and made them laugh with stories of Grandma the drummer, and how independent and eccentric she was. I told them about the time my mother had received a beautiful silver picture frame, and how she’d asked Grandma for a photograph of her to put in it. I knew what my mother wanted. She wanted a mother-like portrait of Grandma in a lovely dress and a string of pearls, her hair in a neat bun. But what Grandma sent was a picture of herself dressed as a fortune-teller—with wild scarves, gypsy earrings, a crystal ball and a mischievous grin.

Marching for the ERA in Chicago, with Bella Abzug (

IN HAT, SECOND FROM THE LEFT

), Phil, Betty Friedan (

FAR RIGHT

) and thousands of women warriors.

“This is the show woman who is your mother,” Grandma was saying. “Frame that!”

And my mother did. She put it right on the piano in our living room. When my little friends came to our house and asked me who the lady in the picture was, I didn’t even hesitate.

“That’s my mother’s fortune-teller,” I’d say.

I also talked to the welfare mothers about the other women in my family. About my mom giving up the work she loved to be with my dad. About my aunts and their marriages, and how they had been dismissed because they were women. By the end of the night, we were laughing and crying, and Gloria had opened my eyes and my heart to the connections that we women have with each other.

AND THEN I

met Bella.

Bella Abzug was a big, strong, brilliant woman. She was a lawyer and a fearless congresswoman from New York who fought for women’s rights and all the causes she believed in with a fierce sense of justice and outrage. For those of us who worked alongside her, she was both an inspiration and a mentor. Some people would describe Bella as “the one with the big hat.” They didn’t know Bella. She wore dozens of hats, and shielded all of us with her broad brim.

She also had a great sense of humor that she often used to make a political point. It was in the midst of the heated fight for the Equal Rights Amendment that she made that memorable quip: “True equality will come not when a female Einstein is recognized as quickly as a male Einstein, but when a female schlemiel is promoted as quickly as a male schlemiel.”