Grumbles from the Grave (7 page)

Read Grumbles from the Grave Online

Authors: Robert A. Heinlein,Virginia Heinlein

Tags: #Authors; American - 20th century - Correspondence, #Correspondence, #Literary Collections, #Letters, #Heinlein; Robert A - Correspondence, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #20th century, #Authors; American, #General, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Science Fiction, #American, #Literary Criticism, #Science fiction - Authorship, #Biography & Autobiography, #Authorship

But for the future. I don't know what you'll be doing. I have no idea what pressure of work will be on you. I don't know whether you can ever write a story as a method of relaxation. (I can; it's as much fun as reading someone else's work.)

December 9, 1941: Robert A. Heinlein to John W. Campbell, Jr.

This is the first time in forty-eight hours that I have been able to tear myself away from the radio long enough to think about writing a letter. Naturally, our attention has been all in one direction up to now. We are still getting used to the radical change in conditions, but our morale is extremely good, as is, I am happy to report, that of everyone. For myself, the situation, tragic as it is, comes to me as an actual relief and a solution of my own emotional problems. For the past year and a half I have been torn between two opposing points of view—and the desire to retain as long as possible my own little creature comforts and my own snug little home with the constant company of my wife and the companionship of my friends and, opposed to that, the desire to volunteer. Now all that is over, I have volunteered and have thereby surrendered my conscience (like a good Catholic) to the keeping of others.

The matter has been quite acute to me. For the last eighteen months I have often been gay and frequently much interested in what I was doing, but I have not been happy. There has been with me, night and day, a gnawing doubt as to the course I was following. I felt that there was something that I ought to be doing. I rationalized it, not too successfully, by reminding myself that the navy knew where I was, knew my abilities, and had the legal power to call on me if they wanted me. But I felt like a heel. This country has been very good to me, and the taxpayers have supported me for many years. I knew when I was sworn in, sixteen years ago, that my services and if necessary my life were at the disposal of the country; no amount of rationalization, no amount of reassurance from my friends, could still my private belief that I ought to be up and doing at this time.

I logged in at the Commandant's office as soon as I heard that Pearl Harbor was attacked. Thereafter I telephoned you. The next day (yesterday) I presented myself at San Pedro and requested a physical examination. I am an old crock in many little respects—half a dozen little chronic ailments, all of which show up at once in physical examination but which I was able to argue them out of. Nevertheless, I was rejected on two counts, as a matter of routine—the fact that I am an old lunger and that I am nearsighted beyond the limits allowed even for the staff corps. They had no choice but to reject me—at the time. But my eyes are corrected to 20/20 and I am completely cured of T.B., probably more sound in that respect than a goodly percentage now on duty who never knew they had it. Sure, I've got scars in my lungs, but what are scars?

* * *

My feelings toward the Japs could be described as a cold fury. I not only want them to be defeated, I want them to be smashed. I want them to be punished at least a hundredfold, their cities burned, their industries smashed, their fleet destroyed, and finally, their sovereignty taken away from them. We have been forced into a course of imperialism. So let it be. Germany and Japan are not safe to have around; we are bigger and tougher than they are, I sincerely believe. Let's rule them. We did not want it that way—but if somebody has to be boss, I want it to be us. Disarm them and

don't turn them loose.

We can treat the individual persons decently in an economic sense, but take away their sovereignty.

(27)

December 16, 1941: Robert A. Heinlein to John W. Campbell, Jr.

So far, I have not been able to peddle my valuable services. The letter in which I volunteered, accompanied by a certified copy of my physical exam report, is wending its way through the circuitous official channels. I stuck airmail postage with it with a memo to the Commandant's aide asking him to use same, and the letter asks for dispatch orders; nevertheless, it would not surprise me to be sitting here until January or so. In the meantime, I have been circulating around the offices of local naval activities, trying to find someone who wants me bad enough to send a dispatch asking for me. No luck so far. Damn it—I should have volunteered six months ago.

December 21, 1941: Robert A. Heinlein to John W. Campbell, Jr.

I was interested in your father's comment in re the navy, and in your further comments. Some of the comments he found fault with are real faults, some as you pointed out derive from a lack of knowledge of the true problems. Some of the real faults seem to me to be inherent in the nature of military organization and inescapable. The navy is an involved profession; it takes twenty-five years or so to make an admiral—and older men are not quite as mentally flexible as younger men. I see no easy way to avoid that. Is your father as receptive to new ideas as you are? Will he step down and let you tell him how to run AT&T? Is there any way of avoiding the dilemma? Nevertheless, the brasshats are not quite as opposed to new ideas as the news commentators would have us think. The present method of antiaircraft fire was invented by an ensign. Admiral King encouraged a warrant officer and myself to try to invent a new type of bomb (Note: We weren't successful.) You may remember that one of my story gags was picked up by a junior officer and made standard practice in the fleet before the next issue hit the stands. Nevertheless, there is something about military life which makes men conservative. I don't know how to beat it. Roosevelt has beaten it from the top to a certain extent by insisting on young men and/or men whose abilities he knew, but it is sheer luck that we have a president who has known the navy's problem and personnel since he was a young man. I know of no general solution.

* * *

I may get sea orders any day—along with a lot of other old crocks who would not have to go to sea if it had not been for that partisan opposition I spoke of . . .

. . . Some of Hamilton Felix's point of veiw is autobiographical. [Hamilton Felix was the protagonist of "Beyond This Horizon."] I would like to have been a synthesist, but I am acutely aware that many of my characteristics are second-rate. I haven't quite got the memory, nor the integrating ability, nor the physical strength, nor the strength of character to do the job. I am not depressed about it, but I know my own shortcomings. I am sufficiently brilliant and sufficiently imaginative to realize acutely just how superficial my acquaintance with the world is and to know that I have not the health, ambition, nor years remaining to me to accomplish what I would like to accomplish. Don't discount this as false modesty . . .

I have just sufficient touch of genius to know that I am not a proper genius—and I am not much interested in second prize. In the meantime, I expect to have quite a lot of fun and do somewhat less constructive work than I might, if I tried as hard as I could. That last is not quite correct. I simply don't have the ambition to try as hard as I might, nor quite the health. But I do have fun!

* * *

In re mental-ostrichism and boycotting the war news: A long time ago I learned that it was necessary to my own mental health to insulate myself emotionally from everything I could not help and to restrict my worrying to things I could help. But wars have a tremendous emotional impact and I have a one-track mind. In 1939 and 1940 I deliberately took the war news about a month late, via Time magazine, in order to dilute the emotional impact. Otherwise I would not have been able to concentrate on fiction writing at all. Emotional detachment is rather hard for me to achieve, so I cultivate it by various dodges whenever the situation is one over which I have no control.

(32)

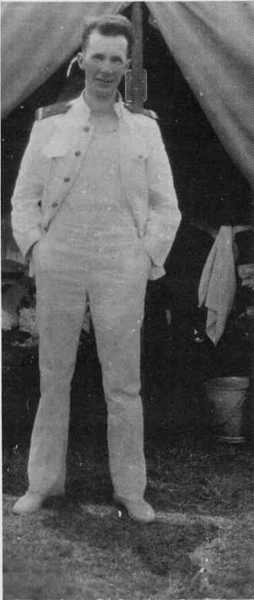

Heinlein in his white naval uniform, (early 1930s)

(32)

Heinlein's Fencing Champion medal.

January 4, 1942: Robert A. Heinlein to John W. Campbell, Jr.

You suggest that my thinking about the navy I keep compartmented away from my thinking on other subjects. It is true that I have been oriented and indoctrinated by a naval education and naval experience. It is true that a man cannot escape his background—the best he can do is to try to evaluate it and discount it. But as to your "proof"(by, God save us, Aristotelian logic!) that I keep my mind compartmented—well, much more about that later; much, much more.

In the meantime, I shall "sound general quarters and return your fire." For a long time I have from time to time felt exasperated with you that you should be so able so completely to insulate your thinking in nonscientific fields from your excellent command of the scientific method in science fields. So far as I have observed you, you would no more think of going off half-cocked, with insufficient and unverified data, with respect to a matter of science than you would stroll down Broadway in your underwear. But when it comes to matters outside your specialties you are consistently and brilliantly stupid. You come out with some of the goddamndest flat-footed opinions with respect to matters which you haven't studied and have had no experience, basing your opinions on casual gossip, newspaper stories, unrelated individual data out of matrix, armchair extrapolation, and plain misinformation—nsuspected because you haven't attempted to verify it.

Of course, most people hold uncritical opinions in much the same fashion—my milkman, for example. (In his opinion, the navy can do no wrong!) But I don't expect such sloppy mental processes from you. Damn it! You've had the advantage of a rigorous training in scientific methodology. Why don't you apply it to everyday life? The scientific method will not enable you to hold exact opinions on matters in which you lack sufficient data, but it can keep you from being certain of your opinions and make you aware of the value of your data, and to reserve your judgment until you have amplified your data.

All I said with reference to the Pearl Harbor debacle was that the necessary data for an opinion was not yet in and that we should reserve judgment until the data was available. I added, in effect, that this was no time for the intelligent minority to be adding to the flood of rumors and armchair opinions flying through the country. I still say so. As an intelligent and educated man, you have a responsibility to your less gifted fellow citizens to be a steady and morale-building influence at this time. Your letters do not indicate that you are being such.

I am going to try to take up a number of points one at a time, some from your letters, some from related matters.

"Aid and comfort to the enemy, phui. Morale damage, hell." (From your letter) I am going to have to be rather directly personal about this. It may not have occurred to you that I am a member of the armed forces of the United States at the present moment awaiting orders, for sea duty I hope. Such comments as you have made to me might very well damage the morale of a member of the armed forces by shaking his confidence in his superior officers. There happens to be a federal law forbidding any talk in wartime to a member of the armed forces which

might tend

to destroy morale in just that fashion—a law passed by Congress, and not just a departmental regulation. It so happens that I am sufficiently hardheaded, tough-minded, and conceited not to be much influenced by your opinions of the high command. I think I know more about the high command than you do. Nevertheless, you were not entitled to take the chance of shaking my confidence, my willingness to fight. And you should guard your talk in the future. It might, firsthand, secondhand, or thirdhand, influence some enlisted man who had not the armoring to his morale that years of indoctrination gives me.